THE LIMITS OF MATERIALISM AND UNREGULATED CAPITALISM: The 19th and 20th centuries saw the elimination of the vestiges of feudalism throughout most of what is now the developed world. Three major economic theories arose. In capitalism, a desire for profit motivated people. Land, buildings, other property, the means of producing goods, and the means of distributing them, were owned by individuals or companies. Socialism was a reaction to the extreme hardships caused by unregulated capitalism and sought to ensure that the economy was operated for the benefit of society. In socialist economies, the state owned the major means of production and distribution. Finally, there was communism in which, theoretically, each person was to contribute according to his or her abilities and each person was to receive according to his or her needs. Communism was never actually implemented but the “communist” countries claimed to be working toward that system while pursuing a centrally planned, government-controlled economy in which the land, the buildings, the factories, the mines — pretty much everything except personal possessions — were owned by the state. Neither socialism nor capitalism was adopted in a pure form in any major economy, but different countries primarily employed one system or the other.

The experiences of the period after 1850, especially the rise of large enterprises that sought to create monopolies and the Great Depression of the 1930s, demonstrated that capitalism needed to be regulated and, in a limited way, guided by the government to prevent chaos and economic collapse. In the late 20th century, the experience of the “communist” countries (for example, the Soviet Union and China) showed that government-owned command economies could not keep pace with the modified capitalism of the Western democracies. The last half of the 20th century also demonstrated that economies with large socialist components (many enterprises owned by the government and operated for the good of all) were not as efficient at liberating the energies of the people to produce goods and services as were the modified capitalist countries. The lesson has been that in general, people work harder and smarter when they work for their own benefit, but that economies as a whole work better with certain limited government interventions.

Modified capitalist economies limit and regulate the profit motive by: (1) imposing standards and regulations (for example, a minimum wage, regulations protecting the health of workers, protections for workers’ pensions, antitrust regulations, honest trading rules for stock markets, truth in labeling, zoning laws etc.); (2) providing public services through the government (for example, public schools, medical care [in the U.S. this only extends to the aged and the indigent], city street services, garbage collection), and (3) enacting safety nets such as social security and income transfer mechanisms (welfare and progressive taxes). Through various economic mechanisms, such as central banks (called the Federal Reserve in the U.S.), insurance for bank deposits, and tax systems, these economies moderate the effects of the business cycle and influence business activity. Each country chooses its own mechanisms by which the basic capitalist structure is organized, regulated and guided.

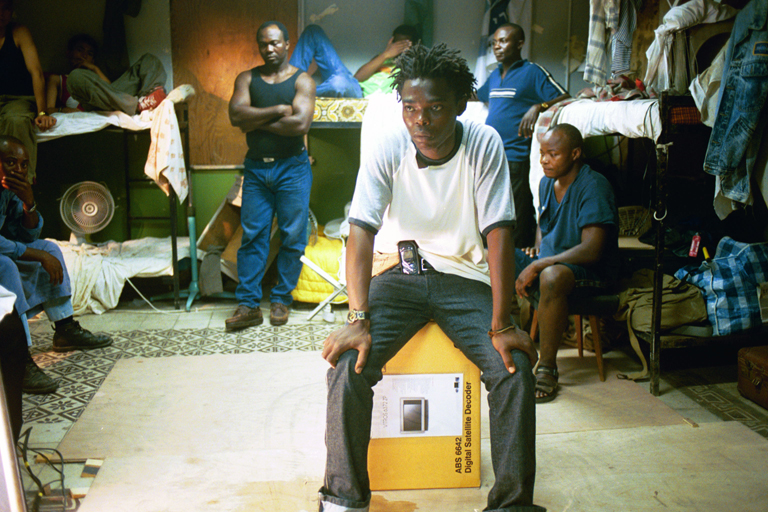

Each country also has its unique set of non-governmental institutions which ameliorate the harsh effects of capitalism such as unions, community organizations, charitable organizations, including the charitable activities of churches, synagogues, and mosques. These organizations can be used to help protect vulnerable workers (such as illegal immigrants) from the Shimis of the real world when the government fails to do so. The preceding paragraphs are very general and certainly, there are exceptions. However, this is a fair globalized view. A major theme of the film is that unregulated capitalism and rampant materialism corrupt everything they touch. Shimi lies, cheats and reduces his workers to semi-slavery. He forces his father to leave the home that the old man was comfortable in, just to make money. Salah, the father, cheats his friends by feigning injury and then using James’ blessedness, the ability to throw double sixes, to cheat his friends. James is diverted from his pilgrimage to Jerusalem, his religious beliefs, and good relations with his fellow workers. The film shows what happens when a culture thinks only of profit and has no sense of community.

IS THIS REALLY WHAT LIFE IS LIKE IN ISRAEL? — IN WESTERN SOCIETY AS A WHOLE? The film appears to be a realistic portrayal of the underside of developed Western economies that depend on immigrant labor. The system in each country may differ, but one way or another, many immigrants are exploited. Of course, there are many other situations in which immigrants are helped to make a life in their new home. James, however, is not an immigrant. He is on a pilgrimage and never intended to stay.

