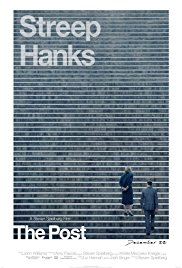

THE POST

SUBJECTS — U.S. 1945 – 1991 & the Press;

SOCIAL-EMOTIONAL LEARNING — Leadership;

MORAL-ETHICAL EMPHASIS — Responsibility.

AGE: 13+; MPAA Rating: PG-13 for language and brief war violence;

Historical Fiction; 2017; 1 hr 56 minutes; Color.

MENU

MOVIE WORKSHEETS & STUDENT HANDOUTS

TWM offers the following worksheets to keep students’ minds on the movie and direct them to the lessons that can be learned from the film.

Film Study Worksheet for a Work of Historical Fiction and

Worksheet for Cinematic and Theatrical Elements and Their Effects.

Teachers can modify the movie worksheets to fit the needs of each class. See also TWM’s Historical Fiction in Film Cross-Curricular Homework Project.

DESCRIPTION

This film is historical fiction about the publication of the Pentagon Papers told from the perspective of the second newspaper to publish excerpts of the document.

SELECTED AWARDS & CAST

Selected Awards:

American Film Institute, AFI Awards: Movie of the Year; 2016 Academy Awards Nominations: Best Picture and Best Actress (Meryl Streep) and a host of other awards nominations.

Featured Actors:

Meryl Streep as Kay Graham; Tom Hanks as Ben Bradlee; Bob Odenkirk as Ben Bagdikian; and Bruce Greenwood as Robert McNamara.

Director:

Steven Spielberg.

BENEFITS OF THE MOVIE

The Post shows an inflection point in U.S. history in which the press exposed decades of government deception about the Vietnam War and the Courts turned back the ever-increasing power of the U.S. Presidency by rejecting prior restraint on the publication of government secrets, except in extreme situations in which there would be “direct, immediate, and irreparable damage to the nation or its people.” (Concurrence of Justice Steward in the Pentagon Papers case.) The film illustrates many of the forces that came together or competed against each other in the struggle over the publication of the Pentagon Papers. In addition, The Post shows a female executive struggling to gain acceptance in a male-dominated world. The movie also touches upon the Vietnam War, a whistle-blower who was willing to go to jail to expose the truth, and the abandonment of the formerly cozy relationship between the press and the government.

Students can watch, discuss, and write about: (1) the most dramatic example of when the people’s right to know what their government is doing prevailed over the interest of government officials in keeping their actions secret; and (2) the interplay of the following forces and institutions in American society: the power of the U.S. Presidency; a free press; the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution; legal restrictions on the publication of top-secret documents; the power and function of the Judicial Branch of the U.S. government; a determined whistleblower concerned for the good of the county; the difficulties encountered by women seeking to exercise power and gain respect in a male-dominated business world; and some of the economics of publishing a newspaper.

POSSIBLE PROBLEMS

The film tells a basically true story. The largest problem with using the movie in education is the filmmakers’ decision to focus on the role of the Washington Post in publishing the Pentagon Papers. The real heroes in the story were Daniel Ellsberg, Aruthur Ochs Sulzberger, Sr. (the publisher of the New York Times), and the reporters from the New York Times. Ellsberg leaked the Pentagon Papers, fully expecting to go to jail for many years as a result of his actions. Sulzberger put his family’s newspaper at risk to publish the documents. Sulzberger and the reporters could have also gone to jail. The New York Times published first and took the greatest risk of government prosecution. The Washington Post played only a secondary role, although the risk was still significant and it did take courage for Katherine Graham to authorize publication. This problem can be turned into a teachable moment about historical fiction. The reason the film doesn’t focus on the New York Times is that there was no Katherine Graham at the Times to provide the human interest component necessary to power a story that would sell tickets at the box office.

HELPFUL BACKGROUND

Arthur Ochs Sulzberger, Sr.

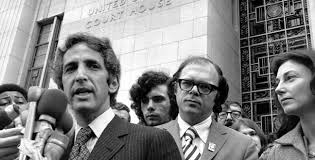

Daniel Ellsberg

HISTORICAL ACCURACY

Here’s some of what’s accurate about the movie, and what’s not.

- In the movie, a Post journalist ferrets out the Pentagon Papers. But firsthand accounts credit the leakers with contacting the newspaper. The leakers contacted many papers figuring that the government couldn’t restrain them all.

