1. See Standard Questions Suitable for Any Film.

GENERAL QUESTIONS

2. What is a “culture of impunity” and how does it relate to the “rule of law”?

Suggested Response:

A culture of impunity is one in which the aggressive or powerful are permitted to take what they want and to hurt others without being called to account. The rule of law refers to a process in which laws are created through a democratic process and then enforced according to their terms without favoritism for any particular group.

3. Could the Rwandan genocide have been stopped?

Suggested Response:

Yes. If the common people of Rwanda who had been enlisted to perpetrate the genocide had said “no” (as some did, but not enough). If the leaders of society such as the politicians, the clergy, the business people, or the army, had calmed things down, there would have been no genocide. If the international community had sent about 5,000 troops with equipment and a mandate, the killing would have stopped.

4. Who is to blame for the Rwandan genocide of 1994?

Suggested Response:

Many people. First there are the killers themselves, the people who pulled the triggers and swung the machetes. Then there are the leaders of Rwanda during the time of the genocide and for decades before, especially those who incited the populace, organized the killing, and gave the orders. Then there are the Belgians whose “divide and rule” strategy exacerbated the enmity between the Tutsis and the Hutus. They are followed by the French who equipped and trained the extremist army. Those in Rwanda and throughout the world who stood silent and did nothing while the genocide raged must also bear some of the blame. There is also the international community which failed to intervene to stop the genocide, particularly the United States (the only superpower left in the world at the time), and France and Belgium, which had historic ties to the region.

5. What is necessary for a genocide?

Suggested Response:

See What Makes a Genocide?.

6. Can genocide happen by accident?

Suggested Response:

No. It is always planned and requires a hierarchy of command to execute.

7. Should the U.S. have taken the lead in getting the international community to intervene to stop the Rwandan genocide?

Suggested Response:

Reasons supporting intervention: According to the commander of UNAMIR, who was the senior international military official on the ground at the time, five thousand well equipped and determined U.N. troops would have prevented the vast majority of the murders. Thus, a very small international force would have had a large impact. Just as Gandhi, Mandela and Martin Luther King elevated the morality of the world community by their actions, the leaders in power during the Rwandan genocide allowed the level of international morality to deteriorate. Reasons that the international community should not have intervened: Military commanders on the ground are not always the best reporters. There was little good intelligence from Rwanda. There were no strategic interests in Rwanda for the U.S. or the international community. For example, Rwanda has no important natural resources. There was an ongoing civil war and a possibility that international troops would get caught in the cross-fire. There was no legitimate government to request intervention. Given the fact that the best and most available troops would be from the developed countries and would be white, it could appear to be a colonialist venture. Note that the consensus of opinion, now some 10 years later, is that the U.S. should have intervened. The man who was President of the U.S. at the time, Bill Clinton, has stated that allowing the Rwandan genocide to continue was a major policy failure. A few years later, the U.S. led an intervention in the former Yugoslavia which stopped the genocide of Muslims (ethnic Albanians). President Clinton, in justifying this intervention, cited the failures of Rwanda and the desire of the U.S. not to make the same mistake twice.

8. What is the concept of national sovereignty and what is R2P?

Suggested Response:

National sovereignty is the exclusive right of a nation to exercise supreme authority over its people and its physical territory. When a national government embarks on a campaign of genocide or human rights violations, or when it is unwilling to protect the human rights of its people, the concept of national sovereignty has historically restricted international intervention. The Rwandan genocide of 1994, in which the government-sponsored the genocide and resisted any international intervention, showed once again the deficiencies of this concept. In Kosovo in 1999, when the Serbian dominated Yugoslav government was murdering and uprooting its Muslim ethnic Albanian population, learning from the experience of Rwanda, the international community ignored national sovereignty and stopped the genocide through armed intervention. International law often develops to describe the practice of nations. Diplomats described the concepts inherent in the Kosovo intervention and many other peace keeping operations as the “responsibility to protect”. In other words, people in grave danger have the right to expect protection, and that countries in which those people live have a “responsibility to protect” (“R2P”) them. If the national government failed to protect its citizens, the international community had the R2P. Thus, national sovereignty becomes an outmoded concept. For more, see HUMANITARIAN INTERVENTION IN

THE 21ST CENTURY — The Responsibility to Protect

9. Can a country with a repressive government, or one which has been engulfed by political and social chaos, go directly to a multi-party democracy or must they go through transitional stages which fall short of full representative democracy?

Suggested Response:

It is possible but difficult. See, for example, the struggles of Taiwan, Korea, Iraq, Argentina, Chile, Russia and the former communist countries of eastern Europe. People in Uganda who remember the terrible regimes of Idi Amin and Milton Obote are grateful for the less than democratic but stable government of Musaveni. In an April 2006 article in the L.A. Times, several Iraqis were reported as having voiced the wish that a “benevolent strongman” — anyone short of Sadam Hussein — would seize power and restore order.

