Before Showing the Film:

Consider distributing and having students review, TWM’s Movie Worksheet for 12 Years a Slave. Modify the worksheet as appropriate.

Information Helpful to Students:

Relate the following information to students to give them a better understanding of the movie.

The terms “paddy” and “pattyrollers” or “paddy rollers” were names given by slaves to patrols of whites who were paid to be on the lookout for fugitive slaves and to hunt down runaways. Paddy’s were armed and often brutal.

The culture of the people living in what is now the U.S. has been a slave culture or has tolerated slavery from 1619 when the first slaves were brought to Jamestown, Virginia until 1865. That is a period of 245 years, almost a century longer than the period since slavery has been abolished. Slavery was so intertwined with the culture of the American South that it took the bloodiest war in U.S. history to make it illegal. Even then substantial portions of the slave society survived for another hundred years in Jim Crow laws and customs. The country is still not completely free of the racism that aided and abetted slavery.

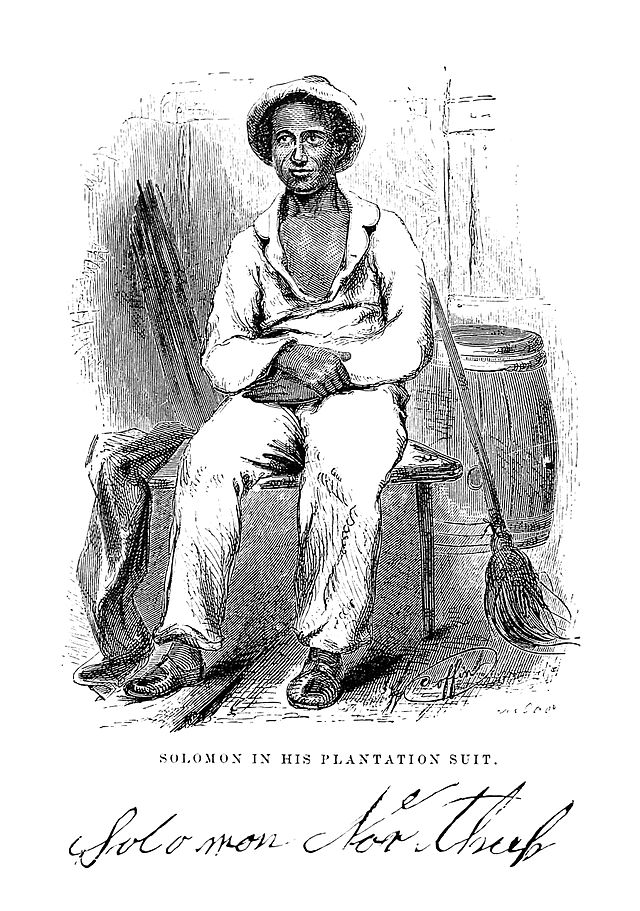

Solomon Northup’s book Twelve Years a Slave is one of the most important examples of a genre of American literature called the slave narrative. In fact, African-American literature in the U.S. begins with the slave narrative, most of which were told to white abolitionist ghost writers after slave had escaped from the South. Solomon Northup’s Twelve Years a Slave became a best-seller in 1853 and then a major motion picture 160 years later.

Test Your Historical Instincts Exercise:

Tell students the following: (1) It’s time to test your historical instincts. (2) The movie is reasonably historically accurate except for a few scenes. (3) As you watch the film, look for these scenes. After watching the movie, there will be a class discussion in which you may be asked to identify an inaccurate scene or set of scenes.

Note to Teachers: The heart of this exercise is the discussion after the film. Teachers can prepare for this discussion in about five minutes by reviewing the highlighted sections of TWM’s Essay on Historical Accuracy.

As an alternative to class discussion, students can be asked to write a paragraph on a scene or a set of scenes that their instinct tells them are inaccurate and why. The paragraphs will be graded only on the quality of the writing.

After Showing the Movie:

Complete the Test Your Historical Instincts Exercise:

Suggested Responses:

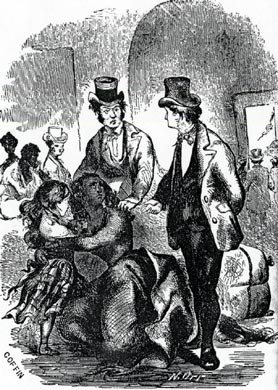

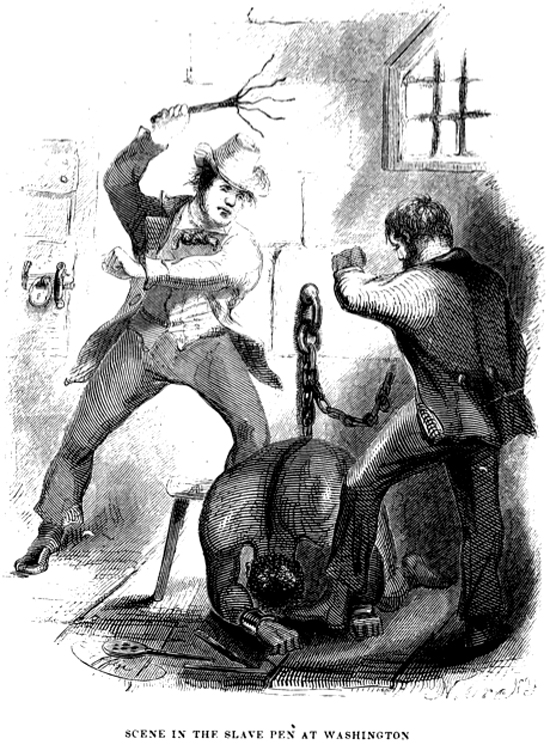

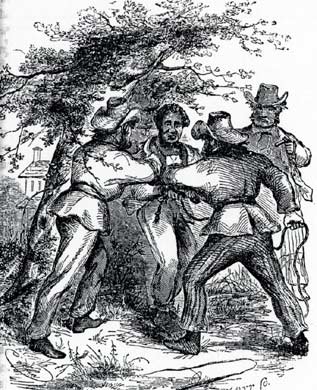

There are three substantial inaccuracies in the film: (a) the set of scenes before the kidnapping showing Northup as a prosperous individual fully accepted by white society; (b) the scene in which a lone sailor comes into the hold of the Orleans to take Eliza up to the deck and then knifes a slave who tries to protect her; and (c) Mistress Shaw giving Patsey tea.

There are no specifically correct answers to the questions about why the filmmakers chose to include these obviously incorrect scenes. A good discussion will raise the following issues.

As to the first scenes of the wealth and acceptance of Solomon Northup, one possible explanation is that the people who made the movie wanted to draw a contrast between the life that free blacks lived in the North and the life they lived as slaves in the South. A second possible reason is that the filmmakers didn’t want to alienate their audience by showing that blacks were discriminated against in the North before the Civil War and did not have equal rights. Another possibility is that the filmmakers wanted generally affluent filmgoers to be able to identify with the character of Solomon Northup. Whatever the reason, the filmmakers vastly underestimated their audience. Scenes showing Northup having a poor and struggling but intact family in New York would have been more accurate historically and also true to the tale told in Northup’s slave narrative. Properly presented, it would still have provided a stark contrast to Northup’s life as a slave in which families were routinely broken up and family values were routinely ignored by most slave masters.

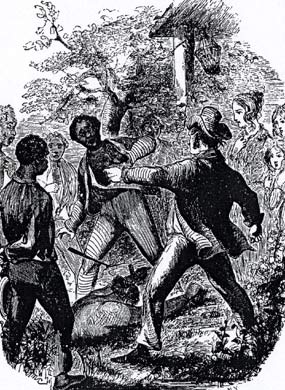

On the trip, the New Orleans the movie shows the slave being stabbed to death by a sailor when the slave tries to protect Eliza from being taken up to the deck, presumably for sex. This scene didn’t occur. A slave did die on board the ship, but he died from smallpox. The historical record was altered and this incident was added because it’s very dramatic for Robert to be murdered while trying to protect Eliza. However, in 1841 a healthy male slave was worth $650 (estimated to be about $18,000 in 2014 dollars using an adaptation of the Consumer Price Index. It is unlikely that a sailor would so quickly kill such a valuable piece of property. In addition, it is unlikely that a sailor would have gone alone into the hold of a ship containing a number of unchained male slaves.

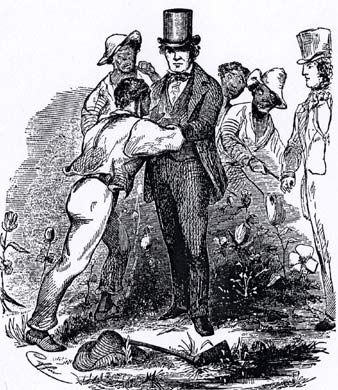

The scenes of the black Mistress Shaw taking tea with Patsey could have been placed in the film to show that there were a very few slaveholders who honored their slave concubines and freed them or their children. The scene is played “tongue-in-cheek” and could have been placed in the film solely for comic relief.