- The film shows President Nixon’s furious reaction to the Pentagon Papers’ release. However, Nixon was intially unfazed because the Papers tarnished his Democratic predecessors.

- In a pivotal scene, Robert McNamara tries to stop the Post from running the Papers. In reality, he supported publication.

- In the film, Bradlee regrets having kept a cozy relationship with Kennedy while covering him as a journalist. But the real Bradlee believed he did a prudent job straddling both worlds.

- In the film, the Post’s courageous decision to print inspires other newspapers to follow suit. In reality, other newspapers were hungry to get in on the action and published the Pentagon Papers based on the leakers’ distribution plan.

- President Nixon did not ban the Washington Post from the White House after the newspaper published the Pentagon Papers.

- The Post’s and Katherine Graham’s vulnerability to the companies handling the stock offering is correct. Ketherine Graham said, “We had announced our plans and not sold the stock, so we were particularly liable to any kind of criminal prosecution from the government.”

- The meeting in which Graham said, “Go go ahead, go ahead. Let’s go. Let’s publish.” occurred during the retirement party for an employee of the paper.

- There was conflict over the Style Section which Bradlee had instituted ove the protests of some at the paper.

USING THE MOVIE IN THE CLASSROOM

Introduction to the Movie

Introduce the film by telling the class that this movie shows an inflection point in U.S. history. The direction of the country and the government changed after the publication of the Pentagon Papers; things were not the same as they were before. Ask students, as they watch the movie, to think about what changed and to pay attention to the forces in American society that came together or competed with one another to lead to the publication of the Pentagon Papers.

Students will appreciate this film if they have a basic understanding of First Amendment protections for the Press and the era of the Vietnam War. Check for prior knowledge and make sure that students know at least the following information before showing the film.

Freedom of the Press American political theory holds that the people are the sovereign and that the government should serve the people. However, the government cannot serve the people if it misleads them about its actions. Nevertheless, some secrecy is necessary for governments to function, especially in foreign affairs and in times of war. The question is where to draw the line.

As stated by Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas in his concurring opinion in the Pentagon Papers case:

The dominant purpose of the First Amendment was to prohibit the widespread practice of governmental suppression of embarrassing information. It is common knowledge that the First Amendment was adopted against the widespread use of the common law of seditious libel to punish the dissemination of material that is embarrassing to the powers-that-be. [citation omitted] The present cases will, I think, go down in history as the most dramatic illustration of that principle. A debate of large proportions goes on in the Nation over our posture in Vietnam. That debate antedated the disclosure of the contents of the present documents. The latter is highly relevant to the debate in progress. Justice Douglas concurring in New York Times Co. v. U.S. (1971) 403 U.S. 713, 723–724.

The Vietnam War and the Pentagon Papers — The Vietnam War (1955 to 1974) was the largest defeat of U.S. armed forces in the 20th century. In addition, from 1948 to 1974, the U.S. government deceived the American people about American political and military involvement in Vietnam. During the administration of President Lyndon Johnson (1963 to 1969) and continuing through the administration of Richard Nixon (1969 to 1974) U.S. government officials knew that the war was being lost and that the U.S. was unwilling to commit the money and manpower necessary to prevail. However, in order to save face, U.S. officials did not tell the truth about the war. Tens of thousands of American soldiers and many more Vietnamese died so that various U.S. government officials would not be embarrassed.

One of the chief practitioners of the policy of deception, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, ordered a top secret study of the history of U.S. involvement in Vietnam. The results, some 7,000 pages, called “the Pentagon Papers,” revealed the deception. Daniel Ellsberg, an employee of the Defense Department decided that this story must be told to the American people. Over a period of several months he smuggled sections of the document out of the guarded facility in which he worked, copying the pages at night and returning them the next morning. In 1970, with the war still raging, Ellsburg brought the document to Congressional leaders. When they did nothing to publicize the government’s wrongdoing or take steps to correct the situation, Ellsberg went to the Press, first to the New York Times.

Publication of the Pentagon Papers by the New York Times

The New York Times spent three months fact-checking the materials; making sure that they were accurate and genuine. When they published the documents, the Government demanded that the Times cease publication of the Pentagon Papers. When the Times declined, the government immediately went to court and obtained a restraining order prohibiting further publication

Female Executives in the 20th century

It was extremely unusual for women to lead major corporations in the 20th century. It was said that “A woman’s place was in the home,” While more and more women were joining the workforce, they were not paid equally with men for the same work and they were not permitted to rise to the full level of their potential. The men in power did not think that women had the capability to lead major organizations.