10. The genocidaires have been treated well in the prison run by the International Criminal Tribunal. They receive adequate food. They are allowed to pray. If they are ill they receive medicine. This is much more than they gave their victims and, in fact, they are living better than many innocent people in Rwanda. Should they be treated this well?

Suggested Response:

It seems incongruous in this case but prisoners should be treated in a humane fashion. Once a police agency takes power over a person it has a responsibility to treat the prisoner in a humane manner. These prisoners were being treated by international standards which were much better than Rwandan standards.

11. Are the international tribunals in Arusha, which are prosecuting only a few high profile genocidaires, just a way for the international community to wash its hands and pretend that justice has been done?

Suggested Response:

Everyone has a right to justice and providing justice is an important function. The international tribunal focuses the world’s attention on the problem of genocide. However, the tribunal can only be part of a multifaceted response. Whether the tribunals are a part of the international community washing its hands of the genocide will be determined by what happens in other areas.

12. How does a society move forward from a genocide?

Suggested Response:

It has to be very hard. See Does Rwanda Have a Future?

13. European colonial powers held sway over large populations with a small number of troops through technological superiority and the strategy of “divide and rule”. The Belgians pursued this strategy in Rwanda and the English ruled through division in some of their colonies. What is “divide and rule” and how was it used in Rwanda and India?

Suggested Response:

Divide and rule means to keep control by setting one group of people against the other. For example, the British were able to rule India, a country of many millions of people, with a relatively small force by exacerbating divisions between Muslim and Hindu. The Belgians did the same on a smaller scale in Rwanda by preferring Tutsi to Hutu. This bred the resentment that later helped fuel the genocide.

QUESTIONS RELATING TO “HOTEL RWANDA”

PRE-VIEWING QUESTION – The first question below will help students focus on one of the themes of the film as they view it. Ask the question before the film and let students answer it afterward.

14. At the beginning of the film, the character of the hotel manager comes home and the children at his house are playing a game. He initially asks, “Who is the winner?” He then answers his own question, “It doesn’t matter, I have chocolates” which he then passes out to all of the children. What does this show about the hotel manager and how does it foreshadow what he does in the movie?

Suggested Response:

It shows that he is a good parent and is going to take care of the people around him. It also shows how he offers food to make people happy.

15. According to the Rwandan journalist in the movie, what are the differences between the Hutus and the Tutsis? Was his description accurate?

Suggested Response:

Reporter: “According to the Belgian colonists, the Tutsis are taller and more elegant. It was the Belgians that created the division. … They picked people … those with thinner noses, lighter skin. They used to measure the width of people’s noses. The Belgians used the Tutsis to run the country. Then, when they left, they left the power to the Hutus. And of course, the Hutus took revenge on the elite Tutsis for years of repression.” The journalist blamed the Belgians for the depth of the class/caste divisions in Rwandan society, but the Tutsis who went along with the Belgian “divide and rule” scheme to institutionalize their preeminence also bear some of the blame. But of course bearing part of the blame for problems in a society is no justification for genocide.

16. What was the role of the radio in the genocide?

Suggested Response:

“Hate radio” RTLM helped set the stage for genocide by referring repeatedly to the Tutsi as “cockroaches”, vermin, and less than human. Radio announcers exhorted the Hutu to kill and broadcast the names and whereabouts of top Hutu moderates and Tutsis.

17. What does the bearded reporter say to Paul’s belief that people around the world would act when they see the footage of the murders? What do you think he means?

Suggested Response:

He said: “I think if people see this footage, they’ll say, ‘Oh my God, that’s horrible,’ and then go on eating their dinners.” There are several reasons that might cause this reaction. Here are a few: people would regard the tragedy as remote from their own lives; people are indifferent to the tragedies of others who are not like them; people feel helpless to do anything; people are racist.

18. What tactics does the hotel manager use to keep the hotel open and the people there safe?

Suggested Response:

There are several. He does favors for powerful people. He bribes people. He offers hospitality. He charms people. In his April 2006 lecture in Los Angeles, Paul Rusesabagina said that, “In Rwanda if you offer someone a drink or food and sit next to them and look them in the eye and ask them for something, it is impossible for them to refuse you.”

19. In the movie, a genocidaire offered to let the hotel manager have a few Tutsis of his own in exchange for turning over the rest of his neighbors and friends. What did the hotel manager do?

Suggested Response:

Mr. Rusesabagina bribed the man and paid for another chance for his neighbors and friends to survive.

