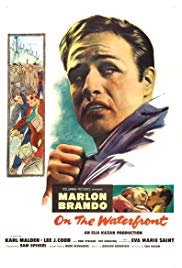

While the vast majority of labor unions are beneficial organizations which represent their members and look out for their welfare, there has been a problem with organized crime penetration of some unions. The Teamsters Union has had a particular problem with corruption. “On the Waterfront” shows some of the methods employed by corrupt unions to extort money from union members. For example, in the film, workers were required to take out usurious loans they didn’t need (they didn’t work if they didn’t borrow). A favorite trick has been to steal from union pension funds. Periodic government attempts to clean up corrupt unions have met with varying degrees of success.

Why did the people shown in this film tolerate the gangsters? Obviously, they felt intimidated. In addition, there were too many workers chasing too few jobs. This problem is especially severe in low skilled occupations. In times of surplus labor, there is always another guy with a strong back who wants the job.

There have also been problems with boxers (prize fighters) “throwing fights” so that their associates can win bets placed on their opponents. In the movie, Terry Doyle was instructed by his brother to throw a fight so that the gangster boss could win his bets on the other fighter. The loss of this fight ruined Terry’s boxing career. He had to go back to his old neighborhood and work as a longshoreman.

“Tabs” were the name of the medallions qualifying a man to work on any given day . The union decided which longshoreman would get “tabs.” In the corrupt union shown in the film, “tabs” were distributed based on favoritism. In a normal union, they would be distributed based on random selection, seniority, or some other non-corrupt system.

The longshoreman’s union involved in this movie is located in a predominantly Irish neighborhood in New York and dominated by men of Irish extraction. There are also Italian-Americans in this union. Their community had a code that stopped them from reporting information about each other to the police or other authorities. This is one reason why the Waterfront Crime Commission had such trouble gathering information. The film describes the code of silence and Terry’s decision to break that code. The language used by the community is rife with phrases such as “stool pigeon,” “canary,” and “deaf and dumb” which reflect the tradition of silence. This tradition among the Irish may stem from the long and harsh British occupation of Ireland (1166 – 1922). In those centuries many Irish developed a strong distrust of anyone in authority. The organized crime bosses who controlled the union combined this distrust with intimidation to keep their activities from being reported to the authorities. Note that other peoples that have been under occupation by outside powers for long periods of time developed similar codes of silence which were also abused by criminal syndicates. A prime example is Sicily and the Mafia. These two cultural influences worked together in the union local shown in the movie.

“ON THE WATERFRONT” AND THE RED SCARE OF THE LATE 1940S AND EARLY 1950S

Elia Kazan, the director of this film, was briefly a member of the Communist party in the 1930s. Like many in Western Europe and America, he joined the party because he agreed with the social reforms it advocated but he rejected Communism after learning about Stalinist excesses in Russia.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, extreme right-wing idealogues had become powerful in the U.S. Congress. They sought to punish people with left-wing political beliefs by associating them with the Communist party. The redbaiters said that they were trying to purge communists from the government and from positions of influence in society. However, their charges were almost always undocumented and false. In reality, they were using the fear of communism for their own political and economic gain by grossly exaggerating the influence of communists in the U.S. In the process they ruined the careers and damaged the lives of many innocent Americans whose only offense was to disagree with them politically.

The House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and a Senate investigating committee, chaired by the now disgraced Joseph McCarthy, were controlled by the redbaiters. If people were revealed as having formerly been members of the Communist Party (at the time a legal political organization), or if they had attended left-wing political rallies or engaged in liberal political activities, their employers were pressured to fire them and they were placed on blacklists so that they could not work. However, if they agreed to testify before the investigating committees, publicly recant their beliefs, and give the names of other people who participated in left-wing political activities, they did not lose their jobs.

Many people, including Kazan’s friend, the great American playwright Arthur Miller, refused to cooperate with the HUAC and McCarthy’s Senate investigating committee. Their position was that the First Amendment prohibited the government from enquiring into the political beliefs or the legal political activities of American citizens. When they refused to testify on First Amendment grounds, they were charged with contempt of Congress and many were jailed.

The Hollywood studios caved in to the redbaiters and enforced blacklists of writers, directors and actors, based solely on their political beliefs and their refusal to cooperate with the Congressional committees. As a result many talented directors, writers and some actors were prevented from working for many years. When Kazan’s turn came and he was called to testify before the HUAC, the Hollywood studios put pressure on him to testify. He agreed to do so.

Kazan’s actions in cooperating with the HUAC and the McCarthyite redbaiters were bitterly resented by many. The playwright Arthur Miller provides an unforgettable description of a conversation with Kazan, in which the director unsuccessfully sought Miller’s approval for his decision to testify. See pages 332 – 335 of Timebends, Miller’s autobiography.

Miller, when he was called in front of the HUAC, refused to testify on First Amendment grounds. This stand, which is now acknowledged as more principled than Kazan’s decision to name names, earned Miller a prosecution and conviction for contempt of Congress. Fortunately, the conviction was overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court and Miller didn’t have to spend time in jail.

“On the Waterfront” was an unsuccessful attempt by Kazan to justify his actions in testifying. In the film he equated testifying before an investigating committee about illegal activities in a labor union with testifying about the political activities of citizens. Arthur Miller responded with the play “A View from the Bridge” which is also set among dock-workers. In the play, which later became a motion picture, the main character informs on two illegal immigrants based on self-serving motivations.

The judgment of history has condemned Joseph McCarthy, the HUAC, the redbaiters, and those who, like Kazan, cooperated with them. The bitterness about Kazan’s decision to testify lasted for decades. As late as 1999, when the Academy of Motion Picture Artists gave the director a lifetime achievement award, there was a storm of protest.