1. El Pueblo Nuestra Señora Reina de Los Angeles: according to some historians this was an early name for Los Angeles.”

1. El Pueblo Nuestra Señora Reina de Los Angeles: according to some historians this was an early name for Los Angeles.”

2. Jalisco and Colima: States in Mexico.

3. Andale, can cuidado: Come on with care.

4. Hazle un lugar ahi: Make a place for him there.

5. Niños: children.

6. Tu café con leche está listo:Your coffe with milk is ready.

7. Mi cafecito: My coffee.

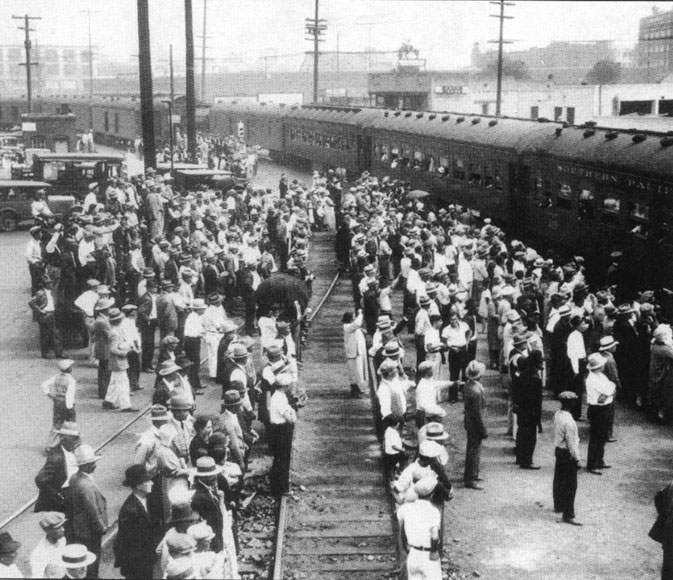

8. La Migra: The Immigration and Naturalization Service (now called the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Service, “USCIS”).