After Watching the Movie

After showing the movie, ask the class to identify the important forces in American society that competed or cooperated to attain the result that the Washington Post became the second newspaper to publish parts of the Pentagon Papers. A partial list is set out below:

- the freedom of the Press protected by the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution;

- laws prohibiting the publication of government documents classified as “secret” or “top secret;”

- the Vietnam War and the failure of the U.S. to prevail in that war;

- the increasing power of the Presidency and the Executive branch of the U.S. Government in the 20th century;

- the conviction of Daniel Ellsberg that the government shouldn’t mislead the people and his willingness to go to jail, if necessary, to get the story out;

- the role of the Judicial Branch of the U.S. government;

- economic pressures on newspapers;

- belief in the 20th Century about “the place” of women in society and that they are not qualified to make important decisions in business or politics; and

- the difficulties encountered by women seeking to exercise power and gain respect in the second half of the 20th century and

Exercise Based on Supreme Court Opinions in the Pentagon Papers Case

The various concurring and dissenting opinions in the case in which the Supreme Court rejected the government’s request for injunctions prohibiting further publication of the Pentagon Papers is an opportunity to teach students about the U.S. government, the role of the three branches of government, the importance of the First Amendment, and the judicial process. TWM has taken the opinion, redacted portions not relevant to those lessons, and removed most citations that would be meaningless to students. Students who read and understand this document will be given a view of the judicial process in action. High school students with strong reading skills and college students can be assigned all of the various concurring and dissenting opinions. Students without strong reading skills can be assigned just one or two of the concurrences or teachers can read several or all of the opinions to them. Click here for a version in Microsoft Word that can be further edited by teachers desiring to use this resource. Click here for a version in pdf.

Before reading the opinion test for prior knowledge or inform the class as to the following:

The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution states: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

“Per Curiam” is from Latin meaning “by the court.” A Per Curiam decision is handed down by an appellate court without identifying the individual judge who wrote the opinion. Per curiam decisions are unusual and have less precedential value than decisions in which a judge writes an opinion that is endorsed by at least four other justices (there are nine justices on the Supreme Court; it takes five justices to make a majority). In this case, the opinion was per curiam because of the need for a speey decison and the fact that there were separate concurring or dissenting opinions from each Justice.

There are three levels of federal trial courts. The general trial court is the District Court. There are 94 federal judicial districts: with at least one in each state, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. There are more than 2700 district court judges. The district courts are organized into 12 regions, called “circuits,” each of which has a court of appeal. There is an additional court of appeal for Washington, D.C. The vast majority of appellate cases are decided by the Courts of Appeal. The U.S. Supreme Court hears relatively few cases each year. It selects the cases that it thinks are most important.

“Certiorari” is a Latin word that means, “to be informed of.” A writ of certiorari is an order by the appellate court to the lower court to bring the case before the appellate court. It is used when the appellate court has discretion about whether or not to hear the appeal. The vast majority of cases heard by the U.S. Supreme Court are taken up on the discretionary writ of certiorari.

A “concurring opinion” is written when one or more justices agree with the result of the case, either to affirm the lower court or to reverse the lower court decision, but their reasons are different from those given by the majority. In the Pentagon Papers case, the per curiam decision does not set out a detailed analysis of the reasons for the decision. The justices used their concurring opinions to explain their reasons for voting the per curiam decision. .

A dissenting opinion is given when a justice disagrees with the decision of the court. It explains his or her reasons for the disagreement.

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. served on the Supreme Court from 1902 until 1932. He is one of the most respected justices to serve on the Court. He is often quoted as an authority, even when he wrote in dissent. Charles Evans Hughes served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court from 1910 to 1916, then U.S. secretary of state from 1921–25 and then as the 11th Chief Justice of the Supreme Court from 1930 to 1941. He, too, is a respected jurist and his opinions are frequently cited by courts as authority for their decisions.

Examples of How Social Customs Change in Little Ways that Can Make a Big Difference

From an Interview of Katherine Graham by Terri Gross

GROSS: You write that early on after taking over The Post, you were encumbered by a deep feeling of uncertainty and inferiority and the need to be – to please and to be liked. You say, I was unable to make a decision that might displease those around me. How did that affect your decision making early on and your interactions with the staff?

GRAHAM: Oh, it got in my way a lot, but it’s a very – lot of – it tends to be female baggage, and it still is to some extent. But it was much worse then. The way it affected my performance is that I couldn’t say, I’ve listened to everybody, and now I think we ought to do this. I had to get everybody to agree to whatever it was. And if everybody didn’t agree, I’d go around, begging them to see my point of view. And it was just a very poor way to be a leader.

