BIZET’S DREAM

SUBJECTS — Biography; Music/Opera; World/France;

SOCIAL-EMOTIONAL LEARNING — Father/Daughter; Talent;

MORAL-ETHICAL EMPHASIS — Responsibility.

AGE: 9 – 12; No MPAA Rating;

Drama; 1995; 53 minutes; Color.

There is NO AI content on this website. All content on TeachWithMovies.org has been written by human beings.

SUBJECTS — Biography; Music/Opera; World/France;

SOCIAL-EMOTIONAL LEARNING — Father/Daughter; Talent;

MORAL-ETHICAL EMPHASIS — Responsibility.

AGE: 9 – 12; No MPAA Rating;

Drama; 1995; 53 minutes; Color.

Michelle, a twelve-year-old girl living with her mother in Paris, is taking piano lessons from Georges Bizet. He is preoccupied with the effort to compose the opera Carmen. Events in Michelle’s life and in Bizet’s have parallels in the plot of the great opera. The girl’s father is a French soldier stationed in Seville. She and her mother have not seen him in a long time. Don Jose, the primary male character in the opera, is also a French soldier stationed in Seville. He falls in love with Carmen, an attractive gypsy girl, and abandons his fiancé. Michelle becomes afraid that her father has run away with someone like Carmen and will never come home. It also appears that Bizet’s wife was seeing other men and was not faithful to him. The movie implies that some of Bizet’s feelings about his wife’s behavior inspired the plot of the opera.

Selected Awards: This film is a part of the Composers’ Specials. The series received the 1996 CableACE Award for Best Children’s Series and was a Gemini Award Winner (Canada’s Emmy) for Best Youth Program or Series. The series also received the American Library Association’s Recommendation to all public schools and libraries in 1996. “Bizet’s Dream” itself won the following awards and nominations: The Alliance for Children and Television Award of Excellence; the Video Magic Award – Parenting Magazine’s selection as Best Children’s Video of the Year; and the KIDS FIRST Award for Best Children’s Video from The Coalition for Quality Children’s Video.

Featured Actors: Maurice Godin, Brittany Madgett, R.H. Thompson, Catharine Barroll, Yseult Lendvai, Vlastimil Harapes, Sally Cahill, Jackie Harris and Joan Heney.

Director: David Levine.

This film features the music of Carmen. Children will become absorbed in the plot to find out if Michelle’s father has run away with a beautiful gypsy. The film will give a child some background about the opera and an introduction to Bizet and his music.

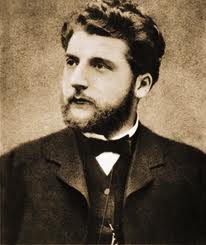

Georges Bizet (1838 – 1875) was a French composer known for his operas, chiefly Carmen. Bizet’s operatic work influenced the “verisimo” style which tried to make operas more realistic. See Learning Guide to Carmen.

In fact, there was a 12-year-old girl living in Paris who was one of Bizet’s three piano students during the time that he was composing Carmen. She was an American, and her description of Bizet is remarkably similar to the description of Bizet provided by this film. Her experiences with Bizet are recounted in Paris Days and Evenings by Stuart Henry, J.B. Lippincott Company, 1896, pages 191 – 202. You might want to read this section aloud to younger children or have older children read it themselves. Then see the film again and talk about the similarities:

At first he used to come to our place. … He was supposed to come at three o’clock. You never saw a more irregular man. We would wait, wait, wait; and I was always glad if I thought he was not coming, for I was afraid of him, and naturally dreaded the severe lessons. Not that he ever scolded, but the way he would look at you through those eyeglasses!

And of all the absentminded persons! He was not conscious of time, place, anybody, or anything but music and petits fours [small cakes] at four o’clock. He was always dreaming; up in the clouds-loin [far away]. He would usually go away and leave something in the room — often left on the piano the banknotes that Mamma had paid him; always forgot his overcoat on the rack in the hall, and once in a while the maid would run after him with his hat. He did not appear to relish the idea of receiving pay; apparently disliked to handle money or think of it; treated my lessons as if they were a favour to us. Yes, an ideal artist to the tip of his fingers to the ends of his hair; hating the material, prosaic world; always keyed up to the last notch in a realm of his own. He never seemed to realize that I existed in flesh and blood; scarcely ever looked at me or touched me; could not have told whether I was blonde or dark. I was merely a sort of concept taking a music lesson! He was as economical of his compliments… always left me feeling that no one could be doing more wretchedly; that I was utterly stupid, hopeless: Once in a great while, though he would say: “Pas mal, pas trop mal,” [Not bad, not too bad] and then I felt elated.

He was as uneasy as a lion in a cage during the lesson; moved about the room, sitting down and getting right up again, looking everywhere but at the piano. I often thought he was paying no attention to my playing, and sometimes I would begin to grow careless, and make little slips in fingering, and then he would say savagely: “Je ne dors pas! Je ne dors pas!” [I’m not sleeping! I’m not sleeping!] It has been a marvel to me to this day how he could detect the slightest error in fingering, and be looking at a picture on the other side of the room. He never touched my piano, never played a lesson through for me at our house; said that he did not want to make apes of his pupils.

Brimful of music, bubbling over with it, as he was every moment, I do not remember that he ever whistled a note, but he hummed. He had no voice- no, not a bit of voice; said that if he had one, he would have been a great singer. He hummed, always getting tremendously excited when the music became triumphant. When I would come to the crowning passage in Chopin’s “Second Scherzo,” he would become half mad. He would rush up an down the room crying out to me: “This is the climax! Throw your whole soul into it! Don’t miss a note! Play as if you were saying something!”

