THE LIFE OF EMILE ZOLA

SUBJECTS — Literature; World/France; Biography/Zola;

SOCIAL-EMOTIONAL LEARNING — Justice; Talent;

MORAL-ETHICAL EMPHASIS — Trustworthiness; Fairness.

AGE: 10+; No MPAA Rating;

Drama; 1937; 117 minutes; B & W.

There is NO AI content on this website. All content on TeachWithMovies.org has been written by human beings.

SUBJECTS — Literature; World/France; Biography/Zola;

SOCIAL-EMOTIONAL LEARNING — Justice; Talent;

MORAL-ETHICAL EMPHASIS — Trustworthiness; Fairness.

AGE: 10+; No MPAA Rating;

Drama; 1937; 117 minutes; B & W.

TWM offers the following worksheets to keep students’ minds on the movie and direct them to the lessons that can be learned from the film.

Film Study Worksheet for a Work of Historical Fiction and

Worksheet for Cinematic and Theatrical Elements and Their Effects.

Teachers can modify the movie worksheets to fit the needs of each class. See also TWM’s Historical Fiction in Film Cross-Curricular Homework Project.

This movie describes the life of Emile Zola and his pivotal role in the Dreyfus affair. The film is based on the biography Zola and His Time by Matthew Josephson.

Selected Awards:

1937 Academy Awards: Best Picture, Best Supporting Actor (Schildkraut), Best Screenplay; 1937 Academy Awards Nominations: Best Actor (Muni), Best Director (Dieterle), Best Interior Decoration, Best Sound, Best Story, Best Original Score. This film is listed in the National Film Registry of the U.S. Library of Congress as a “culturally, historically or aesthetically significant” film.

Featured Actors:

Paul Muni, Gale Sondergaard, Joseph Schildkraut, Gloria Holden.

Director:

William Dieterle.

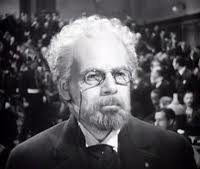

Emile Zola was a crusading journalist, literary innovator, and a man who stood up for what he believed in at great personal cost. In this film, children will be introduced to his life story. The movie also describes the infamous Dreyfus Affair in which the French Army General Staff mistakenly blamed a high-level security leak on its only Jewish member and sentenced him to life in prison on Devil’s Island. When the Army came upon evidence that a mistake had been made, the General Staff refused to acknowledge its error but rather collaborated with the real spy to cover up the mistake. In its treatment of the Dreyfus affair, the movie poses the question: “Is the suffering of one obscure person worth the disturbance of a great country?” Finally, the movie shows how Zola died from a carbon monoxide leak in his stove and provides a basis to explain the danger of carbon monoxide poisoning.

Frank S. Nugent of the New York Times described this film as “Rich, dignified, honest and strong, it is at once the finest historical film ever made and the greatest screen biography ….” There may have been other great biographical films since Mr. Nugent wrote his review, such as “Gandhi” or “Michael Collins“, but they all trace their artistic inspiration to “The Life of Emile Zola.”

MINOR. There is alcohol use and smoking throughout the movie.

Teach your children that justice is one of the most important human rights. People who do not feel that they have been treated justly will not feel an obligation to society to do justice to others. Ask and help your child to answer the Quick Discussion Question. Point out that we all owe a great debt to Zola, a man who was willing to put everything he had worked for on the line for the principle of justice.

Emile Zola (1840 – 1902) founded the school of naturalism in literature, an attempt to describe the world realistically and to deal with the problems of society and of ordinary people. His successes included studies of alcoholism in The Dram Shop, prostitution in Nana, and the life of poor miners in Germinal. In his early years, Zola was not afraid of taking on revered institutions in French society. For example, he exposed incompetence in the Army General Staff in The Betrayal.

