RABBIT-PROOF FENCE

SUBJECTS — World/Australia;

SOCIAL-EMOTIONAL LEARNING — Human Rights; Courage;

MORAL-ETHICAL EMPHASIS — Respect; Respect.

AGE: 10+; MPAA Rating — PG (for emotional thematic material);

Drama; 95 minutes; Color.

There is NO AI content on this website. All content on TeachWithMovies.org has been written by human beings.

SUBJECTS — World/Australia;

SOCIAL-EMOTIONAL LEARNING — Human Rights; Courage;

MORAL-ETHICAL EMPHASIS — Respect; Respect.

AGE: 10+; MPAA Rating — PG (for emotional thematic material);

Drama; 95 minutes; Color.

TWM offers the following worksheets to keep students’ minds on the movie and direct them to the lessons that can be learned from the film.

Film Study Worksheet for a Work of Historical Fiction and

Worksheet for Cinematic and Theatrical Elements and Their Effects.

Teachers can modify the movie worksheets to fit the needs of each class. See also TWM’s Historical Fiction in Film Cross-Curricular Homework Project.

During the first half of the 20th century, the government of Australia took children of mixed Aboriginal/white origins from their homes, trained them in boarding schools, and sent them to work in white communities. Most of the children never saw their parents again. The purpose was to break up mixed families, teach the children “civilized” ways, and absorb them, culturally and genetically, into white society. This movie is the true story of three young girls who ran away from boarding school at the Moore River Settlement. Living off the land and on handouts, they eluded trackers and the police for months.

Selected Awards:

2002 Australian Film Institute: Best Film, Best Sound, Best Original Score; 2002 Australian Film Institute: Best Supporting Actor, Best Cinematography, Best Costume Design, Best Direction, Best Editing, Best Production Design, Best Screenplay Adapted from Another Source.

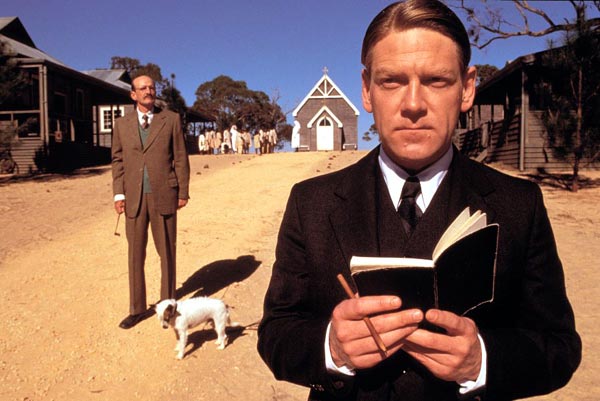

Featured Actors:

Evelyn Sampi as Molly, Tianna Sansbury as Daisy, Laura Monaghan as Gracie, David Gulpilil as Moodoo, Ningali Lawford as Molly’s mother, Myarn Lawford as Molly’s grandmother, Deborah Mailman as Mavis, Jason Clarke as Constable Riggs and Kenneth Branagh as A. O. Neville.

Director:

Phillip Noyce.

“Rabbit-Proof Fence” will acquaint children with a shameful chapter of Australian history and invite comparisons to the experiences of other countries, including the United States. For example, the Australian policies bore a striking resemblance to the treatment of Native American children by the U.S. Interesting comparisons can be drawn to the modern day reaction of Australia and the U.S. to these legacies. Other comparisons can be drawn between the Australian government’s plan to eliminate half-caste Aborigines through dilution of their Aboriginal genes and the Nazi policies (during the same time period) of eliminating minority populations (Jews, gypsies, political opponents, etc.) through extermination or, in the case of the Poles, limiting their calorie intake to a level that did not permit reproduction. Other comparisons can be made between the Australian policies and recent attempted genocides in Rwanda and ethnic cleansing in the Balkans.

None.

After watching the movie read with your child some of the quotes set out in the Helpful Background section. Then ask and help your child to answer the Quick Discussion Question.