Oh, but I haven’t told you how handsome he was. He was very plump and vigorous- a very showy, attractive man, without ever thinking that he was, or seeming to care what his effect was on other people. He had light brown hair, and a full beard almost russet or reddish-brown. His eyes were dark gray or dark blue. He dressed with extreme care and for his own personal satisfaction. It was one expression of his thoroughly artistic nature, and seemed to him as natural a need as any other. There was not a hint of a dandy about him. He did not act as if he were conscious that any one was to look at him.

He wore the finest linen I ever saw. His gloves were gants de suede [suede] — ladies gloves — very long, soft, light brown, with no buttons. And when he would come in and strip off his gloves, throw them on the piano, and reveal those beautiful hands! They were hands of shell — the palms all shelvy, with pearly layers of flesh and bluish traceries between. They were chubby, white, soft- not large; he always said one must have large hands for the piano. He seemed proud of them, and careful as a rule to keep them covered up — gloved. He had a lovely complexion — pink and white. But with all his dreaminess — his nonchalant, artistic temperament — he did not impress one at all as being an ethereal person. He was too healthy, too thoroughly rammed with life, for that.

And what a gourmand [glutton] for sweets! He was crazy for bonbons, cakes, friandises [sweets]. He always had petits fours [little cakes] at four o’clock. He was everywhere and at all times stuffing himself with confectionery. As soon as he saw the bonbon dish at our house, he would make for it and eat what there was in it. He once nearly lost his life when indulging his sweet tooth. There used to be a patisserie [pastry shop] — very likely it’s there yet — on the corner of the boulevard right across from the old Opera-Comique — Place Boieldieu. M. Bizet was there one day when the ceiling suddenly fell in, or a part of it. I think one or two persons were killed. He barely escaped, for a great piece of the plaster struck him on the shoulder, just missing his head.

After about a year, M. Bizet said one day: “I am too busy to be giving lessons. If you are to keep on, you will have to come chez moi [my house] hereafter.” And so I went regularly to his apartment in the Rue Saint Georges. M. Bizet did not appear to have money, but Madame Bizet had. … Their apartment was on the third floor — very artistic, with pictures and bronzes. I remember particularly the heavy portieres [curtains] with deep fringes.

At home M. Bizet seemed a different man. When he was chez nous [at our house], he was ill at ease — gene– [bothered] evidently annoyed, displeased at the thought of giving lessons, so he rarely stayed longer than the half-hour. Chez lui [at his house] he seemed glad to see us, and wanted to visit, especially when Mamma happened to go with us. He would frequently be half the afternoon giving me my half-hour. He talked, showed his pictures, and would bring in his beautiful baby. He was very proud of it. Madame Bizet would almost always come in, and altogether it was very hospitable — neighbourly.

Here he was interested, enthusiastic — seemed to have a wealth of leisure, and made us feel as if no one was in a hurry or had anything important to do; and still he worked to excess as everyone knew. Here we discovered, too, how he loved to play the piano. He would play this and that piece, and was apparently very fond of matching his hands against the old, white ivory of the key-board. He was a pianist of the highest order — superb and brilliant, full of sentiment — entrain, fire — spontaneous, colourful, yet having all the technique and precision of the Conservatoire.

… Sometimes he would excuse himself during the lesson, and go in to the piano in the studio, close the door, and work over some strain that would be running in his head. This proved to be “Carmen.” He was full of the airs of “Carmen” at this time, so I heard most of them sooner than almost anyone, but of course I did not know what they were. We only knew he was at work on an opera. He would hum the melodies and develop them on the piano. I recall particularly the toreador song ….

Oh, how he threw his soul into all these strains! Yet he did not appear to harbour any illusions about the fate of the opera, for one day some one asked him, “Well, do you think your new opera is going to be a success?” “Grand Dieu, no!” [Great God, no!] replied M. Bizet, with an impatience which revealed the deep undercurrent of sadness and disappointment within him; “it will fall flat like the others,” or words to that effect. He was really a sad man in spite of all his vigour, robustness, and love of music. He had been deeply wounded by the critics and the public. He felt that people persisted in misinterpreting his art — in sacrificing him on the national altar of race prejudice. He was accused of being Wagnerian. Whether the failure of “Carmen” at the Opera-Comique hastened his death, I cannot say. It was given the third of March, and he died the third of June 1875. At any rate, he was putting his full energy into it, and giving it scrupulously the best within him. Did you know that Carmen’s chanson d’entree [entrance aria] was rewritten or remade thirteen times!

The similarities between this description and the character of Bizet as portrayed in the film are striking. It is likely that the creator of this film had read this account.

QUICK DISCUSSION TOPIC:

In fact, there was a 12-year-old girl living in Paris who was one of Bizet’s three piano students during the time that he was composing Carmen. She was an American and her description of Bizet is remarkably similar to the description of Bizet provided by this film. It is quoted in the Helpful Background Section. You might want to read this section aloud to younger children or have older children read it themselves. Then see the film again and talk about the similarities.

1. See Discussion Questions for Use With any Film that is a Work of Fiction.

2. What do you think it would be like to have a music teacher who was a famous musician?

3. Michelle, the young girl character in this film, allowed her imagination to run away with the idea that her father would be like Don Jose, come under the influence of a mysterious woman, and never return home. Is this realistic? Has your imagination ever gone wild making you afraid of something that did not come to pass? How did you deal with that situation?

Discussion Questions Relating to Ethical Issues will facilitate the use of this film to teach ethical principles and critical viewing. Additional questions are set out below.

(Do what you are supposed to do; Persevere: keep on trying!; Always do your best; Use self-control; Be self-disciplined; Think before you act — consider the consequences; Be accountable for your choices)

1. How did the young girl violate the principle of “responsibility” when she tried to take the train to Spain to see her father? Who were the stakeholders in that decision? What risks was she taking by trying to run away from home?

Last updated December 9, 2009.