In 1894 Alfred Dreyfus (1859 – 1935), a Jewish captain in the French Army, was convicted of spying for the Germans. He was sentenced to life in prison on Devil’s Island, a small desolate bit of land off the coast of South America. Throughout, Dreyfus maintained his innocence. Later, evidence uncovered by Colonel Picquart, head of French Military Intelligence, implicated an officer named Esterhazy. However, in order to prevent embarrassment to the French Army, on orders of the Chief of the General Staff, high ranking army officers forged documents and ordered an acquittal of Esterhazy in a court-martial. Picquart was sent to a desert post and later imprisoned to keep him quiet. The Dreyfus case aroused anti-Semitism throughout France. The Roman Catholic Church, which was part of the French state at the time, supported the conviction.

At the beginning of his career, Emile Zola lived the life of a starving author. His books were unappreciated by the publishers and the public. He was hardly able to eat. But by 1900, after decades of struggle, Zola had finally gained success and affluence. He was considered a great novelist by the French literary establishment. His books sold well. Zola lived well. He knew that if championed Dreyfus’ innocence, he would be tried for criminal libel and that he risked the comfortable life he led. But Zola went ahead. His open letter to the President of France J’Accuse (“I Accuse”) convinced many people in France and throughout the world that Dreyfus was innocent.

As Zola expected, he was accused of criminal libel against the French Army and, like Dreyfus, he was not given a fair trial. Zola was not permitted to establish the truth of his statements as a defense, while Army officers were allowed to testify that Zola’s statements were false. Officers interrupted the proceedings at will. The military packed the courtroom with its supporters who hooted and jeered at Zola’s attempts to defend himself. Military officers were permitted to testify to conclusions without revealing the facts supporting their testimony on the claim that to do so would reveal military secrets. The courthouse was surrounded by hysterical crowds demanding Zola’s conviction, denouncing Zola and Dreyfus as traitors. Zola was pelted with rocks and eggs when he entered or left the courtroom. The jury took less than half an hour to render its verdict of conviction. (The only glaring error in the movie’s portrayal of the trial is that Zola’s address to the court did not occur. The screenwriters took language from “J’Accuse” and made it into a speech.) Zola was sentenced to a year in prison but fled to London to continue the fight there. He was fined 150,000 francs, a huge sum for that time. His wife had to sell their country estate to pay the fine. Zola continued in exile for 18 months returning only after Dreyfus had been tried again on new evidence, convicted but then pardoned by the President of France. Zola died of carbon monoxide poisoning in 1902. It is thought that his enemies stopped up the chimney on his house causing the poisonous gas to accumulate inside. Zola did not live to see Dreyfus completely cleared, which occurred four years after Zola’s death.

In the United States, there are no criminal trials for libel. The rights of citizens and the press to criticize public officials makes it extremely difficult for officials to sue for damages for libel or slander. If the lawsuit against Zola were to have been filed in the U.S., the law as it now stands would have protected him. In order to prevail in a slander or libel case in the United States, a public official must prove not only that the statements against him were false but also that the accuser knew that they were false or acted in reckless disregard for the truth. See New York Times v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254, 265-292 (1964). Zola had studied Dreyfus’ file and had found plenty of evidence supporting the claim that Dreyfus was innocent. So long as Zola did not act in reckless disregard for the truth, he could not have been sued for libel in the U.S. even if it turned out that some of his statements in “J’Accuse” were incorrect.

In 1899, Dreyfus was released from Devil’s Island. Although he was only 39 years of age, his hair had turned white from his experiences there. The French Army was not yet through with Dreyfus. He was subjected to a second court-martial. The evidence against Dreyfus included testimony by a man named Bertillon who asserted that he could tell whether someone was a criminal by measuring parts of that person’s body! Dreyfus was again convicted and sentenced to ten years in prison. World leaders, including U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, demanded that the decision be overturned. Ten days after the conviction, the President of the French Republic pardoned Dreyfus. But it was not until 1906 that Dreyfus was completely cleared and restored to his army rank. In the First World War, still in the French Army, Dreyfus served with distinction and was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel. In 1935, Dreyfus died in his bed in Paris at the age of 75. But old wounds close slowly, it was not until 1995 that the French Army officially admitted that Dreyfus had been framed by a military conspiracy.

