See Learning Guide to Sarafina.

Racial tensions in South Africa date back at least to the eighteenth century when Dutch settlers expanding inland from the coast met Xhosa tribes expanding to the south and west. Though defeated militarily by the British in 1902, the Boers (descendants of Dutch, French and German colonists) gained the upper hand in 1910, when the Union of South Africa was formed. Almost immediately, the new government began to restrict the rights of blacks and persons of Indian or mixed descent. In 1948 the South African government adopted apartheid policies which excluded the black majority from nearly all facets of political, economic and social life. Africans were relegated to impoverished “homelands”. When blacks began to resist apartheid, beginning in the late 1950s, the South African government responded with repressive police state tactics.

Confrontation prompted the Sharpeville Massacre in 1960, where police killed 69 unarmed demonstrators. A series of international sanctions were imposed on South Africa that year; measures were toughened in subsequent years.

The setting for the story shown by this film occurred in 1974 when the South African Minister of Bantu Education and Development, P.W. Botha, declared that Afrikaans would be the language of instruction in black schools. A government official was quoted as saying ” …an African might find that the ‘big boss’ only spoke Afrikaans or English and it would be to his advantage to know both languages.” Black high school students in Soweto responded on June 16, 1976 with a series of clashes with police and military units. As depicted in the movie, security forces killed 150 in the first week, with nearly 700 perishing before the year was out. Leaders such as Stephen Biko died, producing a military arms embargo by the international community upon the South African military.

In 1989 President P.W. Botha resigned as the leader of the National Party (the ruling party) due to illness. His successor, F.W. de Klerk, after negotiating with the African National Congress, released many political prisoners, including Nelson Mandela (who had been imprisoned since 1963) in 1990. (At one pont, Botha, now recovered, tried to return to power to reverse the reforms, but de Klerk prevented this.) De Klerk repealed pro-apartheid policies such as the Group Areas Act, the Land Act, and the Population Registration Act.

Whites voted to abolish apartheid in a 1991 referendum, paving the way for blacks to vote in the 1994 election. The African National Congress won 62.65 percent of the vote (but not the 66 percent necessary to empower it to draft the constitution). A Government of National Unity (GNU) was formed with the National Party, which finished second with 20.4 percent of the vote, in order to draft the constitution. Other participating parties (among the 19 on the ballot) include the Inkhata and the Pan-Africanist Congress (PAC). Nelson Mandela was chosen as President by the legislature, while de Klerk and Thabo Mbeki were named Deputy Presidents. The peaceful transition of power from the white minority to the black majority is one of the most remarkable acts of political courage and restraint (on both sides) in the history of mankind.

The new constitution produced a Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) which would promote national unity and reconciliation by hearing cases of human rights abuses during the apartheid era. Led by Archbishop Desmond Tutu, the TRC heard more than 20,000 statements in their investigations. A report was delivered to the government in 1998.

In 1993, Mandela and de Klerk were jointly awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for “their work for the peaceful termination of the apartheid regime, and for laying the foundations for a new democratic South Africa.” The Nobel Committee stated that:

From their different points of departure, Mandela and de Klerk have reached agreement on the principles for a transition to a new political order based on the tenet of one man, one vote. By looking ahead to South African reconciliation instead of back at the deep wounds of the past, they have shown personal integrity and great political courage.

Ethnic disparities cause the bitterest conflicts. South Africa has been the symbol of racially conditioned suppression. Mandela’s and de Klerk’s constructive policy of peace and reconciliation also points the way to the peaceful resolution of similar deep-rooted conflicts elsewhere in the world.

The previous Nobel Laureates Albert Lutuli and Desmond Tutu made important contributions to progress towards racial equality in South Africa. Mandela and de Klerk have taken the process a major step further. The Nobel Peace Prize for 1993 is awarded in recognition of their efforts and as a pledge of support for the forces of good, in the hope that the advance towards equality and democracy will reach its goal in the very near future.

André Brink was born into a South African Dutch family. He insisted on confronting the social and political realities of his country. He moved to Europe for a time but later returned to South Africa to “accept full responsibility for everything I write — not as a writer for a small white enclave, but as a writer belonging more to Africa than to Europe.” Mr. Brink has received numerous awards, including three CNA Awards, South Africa’s most prestigious literary prize, and Britain’s Martin Luther King Memorial Prize. France has made him a Chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur. His work has been published in twenty countries.

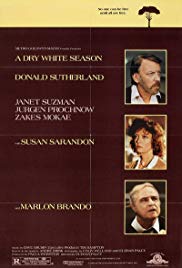

Two of Mr. Brink’s novels, A Dry White Season and Looking on Darkness were banned by the South African government. While the script of the movie departs from the book in many specifics, the film retains the thrust of the story, a story written by an Afrikaaner telling an authentic tale from his own tortured community.