GROSS: Suddenly, you were – your social circle expanded, but that circle was really pretty similar to the one you’d had before with your husband. But now, instead of being the wife, you were the publisher in that circle. How did that change your behavior in that circle? And was there an uncomfortable transition (laughter)?

GRAHAM: I think it was very gradual because I was used to the people I was relating to. I just gradually grew used to it. And I realized that I was going to be conspicuous because I had the job I had. At one point, I was at my friend Joe Alsop’s for dinner, and I had been used to the women and the men parting company after Washington dinners, while the men talked about issues and the women went and powdered their nose and discussed their households.

And at one point, I suddenly realized that I’d been working all day, that I’d been involved in an editorial lunch with somebody who was in the news and that I’d been working and that now I was being asked to go in the other room with the wives. And I said to Joe, who was a good friend, I hope you won’t mind if I slip out of here because the paper comes, and I really can use the time better than going into that room with the wives.

And he said, oh, darling, you can’t do that. And I said, sure I can. I mean, it’s just I don’t want to use my time like that, Joe. And so he was so upset that he made me stay. And he broke up the segregation. And then it broke up all over Washington. So that was an instance where, I guess, suddenly I realized that I was in the working world and that I didn’t have to do those things.

How Katharine Graham Defied A Federal Judge To Publish The Pentagon Papers Interview by Terri Gross, The New Yorker, 12/15/17

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

After watching the film, engage the class in a discussion about the movie.

Note to Teachers: The sophistication of class discussion will increase dramatically if the class has read any of the concurring or dissenting opinions in the Supreme Court’s Pentagon Papers decision. In addition, an excellent way to conduct class discussion is for teachers to at least suggest and require students to rebut arguments contrary to those taken by the students. For example, students who believe that the decision was correctly decided can be asked about the points made in Justice Harlan’s dissent. Thus, TWM suggests that before the class teachers read and familiarize themselves with the reasons given by the various justices for and against the per curiam decision. See Read Excerpts of the Supreme Court Opinions in the Pentagon Papers Case, above.

1. What is the legacy of the government deception surrounding the Vietnam war?

Suggested Response:

Perhaps it was best expressed by Don Rumsfeld an aid to Richard Nixon who later served Presidents Gerald Ford and George W. Bush as Secretary of Defense: There is a tape of H.R. Haldeman, Chief of Staff to Richard Nixon, telling the President:

Rumsfeld was making this point this morning… To the ordinary guy, all this is a bunch of gobbledygook. But out of the gobbledygook comes a very clear thing…. You can’t trust the government; you can’t believe what they say; and you can’t rely on their judgment; and the – the implicit infallibility of presidents, which has been an accepted thing in America, is badly hurt by this, because It shows that people do things the president wants to do even though it’s wrong, and the president can be wrong.

Note that Haldeman was a major participant in the Watergate Scandal. He was convicted of perjury, conspiracy, and obstruction of justice and given an 18-month prison sentence.

2. Do you agree with the Supreme Court decision in the Pentagon Papers case that the government must show clear injury to the national defense before the Courts will enter prior restraint orders that prohibit the publication of top-secret government information?

Suggested Response:

There is no one correct response to this question. Note, however, that the general consensus of constitutional scholars is that the case was rightly decided.

An alternative formulation of the question, is “Which of the concurring or dissenting opinions do you agree with? State your reasons.”

3. What are the responsibilities of newspaper publishers when they are provided with secret or top-secret government information? How do you suggest that they fulfill these responsibilities? Put yourself in the position of an editor of a paper who is given an important top-secret document that will influence the public debate on an issue? What would you do?

Suggested Response:

[Note to teachers: See the dissenting opinions in the Pentagon Papers case.] There are options other than to publish or not to publish. One is to go the government, inform them that you have the document and then ask them whether there is any part of the document the disclosure of which would endanger the national security or the life of any individual and to explain their reasoning. You could then redact (cross-out so that it cannot be read) certain parts of the document or try to come to some agreement with the government about which parts can be published. If not, you can always decide to publsh and the fact that you tried to work something out with the government will be an important factor in your favor.

4. Public disclosure of the Pentagon Papers challenged the idea that the President could do whatever he wanted in foreign affairs without public scrutiny. How has that concept fared in recent years?