20. When he finds out that the European soldiers are there only to take the foreign nationals of out Rwanda, Colonel Oliver tells the hotel manager that “The West, all the superpowers, everything you believe in, Paul. They think you’re dirt. They think you’re dumb. You’re worthless.” He goes on to say, “You’re the smartest man here. You got’em eating out of your hands. You could own this hotel, except for one thing … You’re black. You’re not even a nigger, you’re African. They’re not gonna stay, Paul. They’re not gonna stop the slaughter.” What did Captain Oliver mean by saying to the hotel manager that he was not even a “nigger”?

Suggested Response:

As poorly as blacks have been treated in the U.S., the whites would not have stood around while they were slaughtered en masse. Being a black African meant that, to the West, you were not worth caring about.

21. At the beginning of the movie, the hotel manager talks to his assistant about the importance of style. What role did style have in saving the Tutsi and moderate Hutu who had sought refuge in the Hotel Mille Collines?

Suggested Response:

Style is an impression of grace and ease which is often simply shown. However, it was the appearance that the Hotel Mille Collines was an operating, stylish, four-star hotel that kept the militias at bay long enough for the rescue to be arranged.

22. What were the similarities between Paul Rusesabagina and Oscar Schindler?

Suggested Response:

They both knew many in the elite of their country’s power structure. They both undertook great risks to save over a thousand people. They used their charm to delay and deflect killers from their victims. See Learning Guide to “Schindler’s List“.

23. Did the hotel manager do the right thing by staying at the hotel and not leaving with his wife and children on the first attempt to get them out?

Suggested Response:

There is no one correct answer. A good answer will discuss the conflict felt by Mr. Rusesabagina between his duties to his family and to the refugees at the hotel. He thought his family would be safe and that the people at the hotel would be massacred if he left.

QUESTIONS RELATING TO “SOMETIMES IN APRIL”

PRE-VIEWING QUESTIONS – The following two questions will help students focus on some of the themes of the film as they view it. Ask the questions before the film and let students answer them afterward.

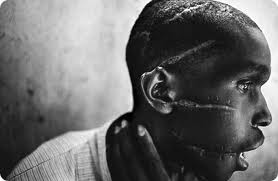

24. Look for a visual symbol of the genocide in the opening scene of Augustin’s classroom. What is it? Hint: check out the faces.

Suggested Response:

One of the boys has a scarred forehead and could have been attacked by a person wielding a machete during the genocide.

25. Look for irony in the rap song the students are listening to on a boom box after the class. What is it?

Suggested Response:

The lyrics to the song are: “I hate you. I hate you.” They are a chilling reminder of the role played by hate radio, RTLM in the genocide.

26. In “Sometimes in April”, the leader of the Rwandan government army during the genocide reminds a U.S. State Department official that Rwanda has no oil and no natural resources. Why did he say this?

Suggested Response:

He wanted to remind the official that he knew that the U.S. had no strategic interests in Rwanda and therefore no reason to risk its troops and prestige in an intervention to stop the genocide.

27. In “Sometimes in April”, the U.S. government officials say that they properly executed a policy that was in the best interests of the United States but they had doubts about the ethics of it. What did they mean?

Suggested Response:

Governments are charged with protecting the “national interest” of their countries. U.S. policy at that time was not to get involved in Rwanda. Protecting the national interest does not always involve acting ethically. For example, in the name of national interest the U.S. has often supported ruthless dictators. (Just a few examples are: the Shah in Iran, Pinochet in Chile, Noriega in Panama (until he turned on the U.S. and was removed from power by U.S. armed forces); Saddam Hussein in Iraq (until about 1991); the ruling family in Saudi Arabia; Ferdinand Marcos of the Philippines; and Chiang Kai Shek of China). That is not always the most ethical response. There was no important interest that affected the people of the U.S. or its government regarding Rwanda, such as oil or other natural resources. Thus, even though hundreds of thousands of people were being hacked to death, these officials saw no reason to risk the lives of U.S. soldiers or U.S. prestige by intervening. The U.S. had just been through a disastrous intervention in Somalia in which 18 U.S. soldiers were killed and the bodies of some of them were dragged through the streets of Mogadishu. However, this was a short-sighted view of U.S. interests. The U.S. was the undisputed leader of the international community in 1994 and had a responsibility to come to the assistance of the helpless Tutsis of Rwanda.

28. The scene in “Sometimes in April” in which the Hutu girls in the classroom at the Catholic school choose to risk death and refuse to be separated from their Tutsi classmates recalls an actual event. Virtually all of the girls were killed. Why did they do this?

