Discussion Questions Relating to Ethical Issues will facilitate the use of this film to teach ethical principles and critical viewing. Additional questions are set out below.

TRUSTWORTHINESS

(Be honest; Don’t deceive, cheat or steal; Be reliable — do what you say you’ll do; Have the courage to do the right thing; Build a good reputation; Be loyal — stand by your family, friends, and country)

See questions under Citizenship and Courage in War.

CITIZENSHIP

(Do your share to make your school and community better; Cooperate; Stay informed; vote; Be a good neighbor; Obey laws and rules; Respect authority; Protect the environment)

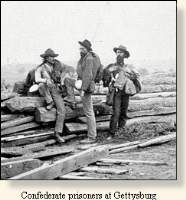

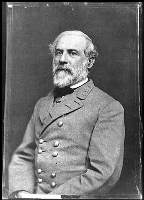

1. Patriotism is love of one’s own country. However, a civil war fractures the concept of country. People on each side believe that their opponents have betrayed a principle that is vital to the essential nature of the nation and that, as a result, they have become traitors. What principles did each side of the Civil War espouse?

Suggested Response:

On the Union side, the concept was the indivisibility of the Union and the importance to the cause of democracy of demonstrating that one of the first democratic countries the world had ever known could keep itself together. A minority also wanted to free the slaves. On the Confederate side, there was a belief in the right of individual states to leave the federal government, allegiance to their state and section of the country which they believed had been invaded, and for many a desire to defend slavery.

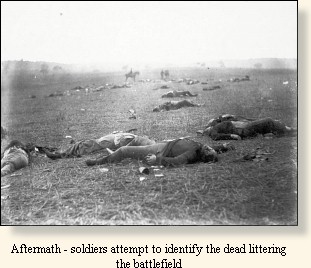

2. Why did the soldiers of the Union and Confederate armies willingly march to their deaths in the many battles of the Civil War? The history of every country is replete with men and women who have served their country at great risk and who have died as a result. These are not only soldiers but also political leaders (who are often exposed to the risk of assassination) and other controversial people such as Civil Rights workers (Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King). What did patriotism mean for them?

Suggested Response:

The word “patriot” comes down to us from the Greek word meaning “of one’s fathers.” Patriotism is a sense of loyalty to your community, a realization that who you are and what you have become depends upon that community.

Patriotism includes more than being a soldier willing to die in war. There are patriotic people who will not kill for their country. Some of these people make a greater contribution than many thousands of soldiers combined. Here is one example: James Lawson is now a retired Methodist minister. He is black. During the Korean War, he refused service in the Army as a conscientious objector and served time in jail as a result. After he got out of jail, Reverend Lawson went to India and studied Gandhian non-violence in an ashram. In 1954, while he was still at the ashram, he heard a news report about the Montgomery Alabama bus boycott (see Learning Guide to “The Long Walk Home”). Reverend Lawson then headed home and made contact with Dr. Martin Luther King, the leader of the boycott. Reverend Lawson became the most important theoretician for non-violence for the U.S. Civil Rights Movement and the conduit for the transfer of knowledge about non-violent civil disobedience from India to the U.S. Reverend Lawson saved countless lives and helped with the peaceful resolution of a serious moral contradiction in U.S. society. You can see pictures of Reverend Lawson training college students to conduct the first lunch counter sit-ins in a documentary called A Force More Powerful. Reverend Lawson was patriotic, but he was not willing to take another life or participate in a military establishment that would.

3. How can people act in a patriotic way if their country has decided to go to war but they think that it was a bad decision? This has been a question for many people in the U.S. during the last three substantial wars that the country has fought: Vietnam and both Gulf Wars.

Suggested Response:

Patriotism is a value that can be easily manipulated by unscrupulous people, including people in the media, politicians, and government officials. See All Quiet on the Western Front. The answer requires a look at the role of the majority and the role of the minority in a democracy. In the U.S., war is declared by the majority acting through the Congress, the people’s elected representatives. In many other democratic countries, war is declared by parliament, also the people’s elected representatives. Once Congress or parliament decides that the country will go to war, citizens have an obligation to support the war effort, unless they are conscientious objectors to all wars. However, that doesn’t mean that citizens lose the right to speak out against a policy of their government with which they disagree, including the decision to go to war. Actually, a citizen has more of an obligation to speak out on issues that involve life and death, than with any other issue. Protesting a war probably does undermine to some extent the morale of the troops risking their lives on the battlefield. (People who don’t understand the proper role of dissent in a democracy will claim that there should be no dissent during a time of war.) But there is a larger and more important principle at work, that is, the necessity of free speech and public debate in a democratic society. For example, most would now agree that the Vietnam War was unwinnable, that it was bad policy, and that the lives sacrificed in that war were wasted. The people who demonstrated against the Vietnam War were right and it was important that they spoke their minds. The anti-war protests were a major impetus behind the U.S. getting out of that war. (However, those opposed to the Vietnam War who vented their frustration on the troops coming home were wrong. The troops were not at fault. Any fault lay with the majority and the government.) So, for those who oppose a war, in almost every case patriotism involves supporting the war effort but denouncing the war at the same time.

Being patriotic and supporting the war effort in some extreme cases is not the principled thing to do. Some people realize that their values differ so substantially from those of their countrymen that they cannot support the war effort at all. Since war involves life and death, it makes a strong call on the loyalties, as does opposition to a war. The situation of each person is different and must be judged on its own. However, two extremes can set some parameters. Some people who cannot support a war effort but who are drafted into the military decline to serve and take the punishment provided for by law. Reverend James Lawson, a hero of the Civil Rights Movement did this. See the response to preceding question for more about Reverend Lawson. While the action is not patriotic, it is principled and satisfies any ethical or moral test. If the punishment is jail, when these people have served their time they return to society and can be as patriotic and valuable, or more so, than many soldiers. Again, Reverend Lawson and his contribution to the Civil Rights Movement is a good example. Another principled, but unpatriotic, the action is to leave the country and resign from being a citizen. During the Vietnam War, some young men went to Canada or other countries to avoid the draft. These people have sacrificed their association with the country. Whether they are readmitted to citizenship depends upon the mercy of the majority acting through its government. Several years after the Vietnam War was over, President Jimmy Carter proposed a program to forgive young men who fled to other countries to avoid the draft and to allow them to return home. This was not an endorsement of their actions, but an act of mercy.

(Additional questions on these topics are set out in the “Social-Emotional Learning/Courage in War section above.)