9. Por favor, Señor: Please, mister.

10. Pinche: ***.

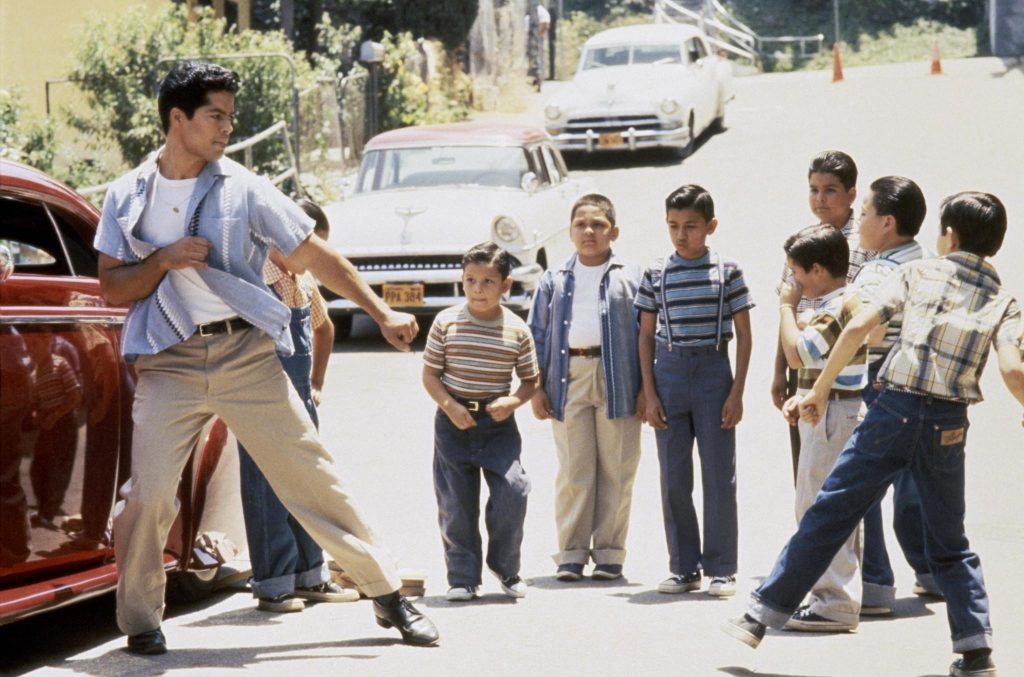

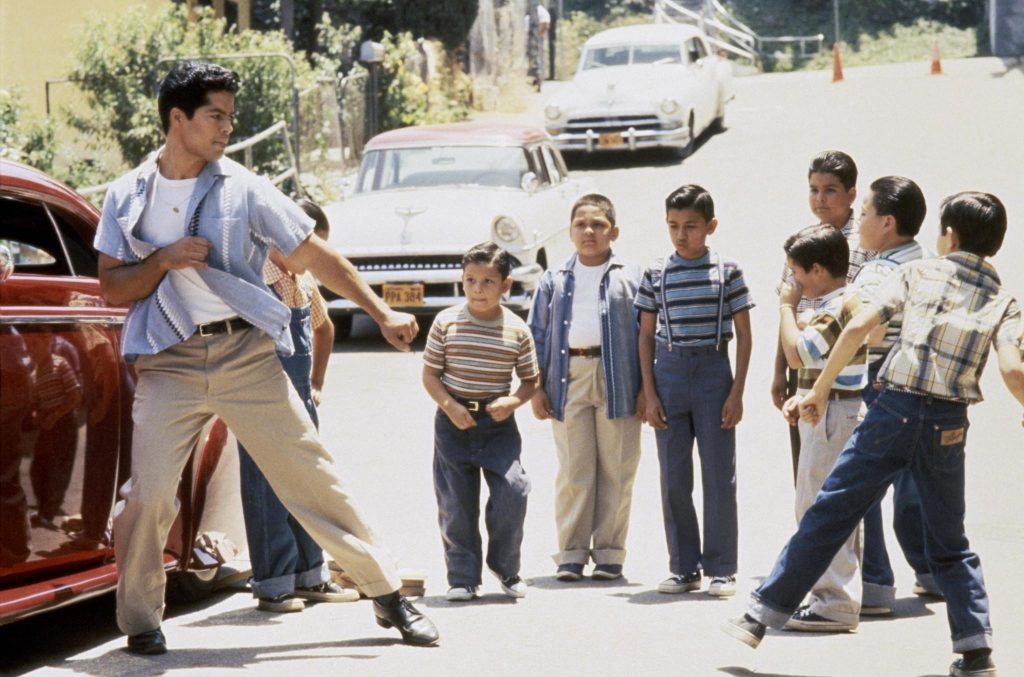

11. Pachuco: a male member of a Mexican-American subculture in the 1930s to 1950; pachucos wore zoot suits, had an exuberant nightlife, and engaged in flamboyant public behavior; some were associated with street gangs.

12. hermano, hermana: brother, sister.

13. aboratte*: colloquial for “go away,” “leave,” “disappear yourself.”

14. Cholo: a person who is of mixed Spanish and native American heritage; a half-breed; it is often pejorative.

15. Ese: slang to refering to the person you are talking to; it is often seen as a perjorative reference to a person of Hispanic heritage.