Suggested Response:

The Hutu girls decided it was better to risk death than to betray their Tutsi classmates. They also decided to take a stand against the genocide by not cooperating. It is also undoubtedly true that peer pressure was involved. Some of the girls who were leaders in the class first stated that they would not go and that they would not allow their Tutsi friends to sacrifice themselves for the Hutus. The other Hutu girls could not separate from their Tutsi friends without seeming to be traitors. Clearly, both factors were operating and the girls were heroes. Peer pressure will not account for a decision by all of the Hutu girls to stay with their friends in the face of near certain death. Heroic deeds are seldom totally altruistic. There will usually be other reasons that help the hero or heroine make a courageous choice. This does not detract from the heroism.

29. The Hutu girls in the class in the Catholic girls school knew that there was a strong possibility that they would be shot if they stood with their Tutsi friends. If you had been in the class, what would you have done?

Suggested Response:

There is no one right answer to this question. One good answer is that they could have rushed the soldiers and tried to get their guns. Even if unsuccessful, they would have died trying to do something. (Note that it’s easy to reason this way after the fact.)

30. What role, if any, did the Arusha Peace Accords play in the genocide?

Suggested Response:

The Peace Accords are not to blame for the genocide. It was the reaction of Hutu extremists, fearful of losing power and privilege, that caused the problem. In addition, diplomats focused on the Accords, trying to keep them alive even while genocide was occurring. This made them reluctant to further alienate the Rwandan government out of fear that the government would withdraw completely form the Arusha Accords.

31. All genocides are gruesome. What was the special and particular horror of the Rwandan genocide compared to the Nazi extermination of six million Jews and six million Gypsies, Russian prisoners of war, Poles, the handicapped, and their political opponents?

Suggested Response:

The Rwandan genocide was person to person. The percentage of the population who participated in the genocide in Rwanda was much higher than in Germany. Although the deaths of the 12 million victims of the Nazis (Jews and non-Jews alike) were horrendous and cruel, the public was insulated from it. Most often, people were taken away from the general population and put into ghettos or moved by cattle cars to concentration camps where they were shot or gassed by government functionaries. In Rwanda, the killing was person to person, with machetes and guns, often by the friends and neighbors of the victims.

32. Honore said, “When I finally realized that I was an actor in this tragedy I chose not to live with that. I thought death would bring me peace. I was wrong. Only the truth can ease my guilt.” What did he mean?

Suggested Response:

Only by telling the truth, taking responsibility, accepting the punishment, and attempting to make amends can a person begin the process of accepting his own guilt. Honore did not want to die burdened with his guilt.

33. Remember the priest who cooperated with the Hutu officials and helped them cull the people seeking refuge in his church? He justified his conduct by saying “I do not have the power to change this situation.” Did he act correctly?

Suggested Response:

There is no one right response. He was a collaborator but then again he may have been able to save some people.

34. At the beginning of “Sometimes in April”, and again at the end of the movie, we see a meeting in which people who participated in the genocide are being called to account for their actions. What is this process?

Suggested Response:

It is called “gacaca” (pronounced ga-cha-ca) or “justice on the grass”. The word “gacaca” is derived from the Kinyarwanda word for lawn or grass. The Rwandan government tried to use gacaca to dispose of the cases of low level genocidaires. It didn’t really work because gacaca was designed for small scale property disputes and not for crimes like murder and genocide.

35. Even though the Rwandan genocide was low tech, there was, for Rwandan society, a new technology which helped spread the genocide. What was it?

Suggested Response:

Cheap transistor radios had just become widespread. This allowed the extremists to communicate with the Hutu masses and incite them to kill their neighbors.

36. Why does Augustin have difficulty taking off his wedding ring?

Suggested Response:

It would be an acknowledgment that his wife was permanently gone and that his relationship with her was severed.

37. After the RPF won the civil war, two million Hutus (including many genocidaires) streamed into refugee camps. The West, including the U.S., sprang into action and mobilized a massive relief effort. Was this the right thing to do?

Suggested Response:

Yes, better late than never. There were many innocent people among the two million, including children and others who didn’t participate in the genocide. It would be an act of genocide itself to allow them to die just because many of them had participated in the killing of the Tutsis. Just because the West didn’t act ethically when the Tutsi needed protection was no reason to justify continuing to act unethically as new situations presented themselves.

38. What was the role of the civil war in setting the conditions in which the genocide could occur?

Suggested Response:

It was a major factor. First, it led the Hutu leaders to fear for their positions of power. They used the genocide to secure their positions and deflect the people from their failures as leaders. Second, it gave the Hutu leaders a reason to give to the people to kill the Tutsi; they claimed they were traitors. Third, it caused confusion and blunted the foreign response. It is very risky to get mixed up in a civil war.

39. Give some of the code words broadcast over the radio at the start of the genocide.

Suggested Response:

“Cut the tall trees”, “clear the brush”, and “do your work”.