As for Israel, we know the following. It was a country which was founded with a communitarian spirit and a socialist ethos. That has certainly eroded of late. We assume that the movie doesn’t show a representative sample of the Israeli people. In fact, the film was well received in it its country of origin, Israel (nominated for Best Film by the equivalent of the Israeli Academy Awards). This demonstrates that there are many in Israel who see problems with the materialistic way of life.

The writer/director Alexandrowicz told TWM:

[The film is] about this concept of “frayer” [Yiddish slang for a person who allows others to take advantage of him or her; a chump, a patsy]. The character Salah in the film is teaching James not to be a “frayer.” He’s teaching him to be strong, to not let go of anything, just as he did his son. But afterwards his two sons, his own creations, turn against him, and he finds himself in a weak position in relation to them — his real son and his adopted son [James]. At one point James tells him, “Look, you can get $1 million for your plot of land. Why don’t you take it? Don’t be a frayer, take it.” The father responds, “It’s the other way around now. If I take the money I’m frayer. What do I gain from it?” This is perhaps something the Israeli consciousness should understand, that we are trapped now, into not being “frayer” in the situation. Perhaps our way out is through being exactly the opposite of what we believe, the opposite of being strong.

Interviewer: This is what you are contributing to the discourse.

Alexandrowicz: Yes. And the change of James in the film from someone who’s completely ready to be a “frayer” to someone who won’t be a “frayer” any more, and then begins to make enemies and to hurt other people, comes to a point in the end of the film where James wakes up, where he finds who he was and what he is now. And this is something that I hope for us very much. Interview of the Director by Liza Bear for Indiewire.

PARABLE: This film is a parable, “a short fictitious narrative that illustrates a moral attitude, a doctrine, a standard of conduct, or a religious principle.” A parable is distinguished from a fable in that fables usually take the form of stories about animals that are illustrative only and could not have happened in reality. A parable on the other hand deals with people and has an inherent plausibility which allows more complex issues to be explored. Article on parable. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved January 24, 2005, from Encyclopaedia Britannica Premium Service. Parables are often used in religious teachings. An example from the New Testament is the story of the sowers (Matthew 13:1-23; Mark 4:1-20 & Luke 8:4-15) in which Jesus explained that the sowers were those seeking to spread the word of God, the seed stood for the holy message, and different types of people were the locations in which seed landed, in some the seed would grow, in others it would wither, and in some it would be stolen by evil.

SYMBOLISM: There are several symbols in the film, some recognized by the characters and others not.

James’ clothing changes. He arrives in Israel in beautiful robes of golden material from his native land. His first attendance at church is in another African robe, this one white. However, as he gets derailed, he adopts Western style clothing, first for work, but then even for church. As James gets wealthier, his clothing improves, until he goes to the party near the end of the film in a fashionable white suit. When he is deported, James is wearing the traditional clothing that he had on when he arrived. However, by that time he has re-discovered his quest.

Jerusalem stands for the holy place. Of course, the true holy place is found within ourselves, in our own faith and belief, whatever that faith and belief is and wherever we may be physically located.

The trip to Jerusalem is a symbol for James’ path in finding himself and resisting the temptations of material culture.

James’ ability to roll dice and get consistent double sixes is a symbol of his blessedness. As long as James has not abandoned his quest, he is blessed. However, by the time of the party, he is no longer seeking Jerusalem (that is, he has accepted the out of control capitalist/materialist culture and has abandoned the quest for true fulfilment). Being no longer blessed, his luck at dice is gone. This symbol also affects the other characters because Salah, the father, perverts this gift (James’ blessedness) to win money at backgammon, alienating his friends.

Salah’s action in kissing the money he wins at the rigged backgammon game is a symbol of how money is substituted for friendship and affection in the unrestrained capitalist/materialist culture.

Salah’s rundown, slum-like home (with a garden that James made bloom again) is a symbol for the old pioneering spirit of Zionist Israel and a close relationship to the land, nature and community. The fact that it is surrounded by large apartment buildings shows the threat from the new unrestrained capitalist/materialist culture. The loss of this little plot of land to yet another large apartment complex is a symbol for the loss of fundamental values and relationships on which a satisfying and meaningful life depends.

IRONY: The following are some of the instances in which irony is used in this film:

When he is in the holding tank, James prays for God’s help in reaching Jerusalem. Just then, in walks Shimi, and the doors of the jail spring open. At first this appears to be an irony because Shimi is not, apparently, an answer to James’ prayers. Rather, he is the embodiment of temptation leading James away from his pilgrimage. As the story ends, in a type of double-irony, it becomes clear that Shimi is indeed the answer to James’ prayer, but not because he will facilitate James’ journey to the city of Jerusalem. Shimi facilitates James’ exposure to rampant capitalist materialism which James must experience and reject on his real quest, the effort to find his true self.

In the physical sense, James makes it to Jerusalem only as a prisoner and not as a pilgrim. This is an ironic end to his physical journey.

