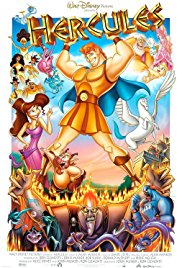

This film is a popular Disney rendition of the Greek myth of Heracles, which would be unrecognizable to an ancient Greek.

Selected Awards:

1998 Academy Awards Nominations: Best Music, Original Song for “Go The Distance.”; 1997 Annie Awards for: Best Individual Achievement: Character Animation Nik Ranieri For the character “Hades”; Best Individual Achievement: Directing in a Feature Production (Ron Clements & John Musker); Best Individual Achievement: Effects Animation; Best Individual Achievement: Producing in a Feature Production.

Featured Actors:

Tate Donovan as Hercules (voice); Josh Keaton Jas Young Hercules (voice); Roger Bart as Young Hercules (singing voice); Danny DeVito as Philoctetes (voice); James Woods as Hades; Lord of the Underworld (voice); Susan Egan as Meg (voice); Bobcat Goldthwait as Pain (voice); Matt Frewer as Panic (voice); Rip Torn as Zeus (voice); Samantha Eggar as Hera, Hercules’ Mother (voice).

Director:

Ron Clements, John Musker.

Major. See Description above.

Through changes in the plot, characters, and values promoted and by eliminating some of the horrendous events in the original myth, Disney has reshaped the story of Hercules to uphold Judeo-Christian ethics and entertain modern children. Perhaps the best thing to do if your child sees this movie is to ignore it and the film will probably go in one ear and out the other. However, if a child expresses an interest in the myth and the Greek Gods, it seems best to talk about the real myth.

In this article, the name “Heracles,” the translation of the hero’s name from the Greek into English, will refer to the mythical character. The name “Hercules,” the translation of the Roman name for the same hero, will refer to the Disney protagonist. Below is a list of some of the ways that the makers of Hercules altered the story of Heracles:

- The relationship between Heracles and his parents is changed completely. In the film, Zeus and Hera are his loving parents. In the myths, Heracles was the son of Zeus and Alcmene, the wife of a general and former king of Mycenae named Amphitryon. Zeus took the form of Amphitryon and lay with Alcmene when the general was away in battle. Hera is not happy with Zeus’ infidelity and comes to hate the child when Zeus tricks her into nursing the infant for a few weeks.

- Zeus has the same physical traits as the common picture of Jehovah- an old man with a flowing white beard, who is good and just. Hercules’ Zeus is monogamous and kind, unlike the Zeus described in Greek myths. The Greek Zeus enjoys sleeping with women, has a nasty and short temper, and does anything he wants without any qualms over the consequences.

- In the film, Zeus gives Hercules the flying horse Pegasus who becomes a faithful companion to his master. In the myth, Heracles did not have the Pegasus, who belonged to the hero Bellerophron.

- Hercules gets adopted by two loving elderly farmers, named Amphitryon and Alcmene, the name of the mother and stepfather of Heracles.

- Hercules doesn’t know about his divine origins late in adolescence. Heracles knows that Zeus is his father from a young age.

- In the film, Zeus and Hera are portrayed as a loving married couple. In the Greek myth, the couple continually fought and they were often at each other’s throats.

- In the film, Hercules is given a mentor who does not appear in the myths. His name is Philoctetes (“Phil” in the film) and he has trained many heroes. In the myth Philoctetes was a warrior who fought alongside Heracles. Phil claims to have the mast of the Argos, the ship on which Jason and the Argonauts (including Heracles) sailed to their adventures. Phil also claims to have trained Achilles, Odysseus, Perseus, Jason, and Theseus. For this to be true, the Trojan War would have already had to have ended, but in the myths, Heracles lived long before the Trojan conflict. Phil is also a satyr, probably inspired by the myth of Chiron, who was a centaur that trained heroes.

- In the film, Hercules defeats the centaur Nessus while defending Megara. In the myths, Heracles kills the centaur Nessus as it was trying to rape Heracles’ second wife, Deianira, while ferrying her across a river.

- Hercules brags to Zeus: “You should have been there, Father! I mangled the minotaur, grappled with the Gorgon . . . ” However, in the myths, it was Theseus who killed the Minotaur and Perseus who beheaded Medusa.

- Hercules’ relationship with Megara is also greatly changed. Megara is introduced as a maiden who sold her soul to Hades to save the life of her boyfriend who promptly abandoned her for someone else. In the myths, Megara is the daughter of the King of Thebes, and is given to Heracles to be his wife. Heracles kills Megara and their children in a fit of madness sent by the jealous goddess Hera. In the movie, Megara survives and lives happily ever after with Hercules.

- Hades didn’t hate Hercules or try to take over Mount Olympus.

- Hades doesn’t purchase souls (this is a Christianized element creeping into the story). Megara didn’t sell her soul to Hades. The divine being who hated Heracles was Hera, who was angry at Zeus’ infidelities and because Zeus tricked her into nursing Heracles.

- The Hades character in the film is more like the Christian Satan than the Hades of the myths. Hades was never liked by the Greeks because, being mortal and fearful of death, many considered him a hateful god. However, Hades was also viewed as neutral, being in charge of what is the Greek equivalent to Christian purgatory. In the movie, Hades is portrayed as being completely evil and has many of the physical characteristics as the Christian Satan. In the film, the underworld is portrayed as little more than Christian hell.