The movie paints an accurate picture of the treatment of half-caste Aboriginal/white children by the Australian government from 1915 to 1970. As portrayed in the film, the “biological absorption” philosophy was developed and enforced by the Chief Protector of Aborigines, A. O. Neville. Below are selections from the Western Australia Section of “Bringing them Home”, a report by the Australian Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission.

Protests from non-Indigenous people in the south about the presence of Aboriginal camps on the edges of towns led the government to … establish isolated self-contained “native settlements” run by the government. Chief Protector A. O. Neville who was appointed in 1915 and who remained in the position until 1940, was firmly committed to the new plan. Neville saw the settlements as a means of integrating children of mixed descent into the non-Indigenous society. They were to be physically separated from their families on the settlements, receive a European education, be trained in domestic and stock work and then sent out to approved work situations. Between jobs, they would return to the settlements. Neville theorized that this process would lead to their acceptance by non-Indigenous people and their own loss of identification as Indigenous people.

[The Report is interspersed quotations from evidence received by the Commission throughout the narrative. This is an example of one of the quotations.] “My [wife’s] father died when she was eleven, so Rose was left an orphan, and was placed in the New Norcia home for Aboriginal girls … Rose left her life in New Norcia mission when she turned fourteen, to work as a housemaid. But before she could go out to work, she had to come to the Moore River Native Settlement … Rose had no trouble being placed in service to a white woman. In between, she had to return to the settlement … All those who went out to work had to return to Moore River when their terms of employment were finished: to do otherwise meant to be hounded by the authorities and made to return. Again, no options! No choice!” (van den Berg 1994 pages 88-89)

[Previously, the government had tried to attract Aborigines to “missions” at which they were permitted to maintain much of their traditional lifestyle. Neville started by taking control of one mission, converting it into a “settlement,” and expanding its size so that it would be self-supporting.] … In 1918 a second settlement was opened, at Moore River. In the north, too, Neville wanted to take control of the missions and turn them into self-supporting cattle stations. Moola Bulla in the Kimberley was his model. It had opened in 1910 as a ration depot and government-run cattle station. It was intended to be an alternative to the more expensive option of imprisoning large numbers of Aboriginal people for cattle spearing as well as `raising beef to feed them and … training men for work on the stations’….

There would be considerable savings to the government as it would no longer have to subsidize the missions. Neville was concerned that “A large number of natives and half-castes are growing up in idleness instead of being employed on the various stations in the Northern portions of the State … scores of the children are growing up without any prospect of a future before them, being alienated from their old bush life, and rendered more or less useless for the condition of life being forced upon them” (A. O. Neville quoted by Jacobs 1990 on pages 77-78)

… On purchasing Munja [a new settlement] Neville commented that “the purpose of establishing the stations was to pacify the natives and accustom them to white man’s ways and thus enable further settlement” (quoted by Kimberley Land Council submission 345 on page 11)….

Indigenous families did not willingly move to these settlements. In Southern Australia, most were able to find employment in their local area, receiving wages which were preferred to the payment in kind offered at settlements. The living conditions at the settlements were not significantly better yet they were highly regulated. The parents rightly feared that their children would be placed in segregated dormitories if the family moved to a settlement.

“We were locked up at night. All the boys, young girls. Married girls and women what had no husbands and babies, they had one room. Another dormitory was for young girls had no babies. But we was opposite side of that, see? The boys’ dormitory. I’m not going to complain about it because, you know, I survived. A lot of kids died. Depression time it was pretty hard.” Confidential evidence 333, Western Australia

The missions attracted families whose children would otherwise be taken from them. [But …]

Even when at the mission the children still took every precaution. The women discussed in the raffia room what to do with their children if the police should take them on the hop. Where could they hide them? – inside the cupboard perhaps? … The children however took matters into their own hands. They continually kept their ears cocked for horses’ hooves. [In 1926] came a visit from A.J. Neale, new manager of Moore River Settlement, representing the Aborigines Department. Dicky Wingulu, Doris’s tribal father, talked to Mr Neale and pleaded for his little girls that they not be sent away to Moore River. Finally he persuaded Mr Neale that Mount Margaret would be a good place to send them, as he had heard they were starting a school. (Morgan 1991 pages 83 and 94)