The minister of the congregation at which James worships is also infected by materialism. It blinds him to his true vocation, which in this case is to minister to his flock, James among them. He betrays James’ trust by using James to further the material needs of the congregation (costumes for the choir and jobs for parishioners) in a way that hinders James on his pilgrimage. The minister, rather than Salah, should have been the one to remind James that he had lost his way to Jerusalem. (The character of the minister should not be seen as a warning only to Christians, but to adherents of any religion.)

There is, of course, the irony inherent in the view of Jerusalem as a city of the Bible and the modern day city of Jerusalem. This is an irony that affects all Christians, Jews, and Muslims, who consider Jerusalem to be a holy place. The writer/director of the film said:

The first thing I thought of about the film was the fundamental, strong contradiction between the Holy Land as an abstract, spiritual entity in the mind of many people in the world, and it being Israel, a country with a very prosaic existence-a fast developing country, with a modern economy, traffic jams, shopping malls, immigration laws, and exploited migrant workers. See Director’s Statement.

Of course, the Jerusalem of biblical times probably had its underside as well.

THE MYTH OF THE HERO AND JAMES’ JOURNEY: One of the standard storylines in myth and literature is the journey of the hero. The primary components of the myth are separation, travel to another world, learning to survive in that world, the intervention of facilitators, and return. This is James’ story. He can take back to his village his understanding of the weaknesses of materialism and unrestrained capitalism, along with his renewed faith in the moral teachings of his religion. He takes as well the understanding that the physical Jerusalem is a very different place than the holy city described in the Bible, but that the important Jerusalem is a spiritual place in which each person can feel close to their sense of the meaning of the universe. James’ journey has many of the aspects of a hero’s journey. Money and material goods are the siren song of temptation. There is a person who leads him astray, actually several: Skombozi, Shimi, the minister, and Salah. James is able to pass through this world, which to him is alien, and return to his village with the prize, in this case, new wisdom.

PLOT STRUCTURE: The overall structure of the plot in this story is: (1) James goes on the pilgrimage; (2) he is diverted by the customs agent and Shimi; (3) aided primarily by Shimi, Skombozi and Salah, he adopts the materialist lifestyle and abandons the pilgrimage; and (4) James regains the right path when Salah tells James that he has lost his way and will never make it to Jerusalem, Skombozi crashes the party creating a scene, James has his epiphany, and Shimi has James arrested. Once arrested, James makes it to Jerusalem but as a prisoner rather than a pilgrim.

RELIGIOUS PILGRIMAGES: The religious pilgrimage is one of the archetypical journeys of mankind. It is found in all major religions: Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Buddhism, Hinduism, Shintoism, etc. Pilgrimages are undertaken for several reasons: to gain supernatural help; to express thanks to a deity or saint; as an act of penance; to fulfill a vow, or simply for the sake of devotion. Sometimes the pilgrimage is simply an added reason to travel to a place. The purpose of the journey of a pilgrim is to become closer to the holy and to purify the self. Pilgrims believe that when they get close to or observe sacred locations they can communicate more fully with their god. Pilgrimages are made to Jerusalem, to Mecca, to certain temples, locations of relics, graves of saints, sites of miracles etc. Christian pilgrims have been journeying to Jerusalem since 200 C.E. James’ journey began as an effort to become closer to the holiness of the City of Jerusalem. Articles on “pilgrimage”, “Buddhism;” “Judaism” and “Christianity” in Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved January 24, 2005, from Encyclopaedia Britannica Premium Service. For more, see Wikipedia Article on Pilgrimage.

There are also certain common mishaps and errors to which many pilgrims are prone. The writer/director, Ra’anan Alexandrowicz, has related to TeachWithMovies.org the following story. It was told to him by a Tibetan Buddhist Monk after a screening of the film: “It’s a famous phenomenon that Buddhists who make the pilgrimage to Lassa [the capital of Tibet and the location of an important Buddhist shrine], get completely preoccupied with the business that was supposed to fund the trip. They have a saying ‘Even if you reached the city, you might have not entered the temple.'”

There are also secular pilgrimages. For many U.S. citizens, trips to Philadelphia to see where the Declaration of Independence was signed and the Constitution was drafted, or to Washington, D.C., or to the site of the Battle of Gettysburg, are meaningful journeys which give rise to strong emotions and cause them to reflect on their heritage.

Writer/director Ra’anan Alexandrowicz put it this way:

I think there is a bit of James in each and every one of us. We learn too well, as people and as societies, how to talk about our noble dreams as an easy way of forgetting them. I think each of us has his or her Jerusalem toward which we aspired to reach. Whether we reach it, or even remember where we were headed, is another issue. Director’s Statement.

MATERIALISM AND ORGANIZED RELIGION: The writer/director, Mr. Alexandrowicz, told TeachWithMovies.org that the Pastor character is not intended to be particularly Christian, but could be from any religion: Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, etc. He stated that “It is my observation that even spiritual institutions are open (very open) to corruption by the influence of materialism to use their believers in the wrong way. This is based on things I’ve seen and heard in quite a few places around the world. So I think it is a healthy lesson for students to clearly observe the abuses of materialism in any system, even if it has a spiritual affiliation.”