THE FILM AS FAIRY TALE — DEVELOPMENTAL ISSUES RAISED BY THE WIZARD OF OZ

Children love this film because it touches on important questions, fears, and desires. These are core developmental issues that children must work out for themselves. The popularity of the story is due to the fact that these issues intrigue young people and resonate with the child inside us all.

They include, not in any order of priority, the following:

- Home is the center of a child’s life. But children know that somewhere beyond the safety of home there is a world that is exciting and colorful, yet sometimes dangerous. What will happen if the child must leave home before he or she has grown up? Will the child be able to meet the challenges? Will he or she ever be able to find the way back home?

- What about relationships with grownups? Adults are all-powerful to a young child but a child soon learns that this power has limits, as when Auntie Em and Uncle Henry couldn’t prevent Miss Gulch from taking Toto.

- What do children do when adults ignore or cannot respond to their pleas for help?

- How does a child learn what he or she needs to know to get through tough situations?

- Can children ever triumph over evil adults?

- What about appearances? How do you tell appearance from reality?

- What is the nature of power? How do people get power over others?

- How does a child meet the challenges of becoming an adult? Specifically, how do you act intelligently (the challenge faced by the Scarecrow); how do you act courageously when you are very scared (the goal for the Cowardly Lion); and how can you be a caring individual (the desire of the Tin Man?

“The Wizard of Oz” also contains some important moral lessons and opportunities for social-emotional learning. See Suggested Responses to Discussion Questions 4 – 6**** in the Learning Guide.

Through this story, we also see that if we want to go looking for greater purpose in our lives, we may want to avoid traveling “somewhere over the rainbow,” and look instead in our own home community. For some of us, “there’s no place like home,” no matter what wonders and adventures might await us in the big, colorful world. “The Wizard of Oz” and “It’s a Wonderful Life” are the major cinematic proponents of this view. There are many other movies that glorify the effort of young people to break out of the restrictions of their home environments and live in that brightly colored, exciting, and somewhat dangerous world beyond their home. Some of these movies can be found in the Breaking Out section of the Social-Emotional Learning Index.

THE MOVIE AS A WORK OF LITERATURE

The movie employs the device of a frame story. Events in Kansas, shown in black and white, come at the beginning and at the end of the film. They bracket and give meaning to the colorful, adventurous journey through Oz. The characters and occurrences in Kansas parallel and foreshadow the characters and occurrences in the main story. Dorothy’s dream transformed the three farmhands into the Scarecrow, the Cowardly Lion, and the Tin Man. It made Miss Gulch into the Wicked Witch of the West and Professor Marvel into the Wizard of Oz. When Toto bites Miss Gulch, the advice given by the farmhands foreshadows the personality of their parallel characters in Oz. The conflict with Miss Gulch foreshadows and is converted into the conflict with the Wicked Witches. The powerlessness of Auntie Em and Uncle Henry foreshadows the powerlessness of the Wizard to defeat the Wicked Witch of the West.

Irony plays an important role in the story. It is Dorothy, the innocent child who vanquishes the powerful Wicked Witches who terrorize Oz. It is Toto, the meekest creature of them all who exposes Oz, “the great and powerful.” It is the charlatan Wizard who gives legitimacy to the Scarecrow’s intelligence, the Tin Man’s caring, and the Cowardly Lion’s courage. Oz “the great and powerful” is really a somewhat pathetic old man who doesn’t even know how to work the baloon that he sails off in.

There are many symbols in the movie. Here are a few: the ruby slippers stand for the self-knowledge required to find happiness; the tornado is a symbol for the strong emotions felt by Dorothy when Auntie Em and Uncle Henry could not stop Miss Gulch from taking Toto (the storm abates with the death of one of the Witches).

ALLEGORY TO THE HISTORY OF POPULISM IN THE U.S. — LATE 1800S

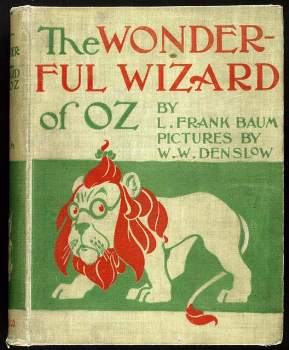

Educators have used the book, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, as an allegory for the history of the populist movement in U.S. politics in the late 1800s. The validity of the theory is disputed. See the Links to the Internet for sites reflecting the conflicting interpretations and The Annotated Wizard of Oz, Centennial Edition, Introduction, pages lxxxix and xc. Whether the theory is correct or not, it is an excellent way to teach: (1) the literary device of allegory and (2) the history of populism in the U.S. during the late 1800s.