As in the past, to compel people to move the Aborigines Department refused rations or other assistance to people living away from the settlements. In response to complaints from local police about the camps on the outskirts of non-Indigenous towns, Indigenous people were “rounded up” by police and sent to the settlements. Aborigines convicted of alcohol-related offences were also sent to Moore River for their `rehabilitation’. Between 1915 and 1920 at least 500 people, about a quarter of the Indigenous population in the south, had been removed to settlements. Moore River expanded quickly. In January 1919 there were 19 inmates at Moore River, in June 1919 [there were] 93 inmates, by June 1927 [there were] 330 inmates and by 1932 500. (Choo 1989 page 45)

In the north, travelling inspectors kept a watch for mixed descent children on pastoral stations and in communities. Warrants were then prepared for their forcible removal to the government settlements in the north or far south to Moore River.

Labor as a Domestic

Children of mixed descent were sent out from the settlements to work at the age of 14. A large proportion of young women returned pregnant. Though annoyed that the burden of maintaining these children fell upon the government, Neville did not feel that the high rate of pregnancies reflected adversely on his department’s policies.

“The child is taken away from the mother and sometimes never sees her again. Thus these children grow up as whites, knowing nothing of their own environment. At the expiration of the period of two years the mother goes back into service so that it doesn’t really matter if she has half a dozen children.” (quoted by Choo 1989 on pages 49-50)

By the 1930s Neville had refined his ideas of integrating Indigenous people into non-Indigenous society. His model was a biological one of “absorption” or “assimilation”, argued in the language of genetics. Unlike the ideology of racial purity that emerged in Germany from eugenics, according to which “impure races” had to be prevented from “contaminating” the pure Aryan race, Neville argued the advantages of “miscegenation” between Aboriginal and white people.

The key issue to Neville was skin colour. Once “half-castes” were sufficiently white in colour they would become like white people. After two or three generations, the process of acceptance in the non-Indigenous community would be complete, the older generations would have died and the settlements could be closed.

Neville claimed that the settlements prepared Indigenous children to be “absorbed” into non-Indigenous society. He argued that for the absorption process to work properly his powers needed to be extended to all children with any Indigenous background. The grandiose nature of his “vision” contrasted starkly with the reality of life in the chronically under-funded settlements.

“I visited the Moore River Settlement several times [in the 1930s]. The setting was a poor one with no advantage for anyone except isolation. The facilities were limited and some of them were makeshift. The staff were inadequate both in numbers and qualification. The inmates disliked the place. It held no promise of a future for any of them and they had little or no satisfaction in the present. It was a dump.” (Hasluck 1988 page 65)

For the full report, see Bringing them Home: Report of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families.

The half-caste children removed from their homes are known in Australia as the “Stolen Generations.” Some of the scenes in the film appear to have been taken from the Report. Here is an example of a scene described in the report which is analagous to a scene in the movie.

I was at the post office with my Mum and Auntie [and cousin]. They put us in the police ute [utility vehicle] and said they were taking us to Broome. They put the mums in there as well. But when we’d gone [about ten miles] they stopped, and threw the mothers out of the car. We jumped on our mothers’ backs, crying, trying not to be left behind. But the policemen pulled us off and threw us back in the car. They pushed the mothers away and drove off, while our mothers were chasing the car, running and crying after us. We were screaming in the back of that car. When we got to Broome they put me and my cousin in the Broome lock-up. We were only ten years old. We were in the lock-up for two days waiting for the boat to Perth. Confidential evidence 821

Snatching the babies as shown in the film

During the latter part of the 20th century, white Australians began to apologize for the treatment of the “stolen Generations.” A day was set aside as, National Sorry Day, on 26 May 1988. There is a National Sorry Book which white Australians sign which states:

By signing my name in this book, I record my deep regret for the injustices suffered by Indigenous Australians as a result of European settlement and, in particular, I offer my personal apology for the hurt and harm caused by the forced removal of children from their families and for the effect of government policy on the human dignity and spirit of Indigenous Australians.