Additional Information for Students

Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the novel by Harriet Beecher Stowe, was published in 1852, a year before Northup’s Twelve Years a Slave. The novel was one of the most popular books ever published and historians say that it was an important factor in turning the North against any expansion of slavery into the Western Territories. Twelve Years a Slave was published the next year and confirmed the indictment of slavery contained in Stowe’s novel. The connection between the two books was not lost on the Northern Press. Eakin, pp. 262 – 265.

Twelve Years a Slave was ghostwritten for Northup by David Wilson, a lawyer/author. Wilson wrote the book and had it published in a period of three months. a very short period of time. He was spurred on by attorney Henry Northup, the family friend who went to Louisiana to free Solomon. Attorney Northup “figured that information from the forthcoming book would reach readers who could and would identify the kidnappers. Attorney Northup was correct.” Eakin p. 263 at note 3. While the kidnapers were found and prosecuted, they were not convicted because the proceedings were delayed by appeals and before the case could come to trial, Solomon Northup had disappeared again, this time for good. No one knows what happened to him or how he died.

People are still kidnapped and sold into slavery all over the world. Most current-day slavery in the U.S. is sexual slavery in which girls and young women are forced to be prostitutes.

Grave Suspicions about the Death of Solomon Northup: After he returned to freedom, Northup gave lectures to spur sales of his book, assisted in the Underground Railroad, and addressed abolitionist rallies.

He also pursued the criminal prosecution of the kidnappers who claimed that they hadn’t kidnapped Northup at all, but that it was a scheme that he had participated in to cheat Burch out of the money he paid to the kidnappers. They claimed to have done this before with a free black man from the North. Northup steadfastly denied this charge. Eakin pp. 215 & 216.

The criminal prosecution of the kidnappers ended when, after many years of delays in the Court proceedings, Northup disappeared and the case was dropped. Eakin pp. 210 – 214. Many who knew Solomon Northup believed that he was murdered by his kidnappers or kidnapped again and sold into slavery a second time.

The following is from the ending of Dr. Eakin’s study of Solomon Northup’s life at pages 217 & 217:

John Henry Northup, born in Sandy Hill [New York] in 1822, a nephew of Henry Northup, was well acquainted with both Solomon and Henry Northup. [He would have been 19 at the time of the kidnapping and 31 when Solomon Northup returned to New York.] He wrote his version of the story in 1909 in a letter to his cousin . . . who recounted it:

John Henry Northup said not long after they came home, Henry B. “got a lawyer to hear Sol’s story. Soon by questions he got enough to write a book.” According to John Henry, Solomon Northup: 12 Years in Slavery, written quickly and published in 1853, “created a sensation for it came out a short time after Uncle Tom’s Cabin . . . by Mrs. Stowe. The last I heard of him,” said John Henry in 1909, Sol “was lecturing in Boston to help sell his book . . . All at once said John Henry, “he disappeared . . . We believed that he was kidnapped and taken away or killed or both.”

Additional Curriculum Materials:

Teachers may want to provide students with the following handouts prepared by TWM. (1) The Slave Narrative as Literature and (2) Slavery: A World-Wide View, Then and Now (placing American slavery into a global and historical context). As to the latter TWM has prepared a homework assignment to test comprehension of the materials in the essay.

Turning Students Toward the Written Slave Narratives:

After students have seen the movie, turn their minds back to the written slave narratives by having them read all or a portion of Northup’s Twelve years a Slave (see assignments 1, 3 & 4 below) or by having them read all or a portion or another slave narrative, such as Frederick Douglass’ The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, Written by Himself. Set out below are several excerpts and one abridgment of slave narratives prepared by TWM for shorter student reading assignments.

- Chapters I – III of The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, The African, Written by Himself;

- Short excerpt from The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, Written by Himself describing Mr. Douglass’ decision to learn to read at whatever cost;

- Booker T. Washington’s Up from Slavery chapters I – VI describing his experiences as a boy during slavery and just after Emancipation;

- Sojourner Truth’s speech “Ain’t I A Woman?” delivered in 1851 at the Women’s Convention in Akron, Ohio; the link is to a web page setting out the best version of the speech in the vernacular and also a translation to standard English;

- Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Written by Herself by Harriet Jacobs; (TWM has prepared a six-page handout intended to capture the imagination of students and interest them in reading Ms. Jacobs’ narrative (this document alone will convey many of the lessons contained in Ms. Jacobs’ narrative); for teachers who don’t want to assign the entire book, TWM has abridged this work and cut it to about 1/3rd its original size; see TWM’s Abridged Version of “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Written by Herself”).