In Roman times and the Middle Ages, Ireland was inhabited by Celtic tribes. In the 5th century, Saint Patrick sought to convert the entire island to Christianity. Although Patrick was not successful in his lifetime, by the 6th century Christianity had triumphed. The Anglo-Normans first invaded Ireland in the 12th century. Over several hundred years the entire island was subdued. It was thereafter ruled from England in a manner that was often callous and inhumane. The Irish rebelled frequently. The laws imposed by the British discriminated against Catholics, a group which comprised the vast majority of the inhabitants of the island. The laws favored Protestants which included the English landlords, police and others sent from England to help subdue the island. Still, the periodic rebellions continued. In an effort to secure peace in Ireland, Parliament passed the Act of Union in 1800, incorporating Ireland into Great Britain and removing the laws favoring Protestants. The leaders of Parliament sought to combine Union with Catholic emancipation. But largely due to the opposition of the King, Catholic emancipation did not materialize for another 30 years. The periodic revolts and struggles for independence and home rule continued.

Before the Potato Famine (1845 – 1849) the population of Ireland was estimated to be about eight million people. Most of them relied on the potato for nutrition, which had been brought over from South America. The Potato Famine, was the result of a fungus which caused the potato plants to turn black and rot in the fields. It reduced the population (through starvation and emigration) by about 2.5 million. All during the Potato Famine the wealthy, and mostly English landlords, continued to export grain to England. The English government did not take effective steps to ameliorate the famine. Instead, many of its policies made the situation worse, such as the export of grain from Ireland to England. Emigration by Irish people seeking better economic opportunities continued after the famine, to the present day. The present population of Ireland is estimated to be 3.5 million people, less than half the 1840 figure.

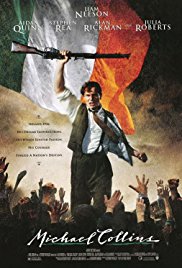

The Easter Rebellion of 1916 was a turning point in Anglo/Irish relations. Before that time, the Irish (including most groups that advocated independence) had largely supported England in the First World War. A splinter faction of the independence groups (including Collins and De Valera) attempted an armed revolt seizing the Dublin Post Office and various other locations. But the rebellion was never supported by the Irish people and the rebels knew when they began that they had no chance of winning. The British imprisoned the participants and executed 15 leaders. This overreaction aroused public indignation. In 1917, the British further inflamed public opinion by threatening to impose conscription to fill the ranks of the British army during the First World War. Sinn Fein, which had been a little known group supporting a separate Irish parliament but retaining the English monarch as the king (or queen) of Ireland, changed its position to support full independence. It swept the 1918 parliamentary elections and Eamon De Valera was chosen to lead a shadow government. Sinn Fein waged war against the British occupation from 1919 – 1921. Its violence was directed almost exclusively to the British occupying forces. Michael Collins was the Finance Minister and led the armed resistance, developing a network of informants and waging the first modern urban guerilla war. Collins’ guerilla warfare tactics were studied and adopted by such disparate leaders as Mao Zedong (China) and Yitzhak Shamir (Israel).

In 1921, Collins was selected to lead a delegation to peace talks with the British. The delegation obtained an agreement for home rule but Britain would not concede full independence. This compromise was unacceptable to many in the Sinn Fein, including De Valera. A plebiscite was held and the Irish people voted overwhelmingly in favor of home rule and the Irish Free State. The dissidents began a civil war and Collins was appointed commander in chief of the Irish Free State forces. He was assassinated on August 22, 1922, by members of Sinn Fein who were opposed to the peace treaty. The war went on for two years and ultimately the Irish Free State prevailed. It continued in existence, despite resistance from Sinn Fein until full independence was attained in 1949 with the establishment of the Republic of Ireland.

After watching this film, the children in our family became very passionate in their admiration for Collins. The parents took the position that the Irish would probably have won their independence through civil disobedience. Since all the killing might have been avoided, they argued, Michael Collins bore responsibility for many murders and was not as admirable as, for example, Mahatma Gandhi. The parents argued that considering the prejudices against people with brown skin that prevailed in the first half of the 20th century if South Africa and the British Empire eventually capitulated to Gandhi’s civil disobedience campaign, the British would have been even more responsive to civil disobedience by the Irish. After all, the Irish are white Europeans who practiced a Christian religion (Catholicism) whereas the Indians were a dark-skinned people from a different religious and cultural heritage. (See Learning Guide to “Gandhi”.) The children attempted to rebut this argument by asserting that the British, at the time, considered the Irish to be less worthy of consideration than the Indians, who had a complex and ancient civilization. The children also argued that people can be judged only in relation to their society and their times. They questioned whether civil disobedience played a major role in the granting of Indian independence. The parents countered by stating that not only did civil disobedience play a central role in forcing the British to relinquish control of India but that it made the process more peaceful. The parents reminded their children that taking a life, even the life of an oppressor, is such a terrible thing that people should be called to account for killing if there is any way to avoid it. These points, and many more, provoked very spirited (and educationally beneficial) debates.

Civil disobedience and its power were not unknown to the Irish in the early 20th century. Before Michael Collins’ campaign of violence against the British occupying forces, Irish prisoners brought the British to their knees and obtained release from prison through hunger strikes.

Should Michael Collins and the IRA of the 1920s be condemned as terrorists? The historical record shows that it was the British occupiers who used indiscriminate violence. The incident at the soccer game portrayed in the film is a reasonably accurate portrayal of an historical event. At other times, the British made the decision that their troops should not worry about innocents who may be killed in a cross fire. The British destroyed homes to punish communities for harboring IRA men. The Irish, on the other hand, focused their death squads and flying columns on the British intelligence forces and the occupying troops. Some in the IRA proposed a plan to take a machine gun to England and shoot up a line waiting for a movie, but this was rejected, with Michael Collins being one of the primary opponents of the plan. The Irish resisters did burn warehouses in England. However, the Irish resistance led by Michael Collins was very different from the terrorists of today who attempt to gain their ends by the murder of innocent civilians.

More Historical Inaccuracies: The film does not fully describe Collins’ true triumph over the British. Historically, the British had used informers and a powerful secret police to maintain power in Ireland. Most of the Irish independence movements were infiltrated with British agents. Michael Collins turned this around on the British and infiltrated the “Castle” (the seat of the British military government) at all levels, not just through one person, as is shown in the film. It was said that when a British Officer drafted an order, Collins had a copy before it was received by the subordinate for whom the order was intended.

The portrait of De Valera is inaccurate. Many historians disagree with the idea that De Valera manipulated Collins into attending the peace conference. There is no evidence that De Valera was complicit in Collins’ murder. It was reported that he wept for the entire day after it occurred.

Michael Collins and Harry Boland competed for the hand of Kitty Tiernan.

Eamon De Valera was an American of Irish descent who returned to Ireland for college and stayed. De Valera reversed his opposition to the Irish Free State in 1927 and in 1932 was elected its President. He also served as prime minister of the Republic of Ireland for two terms. He was elected President of the Republic of Ireland from 1959 to 1973. De Valera is said to have remarked that “History will record the greatness of Michael Collins, and it will be recorded at my expense.” This film is part of that process. The portrait of De Valera in the film is apparently incorrect and unreasonably negative. It is a dramatic device to heighten the image of Collins as a hero.