After the film has been watched, engage the class in a discussion about the movie.

A Fundamental Question:

Do the dead make claims upon the living? Do the men who died at Iwo Jima make a claim on you? If so, what is that claim?

Suggested Response:

A good discussion will include the following: The dead do make a claim and that claim is to live our lives to be the best people we can be so that their sacrifice will not have been in vain. The dead cannot make a claim for vengeance because that will only result in an endless cycle of violence.

(A) The Nature of Heroism and the Difference Between Heroism and Celebrity

1. Why was it important to the three surviving flag raisers to stress that the real heroes were the young Marines who died on the battlefield?

Suggested Response:

It was a matter of honesty and loyalty. The flag raisers didn’t think that raising the flag was anything consequential, and they didn’t want to take the credit away from their buddies for sacrifices in the battle. It was a matter of loyalty to their friends in the unit and fellow Marines. Raising the flag was one of the few times that the Marines were not acting heroically during the battle of Iwo Jima.

2. Do you agree with the three surviving flag raisers that the real heroes were the young Marines who died on the battlefield? Describe your reasons.

Suggested Response:

There is no single correct response to this question. A full discussion will include the following points: (1) Any soldier who landed on Iwo Jima and was able to force himself forward into the battle was a hero. As Admiral Nimitz said, “Uncommon valor was a common virtue” among the Marines who attacked the entrenched Japanese positions on Iwo Jima. (2) There were some who distinguished themselves beyond the heroism of most Marines by taking extra chances to save their buddies or to pursue the Japanese. Those Marines were given the Medal of Honor or the Navy Cross or some other award if their efforts were observed and if the observers survived. Of the three surviving flag raisers, only John Bradley, the medic, was given a medal. There were probably many Marines who performed just as heroically as those who were awarded medals but everyone who observed their exploits died and their efforts were not recognized.

3. What is heroism?

Suggested Response:

Here is one definition: placing your life or your personal safety at risk for the benefit of a noble cause or to protect another person or persons. Heroism can also involve placing at risk or sacrificing something that you have worked many years to create.

4. It is said of soldiers that they fight for their country but they die for their friends in their unit. What is meant by this and how does it relate to heroism?

Suggested Response:

Soldiers who enlist in the armed forces in times of war and put themselves in harm’s way usually do so to protect or serve their country. However, soldiers move forward under fire because their unit is ordered to take a position. Their loyalty to their friends in the unit is usually the most important motivating factor in their decision to risk their lives. This is especially true with respect to actions of uncommon valor in which soldiers put themselves at special risk in a situation in which their actions are necessary to protect other members of their unit, such as falling on a grenade or rushing a pillbox.

5. Evaluate the heroism shown by people in these three situations: (a) an ordinary citizen who risks his or her life by dashing into a burning building to save a stranger, (b) a fireman who does the same thing, or (c) a soldier who risks his life to save the buddies in his unit. Describe your reasons.

Suggested Response:

A good discussion will including the following: (a) The ordinary citizen is extremely heroic because there is no particular duty to act nor is there any personal relationship with the person being saved; (b) the fireman also doesn’t have a personal relationship with the individual being saved; however, the fireman assumed a duty to save lives when he/she took the job although no duty was undertaken to risk his/her life to save another; the fireman may also have received some training in how to reduce risk when entering a burning building; arguments can be made that the employment and the training makes the fireman’s heroism somewhat less than that of the civilian; it is still heroism; (c) soldiers do not have a duty to sacrifice their lives for the other soldiers in the unit, but they do have a duty to fight in the war; therefor, the soldier is both under a duty to protect the members of his or her unit and he or she knows them personally; it could therefor be argued that this makes the heroism of a soldier who risks his or her life to save others in the unit something less than that of a citizen who rushes into a burning building to save a stranger; however it all depends on the situation because a soldier who faces almost certain death for his or her actions, for example by falling on a grenade, is acting in a very heroic fashion. In summary, each of these actions are heroic. The actions in the hypothetical situations can be evaluated by three criteria: first, whether the hero has any personal relationship with the person he or she is trying to save; second, whether the hero has undertaken a duty to save that person; and third, the certainty and extent of the risk that the hero undertakes.

6. What is the relationship between being a hero and being a celebrity?

Suggested Response:

A few heroes become celebrities. However, they are very few, and very few celebrities are heroes. In fact, people who seek publicity and either make money or obtain satisfaction in being a celebrity are not heroic at all. There is nothing about seeking publicity that is heroic.