16. Pues nada: well, nothing.

17. Apurate: hurry up (When Irene says this to her sister Toni, she is being sarcastic.)

18. Machismo: male chauvinism.

19. Brindis: a toast;

20. Felicidades: congratulations;

21. Ella es la mama: She is the mother.

22. No te hagas rogar: You don’t have to beg.

23. Salud: To your health.

24. Salud a todos: To everyone’s health.

25. Mariachi: a form of folk music from Mexico.

26. Los apostoles: The Apostles.

27. Puta, puto: prostitute; when referring to a man it is a general insult.

28. Que Pasa: What’s going on?

29. Vato: Dude.

30. Carnal, carnala: buddy, relative.

31. Que te metas para adentro: What did I say about staying inside?

32. Milpa: cornfield.

33. Chavalito: little boy.

34. Jefe: boss, leader, chief, commander; in a family, Father; Jefecita is Mother.

35. Mota: slang for marijuana.

36. No es tiempo para esto: This is not the time for this.

37. Sinverguenzas delincuentes:criminals

38. Pero tu . . . . : But you . . . .

39. No tienes consciensia: You have no conscience.

40. No tienes dignidad: You have no dignity.

41. A la chingada con eso!: F..k that!

42. No hagas esto, mijo: Don’t do this, son.

43. No hagas esto: Don’t do this.

44. Largate: Get out of here.

45. Que estas haciendo: What are you doing?

46. Mijo: Son.

47. Chinga tu madre.: F__k you.

48. Y mi jefita, como está?: How is mother doing?

49. Y mi jefe, qué dice?: And Dad, what does he say?

50. Nada: nothing.

51. Vete: Get out of here.

52. Hasta Mañana: Until tomorrow.

53. Apurate: Hurry up.

54. Mira: Look at.

55. Con permisso: Excuse me.

56. Vas a ver:You’ll see.

57. Quadese ahi: Stay there.

58. Está muerto: He is dead.

59. La pinta*: slang for prison.

60. Hola: Hello or Hey there.

61. Callate: Be quiet, Shut up.

62. Hijo de: Son of . . . .

63. Un Sacerdote: a priest.

64. mi vida: my life, my darling

65. Mucho gusto: nice to meet you.

65. Mucho gusto: nice to meet you.

66. Mi querido: my darling

67. Y (as in “Y Paco”: and.

68. Abogado: lawyer.

69. Hombre: lman.

70. Mujer: woman.

71. Hombre y mujer, ¿sabes?: Man and woman, understand?

72. Pero: but.

73. Este pastel esta muy bueno: This cake is very good.

74. Baboso: lovestruck, drooling, fawning.

75. Ruca: Old maid.

76. Pendejo: jerk, coward.

77. Cabrona: bitch.

78. Es la pura verdad: It is the pure truth.

79. Vos tenes que ayudarme: You have to help me.

80. Me acabo de casar y no se adonde voy a ir: I just got married and I don’t know what I’m going to do.

81. ¿Vos sabes dodne está Jimmy?: Do you know where Jimmy is?

82. No puede creer esto: I can’t believe this.

83. Ya lo llame: I’m going to call him now.

84. ¿Que Voy a hacer?: What am I going to do?

85. Oye: Hey.

86. Ven acá, hijo: Come here, son.

87. Explícame qué pasa aqui: Explain to me what’s going on here.

88. Chingao: f__cked up.

89. Ay, Dios: Oh, God.

90.Porqueria politica: political crap.

91. Sagradas: sacred.

92. Y tu te callas: And you shut up.

93. Te fregaste: You messed up.

94. No quiero: I don’t want.

95. Vato loco: Crazy dude.

96. Canton: lang for a house in the barrio.

97. Viva la Raza: Long live the mestizo race.

98. Entonces qué: Then what.

99. ¿Eres mi hombre?: Are you my man?

100. ¿Si o no?: Yes or no?

101. Te regalo una rosa: I give you a rose.

102. Si, vamos: Yes, let’s go.

103. No se si esta desnuda: I dont know if it’s naked.

104. O tiene un solo vestido: or just one dress — this line and line # * are from the album “Bachata Rosa” by Juan Luis Guerra.

105. ¿Que dolor, no?: It was painful, wasn’t it?

106. Grandissima ciudad: Big city.

107. Los soldados: the soldiers.

108. Ay, imuchacho travieso, sinverguenza: mischevious scoundrel — can’t find a meaning for “imuchacho.”

109. Ven aqui: come here.

110. Te voy a pegar Mocoso: You brat. I’m going to spank you.

111. Mocoso, ya veras: Sntty nosed squirt, you will see.

112. Muchacho malcriado, ahora veras: spoiled boy, now you will see.

113. ¿Que pasa aqui, senora?: What’s going on here, Senora?

114. Pero ese nino es un desgraca: But, that child is a disgrace.

115. Abuelita, Abuelito: grandmother, grandfather.

116. te voy a comer vivo, vas a ver: I’m going to eat you alive, you’ll see.

117. Mucha hierba: a lot of grass.

118. Es que no puede, jefe: This can’t be done, Dad.

119. ¿Si, mi Chapulin?: What is it my grasshopper?

120. Hola, mi amor. ¿Ququé haces?: Hello, my love, what are you making? or Hello, my love, what are you doing?

121. Calma: calm down.

122. Escucha a Mami: Listen to mother.

123. Lo siento, mijo: I’m sorry, son.

124. Salud: Cheers.

125. Qué pasa: What’s up?

126. Tu café con leche está listo:Your coffe with milk is ready.

127. Vamos hombre. Andale: Go man, hurry.

128. Andae: Come on.

129. Mi familia: My family.

1. El Pueblo Nuestra Señora Reina de Los Angeles: according to some historians this was an early name for Los Angeles.”

1. El Pueblo Nuestra Señora Reina de Los Angeles: according to some historians this was an early name for Los Angeles.” 65. Mucho gusto: nice to meet you.

65. Mucho gusto: nice to meet you.