Suggested Response:

The response will vary according to current events. Up to the date of the publication of this Guide, August 2018, the Congress has shown no ability to challenge the President’s assumption of complete and uncontrolled power in foreign affairs.

5. Generally, do you believe courts should be required to give any deference to the opinions of members of the Executive Branch? If so, how much deference should a court give? Does the subject area under consideration, whether it is national security or sewer maintenance, make a difference?

Suggested Response:

Courts should give some deference to the opinions of the Executive Branch, especially in areas of national security and foreign affairs. This is the general doctrine of American courts, with some exceptions. However, “deference” doesn’t mean abject surrender.

6. Does the First Amendment permit the courts to enjoin the publication of stories that would present a serious threat to national security?

Suggested Response:

There is no one correct response. During the discussion ask the class to read again the text of the First Amendment. Could it really mean exactly what it says? Justice Brennan’s position was that:

The error which has pervaded these cases from the outset was the granting of any injunctive relief whatsoever, interim or otherwise. The entire thrust of the Government’s claim throughout these cases has been that publication of the material sought to be enjoined ‘could,’ or ‘might,” or ‘may’ prejudice the national interest in various ways. But the First Amendment tolerates absolutely no prior judicial restraints of the press predicated upon surmise or conjecture that untoward consequences may result.

7. Justice Douglas wrote, “Secrecy in government is fundamentally anti-democratic . . . ” Do you agree or disagree? What is the basis for this statement?

Suggested Response:

The government is the servant of the people and it is the people who must make the fundamental decisions and through their votes guide the government. However, if people don’t know what the government is doing, they cannot make an informed decision. [This question can be asked using any of the quotes in the Assignment Section below.

8. Is Katherine Graham a good role model for American Women?

Suggested Response:

No, and yes. She inherited the newspaper. Most women will not be so lucky. However, she used her opportunity well and became one of the greatest newspaper publishers in U.S. History. A similar response would relate to this question asked about Hillary Clinton.

See Discussion Questions for Use With any Film that is a Work of Fiction.

MORAL-ETHICAL EMPHASIS (CHARACTER COUNTS)

Leadership

1. How did Katherine Graham show leadership?

Suggested Response:

She listened to various opinions and then she made her decision. Once she made the decision she supported her team in carrying it out.

ASSIGNMENTS, PROJECTS & ACTIVITIES

Any of the discussion questions can serve as a writing prompt. Additional assignments include:

1. Select an important phrase from one of the opinions that you either agree with or disagree with and describe your reasons. Here are some examples:

- Secrecy in government is fundamentally anti-democratic . . . — Justice Douglas

- The official holding of the Court was simple, “Any system of prior restraints of expression comes to this Court bearing a heavy presumption against its constitutional validity. . . . The Government thus carries a heavy burden of showing justification for the imposition of such a restraint.” But I cannot say that disclosure of any of them will surely result in direct, immediate, and irreparable damage to our Nation or its people. That being so, there can under the First Amendment be but one judicial resolution of the issues before us. I join the judgments of the Court. —Justice Stewart

- Nor, after examining the materials the Government characterizes as the most sensitive and destructive, can I deny that revelation of these documents will do substantial damage to public interests. Indeed, I am confident that their disclosure will have that result. But I nevertheless agree that the United States has not satisfied the very heavy burden that it must meet to warrant an injunction against publication in these cases, at least in the absence of express and appropriately limited congressional authorization for prior restraints in circumstances such as these. — Justice White

- The Government’s position is simply stated: The responsibility of the Executive for the conduct of the foreign affairs and for the security of the Nation is so basic that the President is entitled to an injunction against publication of a newspaper story whenever he can convince a court that the information to be revealed threatens ‘grave and irreparable’ injury to the public interest;2 and the injunction should issue whether or not the material to be published is classified, whether or not publication would be lawful under relevant criminal statutes enacted by Congress, and regardless of the circumstances by which the newspaper came into possession of the information. — Justice White

- Since the newspaper could anticipate that the Government would object to the release of secret material, would it have been reasonable for the Times to give the Government an opportunity to review the entire collection and determine whether the agreement could be reached on publication?

- To me, it is hardly believable that a newspaper long regarded as a great institution in American life would fail to perform one of the basic and simple duties of every citizen with respect to the discovery or possession of stolen property or secret government documents. That duty, I had thought—perhaps naively—was to report forthwith, to responsible public officers. This duty rests on taxi drivers, Justices, and the New York Times. The course followed by the Times, whether so calculated or not, removed any possibility of orderly litigation of the issues. If the action of the judges up to now has been correct, that result is sheer happenstance. — Chief Justice Burger.