I would also like to record my desire for Reconciliation and for a better future for all our peoples. I make a commitment to a united Australia which respects this land of ours, values Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander heritage and provides justice and equity for all.

See, Sorry Day.

It is beyond the scope of this Learning Guide to provide a full description of Native American boarding schools in the U.S. However, we do know that during the 19th and 20th centuries, Native American children were placed in boarding schools far from their homes. The purpose was to educate and “civilize” American Indian youth and teach them the ways of white culture. In most of these boarding schools, children struggled with loneliness and fear. They were deprived of the support of their families and their tribal cultures. Many died from diseases such as influenza, tuberculosis, and measles. Native American children have committed suicide in numbers far above a normal rate. Often, children sent to boarding schools had trouble re-integrating into Native American society when they returned to the reservation.

The purpose of the best of these schools was described by the founder of the first Native American boarding school, Capt. R. H. Pratt:

We can end their existence among us as [a] separate people by a broad and generous system of English education and training, which will reach all the 50,000 children and in a few years remove all our trouble from them as a separate people and as separate tribes among us, and instead of feeding, clothing and caring for them from year to year, put them in condition to feed clothe and care for themselves. Our experiences in many individual cases in the last few years make it evident that not only may we fit him [the Native American] to go and come and abide in the land where ever he may choose, and so lose his identity. Origin and History of work at Carlisle.[ The American Missionary./ Volume 37, Issue 4, April 1883]

Like the boarding schools in Australia, one of the purposes of the boarding schools for Native Americans was to break up their families and eliminate tribal influence. (Pratt’s motto was “kill the Indian, save the child.”) The cultural values of white society were stressed. Students were not permitted to speak their own language and were forced to speak English. They were given English names and not permitted to use the names given to them at birth. Their hair was shorn. They were not permitted to eat traditional Native American foods. They were required to wear uniforms. They were taught practical skills and some were placed as apprentices with local families. We are not aware, however, of any announced national policy to dilute the Indian or half-caste gene pool with white blood.

A glimpse of the agony suffered by these children at the deprivation of their cultural identity can be found in the following passage:

Late in the morning, my friend Judewin gave me a terrible warning. Judewin knew a few words of English; and she had overheard the paleface woman talk about cutting our long, heavy hair. Our mothers had taught us that only unskilled warriors who were captured had their hair shingled by the enemy. Among our people, short hair was worn by mourners, and shingled hair by cowards!……

I cried aloud, shaking my head all the while until I felt the cold blades of the scissors against my neck, and heard them gnaw off one of my thick braids. Then I lost my spirit. School Days of an Indian Girl. [Atlantic Monthly./Volume 85, Issue 508, February 1900] The preceding two quotes were taken from Indian Boarding Schools: Civilizing the Native Spirit a lesson plan from the Library of Congress.

On the other hand, the schools provided education and training that otherwise would have been unavailable to Native American children. Some were operated by the tribes themselves or requested and monitored by tribal leaders. Some graduates of these schools excelled, such as Jim Thorpe, the famous Native American athlete who won medals in the 1912 Olympics. Another was Rachel Carlton Eaton, who earned a Phd, published several books on the history of the Cherokees, taught at various colleges, and eventually chaired the history department at Trinity University in San Antonio, Texas. The schools also provided relief from the grinding poverty of the reservations. The association of many tribes together and the friendships that developed at the schools among members of different tribes contributed greatly to “Pan-Indianism.”

The 20th century saw many attempted genocides, including the killings of Armenians by the Turks (1915 & 1916), the Nazi attempt to exterminate European Jewry (1933 – 1945), the attempts by Hutus to exterminate Tutsis in Rwanda (1994) and the attempted ethnic cleansing by Serbs in Kosovo (1999). While that Australian program was cruel and unethical, it was less evil than the genocides because it was aimed at a culture, rather attempting to kill the people who made up the culture. But then, it is an assault on the essence of personal identity to attack a person’s culture, break up the family, and remove a person from his or her community.

