Changing Reasons for the North’s Involvement in the Civil War

Abraham Lincoln was not elected President based on a promise to end slavery. In fact, it was just the opposite. He promised to leave slavery alone in the South. However, Lincoln wanted to prevent slavery from extending to any free state or any of the territories. It was this position that brought on secession.

Most Union soldiers fought so that “government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.” At the beginning of the war, abolitionists were a minority. Had the war been seen as a crusade to end slavery, most Union soldiers would not have fought. In addition, the Union desperately needed the border states of Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, and Missouri. It was difficult to keep these states in the Union and would have been impossible if Lincoln had proposed ending slavery at the beginning of the war. The Emancipation Proclamation, issued on January 1, 1863, freed the slaves only in the areas of insurrection and did not affect slavery in the Border states.

Question #1: In the present day and age, is preserving the United States as one country and not letting states secede from the Union, worth fighting a bloody civil war?

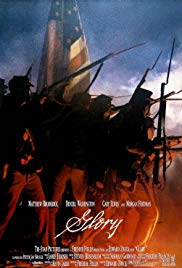

During the War several things happened to seal the doom of slavery in the United States. Among these were the fact that the death toll for the war was incredibly high and even the goal of preserving one of the few broad-based democratic governments then existing in the world, did not justify all the bloodletting. By the end of the War, 360,000 Union soldiers had died from disease or wounds suffered in battle. Many more were injured. The death toll for the Confederate armies was about 258,000. Abolitionists like Frederick Douglass had been telling President Lincoln that the war didn’t make sense if slavery was allowed to exist when the conflict was over. Second, while most Confederate soldiers were not slave owners, the power structure in the Confederacy was based on the ownership of slaves. As the war ground on, the North realized that the elimination of slavery was an efficient way to destroy the power-base of the secessionists. A third reason was the increasingly important role that black soldiers came to play in the Union Army. Authorization to enlist black soldiers was granted by Congress in July of 1862. The Massachusetts 54th, the first all black regiment began to enroll black soldiers in March of 1863. Eventually, some 179,000 black soldiers served in the Union Army (about 10% of its total strength) and another 19,000 served in the Navy (a total of 198,000 men). About 37,000 black soldiers lost their lives in the struggle; that’s about one in five of those who enlisted. As more black men took on the Union uniform, the possibility of retaining slavery after the war became more and more remote. After all, when a man had risked his life for his country, who could deny him citizenship? Who could look him in the eye and argue that members of his family or he himself must be enslaved?

Question #2: Should the U.S. allow legal or even illegal aliens who risk their lives in combat to become citizens?

Lincoln’s Second Inaugural address, delivered on March 4, 1865, is one of the most moving speeches ever given by a political leader. It was delivered when the Union Armies were ascendant and when Lee’s surrender, April 9, 1865, was just over a month away. The great bulk of Union casualties, both among white soldiers and black, had occurred by this time.

The President started the speech by reflecting on the time of his first inaugural address.

. . . On the occasion corresponding to this four years ago all thoughts were anxiously directed to an impending civil war. All dreaded it, all sought to avert it. While the inaugural address was being delivered from this place, devoted altogether to saving the Union without war, insurgent agents were in the city seeking to destroy it without war — seeking to dissolve the Union and divide effects by negotiation. Both parties deprecated war, but one of them would make war rather than let the nation survive, and the other would accept war rather than let it perish, and the war came.

One-eighth of the whole population were colored slaves, not distributed generally over the Union, but localized in the southern part of it. These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. All knew that this interest was somehow the cause of the war. To strengthen, perpetuate, and extend this interest was the object for which the insurgents would rend the Union even by war, while the Government claimed no right to do more than to restrict the territorial enlargement of it.

Neither party expected for the war the magnitude or the duration which it has already attained. Neither anticipated that the cause of the conflict might cease with or even before the conflict itself should cease. Each looked for an easier triumph, and a result less fundamental and astounding. Both read the same Bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes His aid against the other. It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces, but let us judge not, that we be not judged.

The prayers of both could not be answered. That of neither has been answered fully. The Almighty has His own purposes. “Woe unto the world because of offenses; for it must needs be that offenses come, but woe to that man by whom the offense cometh.” If we shall suppose that American slavery is one of those offenses which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued through His appointed time, He now wills to remove, and that He gives to both North and South this terrible war as the woe due to those by whom the offense came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a living God always ascribe to Him? Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said “the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.”

With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.

Abraham Lincoln was assassinated on April 14, 1865, just 40 days after his second inaugural address.

Question #3: Would you be willing to donate a kidney to allow another person to live? How is this the same or different than joining the army to fight in a war in which there were very high casualties?

[End of Handout]