- It is plain to me that the scope of the judicial function in passing upon the activities of the Executive Branch of the Government in the field of foreign affairs is very narrowly restricted. This view is, I think, dictated by the concept of separation of powers upon which our constitutional system rests. — Justice Harlan

2. Research and write a three-page biography of one of the following major characters in the Pentagon Papers story: Katherine Graham, Daniel Ellsberg, Ben Bradlee, and Arthur Ochs “Punch” Sulzberger Sr.

CCSS ANCHOR STANDARDS

Multimedia:

Anchor Standard #7 for Reading (for both ELA classes and for History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Classes). (The three Anchor Standards read: “Integrate and evaluate content presented in diverse media, including visually and quantitatively as well as in words.”) CCSS pp. 35 & 60. See also Anchor Standard # 2 for ELA Speaking and Listening, CCSS pg. 48.

Reading:

Anchor Standards #s 1, 2, 7 and 8 for Reading and related standards (for both ELA classes and for History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Classes). CCSS pp. 35 & 60.

Writing:

Anchor Standards #s 1 – 5 and 7- 10 for Writing and related standards (for both ELA classes and for History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Classes). CCSS pp. 41 & 63.

Speaking and Listening:

Anchor Standards #s 1 – 3 (for ELA classes). CCSS pg. 48.

Not all assignments reach all Anchor Standards. Teachers are encouraged to review the specific standards to make sure that over the term all standards are met.

LINKS TO THE INTERNET

The best articles on this film:

- Spielberg’s ‘The Post’: Good Movie, Bad History by James C. Goodale, Daily Beast, 12/22/17; [Best general critique of the historical accuracy of the film]

- ‘The Post’ is a fine movie, but ‘The Times’ would have been a more accurate one Roy James Harris, Jr., Poynter 12/21/17;

- Why ‘The Post’ Backlash Misses the Movie’s Real Message by Owen Gleiberman, Variety, 12/27/17 (read until the end – the really great stuff is in the last half of the article;

- The True Story Behind Spielberg’s ‘The Post’; Sara Kettler, Biography, 12/18/17

- The Pentagon Papers Case Ten Years Later by Floyd Abrans, New York Times;

- What The Post Gets Right (and Wrong) About Katharine Graham and the Pentagon Papers by Anna Diamond, Smithsonian.com 12/29/17;

- All the President’s Men Took Katharine Graham Out of the Washington Post’s History. The Post Puts Her Back In. by Jason Bailey, Slate 12/13/17;

- How Katharine Graham Defied A Federal Judge To Publish The Pentagon Papers Interview by Terri Gross, Heard on Fresh Air, 12/15/17;

- ‘The Post’ movie and the Pentagon Papers: Inside the newsroom with former editor Len Downie” by Nicole Carroll, The Republic, 1/12/18;

- Article on Ben Bagdikian in Wikipedia;

- Fact-checking the movie The Post, Oscar nominee for best picture by John Kruzel, Politifact, 2/26/2018;

- by Patrick O’Neil, Extraordinary Conversations 2/5/18;

- David Rudenstine on the History of the Pentagon Papers on C-Span 1/6/18;

Secondary Articles

- Review: In ‘The Post,’ Democracy Survives the Darkness by Manohla Dargis, The New York Times; 12/21/17;

- Fact-checking ‘The Post’: The incredible Pentagon Papers drama Spielberg left out by Michael S. Rosenwald, The Washington Post, 12/23/17; ;

- Interview with Catherine Graham ;

- The Pentagon Papers in the National Archives;

- The True Story Behind The Post MAHITA GAJANAN, Time Magazine, 12/26/17;

- Kenneth Turan reflects on ‘The Post’: How a film critic watches movies about experiences he lived through by Kenneth Turan, LA Times, 12/26/17;

- The Post Is Well-Crafted but Utterly Conventional by Christopher Orr, the Atlantic, 12/22/17;

- Steven Spielberg’s Ode to Journalism in “The Post” Anthony Lane, The New Yorker, 12/17 & 25/2017;

- Pentagon Papers — the complete copy in the National Archives;

- The NSA Leaks and the Pentagon Papers: What’s the Difference Between Edward Snowden and Daniel Ellsberg? by Garance Franke-Ruta, The Atlantic Magazine, 6/15/13;

- The Pentagon Papers Case Ten Years Later;

BIBLIOGRAPHY

See the web pages described in the Links to the Internet Section.