In 1948 the United Nations Commission on Human Rights, led by Eleanor Roosevelt, former First Lady of the United States, proposed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It was adopted by the General Assembly that same year. For more on Eleanor Roosevelt, one of the most remarkable women of the 20th century, see Eleanor Roosevelt.

One approach to discussions concerning this film is to have children read sections of Bringing them Home: Report of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families. Selected passages from that Report are set out above. They can be printed out or transferred to a word processing program and made part of a handout. In this way, children will understand that events shown in the film are realistic portrayals of what really happened. Then their attention should be directed to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) adopted by the United Nations in 1948. (Many sections of this document were inspired by the provisions of the United States Constitution and Bill of Rights that protect individual liberties. The U.S. delegation to the conference that wrote the UDHR, headed by former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, was the driving force behind its creation.) The importance of the UDHR cannot be overstated. It is an expression of the best and highest hopes of the human race.

There are a number of ways to use the UDHR with a class. Prepare the class with vocabulary exercises to ensure that they know and understand the words used in the Declaration. See Building Vocabulary Section above. Hand out a copy of the UDHR and ask the students to read it. Or it can be read aloud in class with each student responsible for a section. Ask them, either in discussion or as an essay, to comment on which sections of the UDHR were directly violated by the Australian policy of “biological absorption.” We believe these sections to be: 16(3), 22 and 26(3). Australia’s actions also violated many other provisions of the Declaration, but not as directly as the first three. They include sections 1 – 9, 13(a), 15, 23(1), 25(2), 26(1) and 26(2). You might want to refer to the UDHR as the “Bill of Rights” for the world. It contains many sections based on the Bill of Rights to the U.S. Constitution (the first ten Amendments).

The assignment should differ depending upon the grade level and the sophistication of the students. For example less sophisticated students can be asked to read only the preamble and Articles 1 – 10, 16, 22 and 26 (2) and (3) before writing their essay. More sophisticated students can be requested to read the entire Declaration.

Another exercise that can accompany this movie is a comparison of the actions of the Australian government with the priniciples of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) adopted in 1988. The provisions that directly relate to the “Stolen Generations” are 5, 6.2, 7.1, 8.1, 9.1, 16.1, 29, 30, 34, 37(b) and 37(d). Note that the CRC is much longer and more detailed than the UDHR.

The United States is one of only two countries (Somalia is the other) which have signed but not yet ratified the CRC. Signature indicates an intent to ratify but the Senate has not yet acted. Some 112 other countries have ratified the convention. An interesting class project might be to write to a Senator and support ratification. See American Association of Pediatrics supports Ratification of the CRC. For more on the Convention on the Rights of the Child, see the Unicef Website.

1. [Standard Questions Suitable for Any Film]

2. If a society attempts to integrate a native culture into the dominant culture without losing important aspects of the native culture, how does the society determine what parts of the native culture to keep and what parts of the dominant culture to adopt? Who decides?

Suggested Response:

There is no one correct response to this question and, in fact, for every native culture there is a different balance. The process of adopting dominant cultural values is called assimilation. The ultimate choice is made by each individual but they are subject to strong forces ranging from the attractiveness of certain aspects of the dominant culture to downright coercion.

3. If a society attempts to integrate a minority culture into the dominant culture without losing important aspects of the minority culture, how does the society determine what parts of the native culture to keep and what parts of the dominant culture to adopt? Who decides?

Suggested Response:

See response to preceding question. It has been the observation of the author of this Learning Guide that often in discussions on this topic in the United States too much emphasis is placed on cultural differences between the minorities and there is an inadequate acknowledgment of what the members of various minorities have more in common with the dominant culture. No society wants to be in the “pluralistic” position of countries like Iraq and Turkey (and many others) in which the various subcultures hate and kill each other.