Carbon monoxide is a colorless, odorless gas which is a natural byproduct of any combustion process, such as the making of heat by burning wood, coal or gas. In a properly working stove or heater, the gas is drawn up and out of the building through the flue. If there is a leak or obstruction in the flue and the gas penetrates into the space to be heated, the results can be fatal. Zola died of carbon monoxide poisoning. Carbon monoxide poisoning from faulty heating units still kills many people every year.

1. See Discussion Questions for Use With any Film that is a Work of Fiction.

2. Have children find the location of Devil’s Island on a map.

1. What did the concept of “Justice” require the French Army General Staff to do when it realized that a mistake had been made with respect to Captain Dreyfus?

2. The First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States prohibits restrictions on freedom of speech. Could Zola have been prosecuted for libel if he were in the U.S.?

3. France needed an army. To fight effectively, the Army needed to have faith in its leaders. The leaders of the Army claimed that their ability to lead the troops would be compromised if it was found that they had made a mistake in court-martialing Dreyfus. Were they right in this assertion? Why was it so important to prove that Dreyfus was innocent if it risked a crisis in the Army?

4. Zola, in his early years, endured many privations in order to develop his talent for writing. Give three other examples of great writers, artists, dancers or musicians who had to fight for recognition of their talent?

5. Many of Zola’s friends and admirers thought that the Dreyfus Affair was taking Zola’s time away from his writing and the creation of new literary works. Knowing about the body of Zola’s work, do you agree that his campaign for justice for Dreyfus was a departure from his past activities?

Discussion Questions Relating to Ethical Issues will facilitate the use of this film to teach ethical principles and critical viewing. Additional questions are set out below.

(Be honest; Don’t deceive, cheat or steal; Be reliable — do what you say you’ll do; Have the courage to do the right thing; Build a good reputation; Be loyal — stand by your family, friends and country)

1. What would have happened to Dreyfus had Zola lacked the courage to do the right thing? Were there other stakeholders in Zola’s decision such as Zola himself, Zola’s family, all Frenchmen who lived under its system of justice, all French soldiers, all Jewish French Army officers, all French Jews, and all people in the world for whom the French legal system was an example? Should the interests of some or all of these people have been factored into Zola’s decision? If so, how should their interests have affected Zola’s decision?

2. Was Zola being patriotic when he attacked the Army General Staff for incompetence and lying? Would it have been more patriotic to support the army without question? What was the truly patriotic thing for Zola to have done?

3. Was the Censor right in asking Zola to think of the good of the country before he published any more muckraking exposés?

4. This film obviously criticizes the dishonesty of the French Army General Staff. Can you think of any occasions in which our own government has not acted honestly?

Suggested Response:

Some examples for the U.S. government: treaties with Native Americans, Bill Clinton in the Monica Lewinsky scandal, Ronald Reagan and his administration in the Iran-Contra scandal (the administration secretly supplied arms to the contra-guerillas in Nicaragua in violation of a law forbidding this and hid the action by purchasing the arms with money derived from secret sales of arms to Iran); U.S. government treatment of Native Americans; President Eisenhower lying about U-2 flights over Russia; the inflated body bag statistics put out by the U.S. military (at the urging of President Johnson) in the Vietnam War.

(Play by the rules; Take turns and share; Be open-minded; listen to others; Don’t take advantage of others; Don’t blame others carelessly)

5. Would you include as part of this Pillar the obligation to judge others impartially and to make decisions without favoritism or prejudice?

(Additional questions on this topic are set out in the “Justice” section above.)

In addition to websites which may be linked in the Guide and selected film reviews listed on the Movie Review Query Engine, the following resources were consulted in the preparation of this Learning Guide:

This Learning Guide was last updated on December 10, 2009.