7. Why was the flag raising itself not a heroic act?

Suggested Response:

The flag being raised was just a larger substitute for the first American flag that had been flown on Mount Suribachi. It was the first flag that elicited the enthusiastic response from the Navy ships and the Marines on the ground. There was no risk in raising the second flag; the effort of the Marines shown in the photograph was in raising the heavy pole. At the site of the flag raising, there were no Japanese defenders trying to kill the flag raisers. The Marines risked their lives all the time they were in combat, but they were not in combat at the moment they raised the flag. In addition, raising the second flag, in itself, killed no Japanese soldiers nor did it secure additional territory for the U.S.

(B) The Difference Between the Complexity of What Actually Happens and the Historical Interpretation of the Events;

8. At the time of the battle of Iwo Jima, the U.S. was demanding that Japan submit to unconditional surrender. In other words, the U.S. was refusing to negotiate an end to the war. The Japanese government realized that it could not win the war but wanted to get concessions in negotiations that would, for example, leave the Emperor in power and protect the military from prosecution as war criminals. A key part of the Japanese strategy to get the U.S. to the bargaining table was making it clear to America that it would be very costly in terms of American lives to invade the Japanese home islands. The Japanese made their point on Iwo Jima and later on Okinawa; the Americans realized that there would be hundreds of thousands of American casualties in an invasion of the Japanese homeland. Why didn’t this lead to the negotiations that the Japanese hoped for?

Suggested Response:

The fanatical defense of Iwo Jima followed by the similar defense of Okinawa was successful in convincing the Americans that an invasion of the Japanese home islands would be very expensive in terms of American casualties. However, this did not drive the Americans to the bargaining table to negotiate an end to the war. Instead, the expected casualties in an invasion of the home islands served as a crucial and probably decisive reason for using the atomic bomb to end the war without an invasion. Of course, no Japanese official could have anticipated this new escalation in the ferocity and destructiveness of warfare. In other words, the point made by the Japanese, that invasion of the home islands would cost many American casualties had an unintended consequence: the use of the atomic bomb on Japanese cities causing the deaths of over one hundred thousand Japanese civilians.

Finally, while there were no negotiations, the fanatical Japanese resistance did convince the Americans to make one concession: the U.S. allowed the Emperor to remain in place but without any power in return for his cooperation in ordering the several million soldiers still in the Japanese army to lay down their arms. A high percentage of these soldiers, as demonstrated on Iwo Jima and Okinawa, as well as on other battlefields, would refuse to surrender and would fight to the death despite the fact that there was no prospect that Japan would win the war. However, they would obey an order from the Emperor to give up their arms. The U.S. offered, what was in effect, a face-saving gesture to the Emperor in return for something that was very much in U.S. interests.

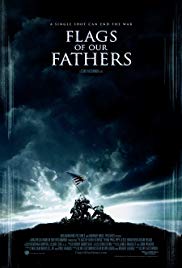

(C) The Creation of Patriotic Symbols and How They Become Important for What People Read Into Them Rather Than as Accurate Representations of Past Events

9. What is the difference between the public’s perception of the flag raising as shown in the photograph and that of the soldiers?

Suggested Response:

For the public, the photograph symbolized the heroism of the Marines on Iwo Jima and of U.S. forces during the war. For the Marines, raising the flag (i.e., the replacement flag) was an inconsequential act. There was no Japanese resistance at the top of Mount Suribachi at that time; the Marines were in no danger when they raised the flag; they were not acting heroically when they raised the flag; no territory on Iwo Jima was won by raising the flag; and no Japanese defenders were killed by raising the flag. Raising the flag wasn’t very hard, except that the metal pole to which the flag had been tied was quite heavy.

10. Why does the public of any country need heroes and symbols of national pride?

Suggested Response:

Any well-thought-out response is appropriate. Here are some possibilities. People need something to aspire to. People need something to take pride in. For any nation, these symbols are necessary to reinforce morale and a sense of national identity.

11. The movie tells us that in early 1945, the U.S. public was especially in need of heroes and symbols of national pride. What is it about the photograph that focused all that pent-up need into an explosion of patriotism?

Suggested Response:

It has a flag. It shows great effort. It appears as if the soldiers are resisting the enemy (when it was really just the weight of the metal pipe used as a flag pole). It shows soldiers working together to do something for the nation.

12. What have you learned about the symbols of patriotism?

Suggested Response:

Symbols are what people read into them rather than accurate representations of past events.