4. Should there be a difference in the response to the two preceding questions. In other words, should the question of assimilation be different for immigrant minorities and native peoples who have become a minority?

Suggested Response:

Arguably, native cultures, which have been conquered and which did not make a voluntary choice to come to the country should have more independence from the dominant culture.

5. Do you think the girls could have really walked all that way?

Suggested Response:

They actually did it; not once, but twice. They were recaptured, sent back to the boarding school, escaped again, and made it home again.

6. Was the scene where the mothers were chasing the car with their children in it realistic? Do you think things like that really happened?

Suggested Response:

It really happened. The official report of the Australian Civil Rights Commission contains an eyewitness account of an incident very similar to the one shown in the movie.

1. Review the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. What was wrong with what the Australians were doing with the half-caste children?

Suggested Response:

See sections 1-10,16, 22 and 26(2) and 26(3).

2. Compare the Australian policy of “biological absorption” with the boarding schools for Native American children established in the U.S.

Suggested Response:

We are not experts in this. However, it appears that there was no systematic effort to dilute the Native American gene pool by isolating the female children into situations in which they would be seduced or raped by white men. There were no systematic efforts to keep the Native Americans away from the reservations after their schooling was complete. Otherwise they appear to be pretty much the same.

Discussion Questions Relating to Ethical Issues will facilitate the use of this film to teach ethical principles and critical viewing. Additional questions are set out below.

(Treat others with respect; follow the Golden Rule; Be tolerant of differences; Use good manners, not bad language; Be considerate of the feelings of others; Don’t threaten, hit or hurt anyone; Deal peacefully with anger, insults, and disagreements)

1. Did the “biological absorption” program treat the half-caste children with respect? Explain the reasons supporting your answer.

Suggested Response:

No. It applied one approach to them with no distinction between those who might benefit from schooling outside the home and those who would not. It did not respect that portion of their heritage that was Aboriginal.

2. Could you design a policy to educate half-caste children living with Aboriginal mothers so that they could advance in the Australian economy and yet respect their Aboriginal heritage?

Suggested Response:

There is no one right answer to this question. It is designed to show how hard a task the Australian government faced.

3. Should the U.S. have a National Sorry Day to apologize to Native Americans or the descendants of African slaves? Would that be better than allowing the Native American to establish gambling casinos all over the country or paying out reparations?

Suggested Response:

There is no one correct answer to this question. A well reasoned response would point out the following. Allowing the Native Americans to make a lot of money by owning casinos and gambling establishments is not an apology. Both the Native Americans and the Aborigines were dispossessed of their land. The whites have no intention of returning this land, so an apology for taking the land while keeping it would be very hypocritical.

4. In what way is Australia’s National Sorry Day and its Sorry Book similar to South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission? How is it different?

Suggested Response:

There is no one correct answer to this question. A well reasoned response would point out the following similarities: In both, the crimes were wide-ranging and an apology from a large segment of the community was required. Differences include the seriousness of the crimes over which the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission had jurisdiction (murder, torture) which were not part of the “biological absorption” policy. Another difference is that the majority in South Africa is black and for the most part was not implicated in the crimes which led to the need for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

1. Write an essay describing the three sections of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights which were directly violated by the Australian government with respect to the “Stolen Generations”.

2. Write a paper answering any one or a group of the Discussion Questions set out above.

3. Give a class presentation, singly or in groups, responding to any of the Discussion Questions set out above or which provisions of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights the Australian government directly violated when it took half-caste Aboriginal/white children out of their families and placed them in boarding schools.

4. Assignments, Projects, and Activities for Use With Any Film that is a Work of Fiction.

Rabbit-Proof Fence by Doris Pilkington is a short book from which the film was taken. It is excellent reading both before or after children see the film.

In addition to websites which may be linked in the Guide and selected film reviews listed on the Movie Review Query Engine, the authors consulted Rabbit-Proof Fence by Doris Pilkington.

This Learning Guide was last updated on December 17, 2009.

* we respect your privacy. no spam here!