A simplified analysis is that the populists championed a bimetal standard for the U.S. currency, i.e., one based on both gold and silver. With a gold standard, there was too little paper money in circulation. The bankers and industrialists of the day controlled gold and wanted a gold-based currency. This restricted the availability of money and hence, so the theory went, kept inflation and prices low. The populists believed that if a bimetal standard was adopted there would be more paper money and an increase in commerce, salaries, and prices benefitting farmers and workers.

The Quantity Theory of Money can be expressed as: MV = PQ where:

M = the quantity of money in circulation (M1).

V = the velocity with which money circulates in the economy. (This can be assumed to be a constant. It does go up slowly over time as the technology for clearing transactions through the banking system is improved.)

P = the average price level.

Q = real national output (GNP or GDP).

The Quantity of Money Theory of Price is a corollary to the Quantity Theory of Money and asserts that: P = MV/Q. This theory means that when the amount of money in circulation (M) rises, the average price level (P) will also rise.

The U.S. had been on the gold standard (i.e., all dollars issued had to be backed by gold and could be redeemed for gold) until the Civil War. After the Civil War, the issuance of currency was restricted and, in 1879, the gold standard was resumed. The U.S. economy throughout most of the late 1800s was expanding rapidly and there was a need for more currency. The 1890 Sherman Silver Purchase Act provided for increased purchase and coinage of silver. There were fears that the U.S. would switch from a gold to a silver standard and people began to hoard gold, depleting the Treasury’s supply. The populists believed that more money (M) would result in an increased average price level. This was to be accomplished through “bimetalism,” adding silver as a second metal on which the dollar was based.

The populists never came to power in the U.S. The most influential populist/bimetallist candidate for president was William Jennings Bryan. Nominated for president by the Democratic party on three occasions, Bryan never achieved the presidency, despite the fact that on one occasion he won the popular vote.

An allegory is “the representation of spiritual, moral, or other abstract meanings through the actions of fictional characters that serve as symbols.” Random House Webster’s College Dictionary, 1999. The analogies on which this allegorical interpretation is based (there are some variations among educators) are as follows:

Dorothy = the American people: plucky, good-natured, naive.

Toto = the Prohibition (Temperance) party. Prohibitionists favored the bimetallic standard but like any fringe group often pulled in the wrong direction. So they got to be a dog. (Toto is a play on “teetotalers.”)

Oz = the almighty ounce (oz) of gold.

The yellow brick road = a path paved with gold bricks that leads nowhere.

Dorothy’s silver slippers = originally the property of the Wicked Witch of the East, until Dorothy drops the house on the Witch. Walking on the yellow brick road with the silver slippers represented the bimetallic standard. (MGM changed the silver slippers to the ruby slippers to exploit the technology of Technicolor.)

The Good Witch of the North = New England, a populist stronghold.

The Good Witch of the South = the South, another populist stronghold.

The Wicked Witch of the East = Eastern banking and industrial interests. She is killed by Dorothy’s falling house because the populists expected that the Eastern industrial workers would vote populist, but this never really happened.

The Wicked Witch of the West = the West was where the populists were strongest. The only reason the West gets a Wicked Witch is: a) you need two bad guys to balance the two good guys, and especially, b) William McKinley was from Ohio, then thought of as a Western state. The Wicked Witch is sometimes identified directly with President McKinley.

The Munchkins = slaves of the Eastern banking and industrial interests, i.e., Eastern workers who didn’t vote for Bryan.

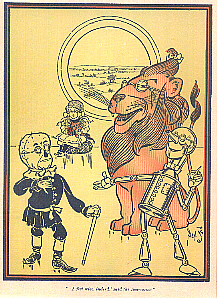

The Scarecrow = Western farmers. They were populists.

The Tin Man = Eastern workers. Populist mythology always looked to this group for support, but never found it in reality. Baum realized this (most populists didn’t) and shows the Tin Man as a victim of mechanization. He’s so dehumanized he doesn’t have a heart.

The Cowardly Lion = William Jennings Bryan.

The Emerald City = Washington, D.C. The color is suggestive of paper greenbacks.

The Wizard = President McKinley, but sometimes his advisor, Marcus Alonzo Hanna. McKinley and Hanna deceived the people. The Wizard promises Dorothy that he will be able to bring her back to Kansas with a balloon filled with a lot of “hot air.” Instead, it is the slippers, which Dorothy had all the time, that took her home. The Wizard’s gifts of courage, brains, and a heart are deceptions, although beneficial ones. Much of this section is quoted or derived from The Wizard of Oz as a Monetary Allegory by Robert F. Mulligan, Ph.D., Western Carolina University College of Business.