- The Hydra was in Lerna, not outside Thebes as is shown in the movie.

- In the film, Hades sends his two minions with a potion to kill baby Hercules. They become snakes to kidnap the child. In the myth, Heracles is abandoned by his mother Alcmene for fear of Hera’s wrath and it is Hera who sends the snakes when Hercules is returned home.

- The Hercules in the film still has superhuman power because he did not drink every drop of the potion. In the myth, Heracles has god-like powers because Hera nursed him (while she didn’t know who he was).

- Hades is usually portrayed as an ambiguous and only slightly evil god who does his job as needed and without any of the blatant characteristics as he has in the film. In Hercules, Hades is seen wearing all dark, with a darker shade of skin than the other gods, and flame for hair. Hades in the film is shown as having been forced to take the Underworld, and wanting to conquer Olympus as revenge upon Zeus and the other gods.

- In the myth, Heracles undertakes the twelve labors to atone for murdering his wife and children while in a fit of madness sent by Hera. While Heracles accepts the blame for what he did, much of the blame is assigned to Hera who had always hated Heracles. Heracles’ crime and the concept of atonement are missing from the movie. Four of the twelve labors are shown and they are transmuted into situations in which Hercules is attempting to protect people from various monsters.

- In the movie, Hades is almost able to conquer Mount Olympus. There was no such war in the myths and no conflict between Zeus and Hades.

- Audiences who watch the movie learn that Zeus forced Hades to take the underworld, when in the myth Zeus, Hades, and Poseidon drew lots to see who would rule the Underworld, the Seas, and the Skies.

- Four labors are shown in the film: killing the lion, the boar, the bird, and the Hydra. Hercules is not shown capturing the hind, clearing the stables, capturing the bull, rounding the mares, stealing the girdle, fetching the apple, capturing the cattle, or capturing Cerebus. There is also a mention of Hercules defeating the Gorgons, which is something that Perseus did in the myths.

- In the film, souls are shown as something easily taken from the Underworld back into life, while in myth, the only one who was able to almost take a soul back was Orpheus and he ended up failing.

- Hercules dies, or comes very close to dying, but he is able to survive and become a god again. Heracles was poisoned by a shirt given to him by his second wife who had been tricked by Hera into believing that it held a fidelity charm. Heracles is, however, able to become a god, when Zeus convinces Hera to “give birth” to Heracles again. In the film, Hercules also gets the chance to stay a god, but since mortals are not allowed on Mount Olympus, he decides to stay on Earth with Megara and live happily as a mortal and not happily ever after. There are shades of The Odyssey in that scene.

- In the myth, Titans were not all brutes or personality-less monsters controlling elements as they are portrayed in the film.

- The Moerae are three sisters who determine the fates of humans. They do not share an eye. It was the Graiai who shared an eye. They were sea spirits and did not determine the fate of people. Hercules never met them. It was Perseus, not Hades, who stole the eye and wouldn’t give it back until they told him what wanted to know.

- Narcissus never made it to Olympus as portrayed in the film. In the myths, he was a victim of the gods’ cruelty and ended up looking at his reflection in the River Styx.

- In the film, the River Styx looks like a river of souls and Charon doesn’t exist in the underworld of the movie. His place is taken by a skeleton.

- Mythically, there are nine muses not just the five shown in the film.

- Hercules has no siblings in the film, whereas Heracles had a half-brother, Iphicles.

- Zeus is portrayed in the film as being the sole reason why the Titans fell. In the myths, others participated in the war against the Titans.

- The climax of the movie focuses upon Hercules helping the gods overcome a revolt by Hades and the Gigantes, monsters of the Titan era. In the myths, the Titans were sent by Gaea, a Titan herself and grandmother/mother to some of the gods. She released the Gigantes as punishment for imprisoning the Titans. However the film changes it. Hades unleashes the Gigantes to take over Mount Olympus and Ancient Greece, as revenge against Zeus for forcing him into the Underworld. This is a battle that the gods will win only if Hercules can fight on their side.

- The Cyclops were not allies of Hades, but instead were allies of the Olympians in the war with the Titans.

- Hephaestus makes lightning bolts for Zeus. He is shown standing straight and tall. However, in Greek mythology, Hephaestus was a cripple.

- The Titans didn’t attack Zeus. It was Zeus who attacked his father Cronos and the Titans.

- Hercules rejects the life of a god on Olympus and lives as a mortal with Megara. In the myth, after Hera poisoned him with the cloak, he died. However, on the funeral pyre Heracles becomes immortal. He is reconciled with Hera who gives him her daughter Hebe in marriage. Hercules lives on Olympus with his new wife and a new family.

In addition to websites which may be linked in the Guide and selected film reviews listed on the Movie Review Query Engine, the following resources were consulted in the preparation of this Learning Guide:

- Graves, Robert. The Greek Myths. London: Penguin, 1992. Print.

- Hamilton, Edith. “Hercules” Mythology. London: Little, Brown, 2000. 224-243. Print.

- Morford, Mark P. O., and Robert J. Lenardon. “Chapter 19 Heracles.” Classical Mythology. New York: Oxford UP, 2007. 315-37. Print.

- Slater, Philip Elliot. “The Multiple Defenses of Heracles.” The Glory of Hera: Greek Mythology and the Greek Family. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1992. 337-96. Print.