THE WHITE ROSE

In German with English Subtitles

SUBJECTS — World/Germany & WWII;

SOCIAL-EMOTIONAL LEARNING — Rebellion; Courage;

MORAL-ETHICAL EMPHASIS — Trustworthiness.

AGE: 13+; No MPAA Rating;

Drama; 1982; 108 minutes; Color.

There is NO AI content on this website. All content on TeachWithMovies.org has been written by human beings.

In German with English Subtitles

SUBJECTS — World/Germany & WWII;

SOCIAL-EMOTIONAL LEARNING — Rebellion; Courage;

MORAL-ETHICAL EMPHASIS — Trustworthiness.

AGE: 13+; No MPAA Rating;

Drama; 1982; 108 minutes; Color.

TWM offers the following worksheets to keep students’ minds on the movie and direct them to the lessons that can be learned from the film.

Film Study Worksheet for ELA Classes and

Worksheet for Cinematic and Theatrical Elements and Their Effects.

Teachers can modify the movie worksheets to fit the needs of each class. See also TWM’s Historical Fiction in Film Cross-Curricular Homework Project.

This is the true story of a group of German university students who, in 1942 and 1943, published leaflets critical of the Nazi regime. They gained a following among their fellow students but they took too many risks. They were caught and summarily executed.

Selected Awards: Nominated for the 1989 Special Film Award: 40th Anniversary of the Federal Republic of Germany.

Featured Actors: Leno Stolze, Wolf Kessler, Oliver Siebert, Ulrich Tucker, Werner Stocker, Martin Benrath and Anja Kruse.

Director: Michael Verhoeven.

“The White Rose” will acquaint children with two extraordinary people, Hans and Sophie Scholl, and their small group of like-minded friends. It describes World War II on the German home front and Nazi police state tactics. This film is an excellent beginning for an in-depth study of these topics.

MODERATE. This is a tragic story. We are shown the heroine being strapped into the guillotine and hear but do not see, the blade coming down on her neck. There is one brief glimpse of the breasts of one of the girls after making love to her boyfriend.

Before watching the film, make sure that children understand the nature of repression in Germany before and during WWII. For a very brief description see the first paragraph of the Helpful Background section. After the movie, show children the photographs of Hans and Sophie Scholl and their friends contained in the Learning Guide. The major part of your work with this film will be to review with your children the substance of the Helpful Background section and have them read the excerpts of the writings of Hans Scholl contained in that section. Finally, ask and help your child to answer the Quick Discussion Question and as many of the Discussion Questions as possible.

Nazi Germany (along with Stalin’s Russia) developed the modern police state. Freedom of belief, freedom of speech, freedom of association and freedom of the press were eliminated. The only acceptable beliefs were those sanctioned by the ruling party (Nazi or Communist, depending upon which country you were in.) The secret police apparatus was very large and had informants everywhere. Citizen spied upon citizen; co-worker spied upon co-worker; friend spied upon friend; family members spied upon other family members. Punishment for believing something different than permitted by the ruling party or taking action against the ruling party was swift and applied without due process of law. The secret police used summary detentions, often for long periods, corruption and torture. They were universally feared. Membership in officially sanctioned youth organizations was required for young people to get ahead. Adults who wanted to advance in their professions had to join the Nazi party (the Communist Party in Russia).

For reasons still debated by historians and sociologists, the German people did not mount mass protests against the atrocities committed in their name by the Nazis. In this “dark German night”, the actions of The White Rose stand out as one of the few organized groups that sought to oppose the Nazi police state. In 1942, a few students, one professor and their supporters moved from silent disagreement to distributing leaflets strongly critical of the Nazi regime. Led by Hans Scholl and Alexander Schmorell, two medical students in Munich, they also painted “Down With Hitler” on the walls of public buildings. They planned further resistance. All the while they knew that death awaited them if they were caught. Their actions led to additional, but minimal, resistance activities in Hamburg, Berlin and Freiburg.

Hans and Sophie Scholl grew up in a household in which their father reviled Hitler, books that had been banned by the Nazis continued to be read, and anti-semitism was not accepted. From 1933 – 1936 Hans, against his father’s wishes, was actively involved in the Hitler Youth. Identified as a leader by the Nazis, he was appointed to command a squad of 150 boys. His younger sister Sophie was an active member of the BDM, the parallel Nazi youth organization for girls. But there were incidents that caused Hans to become disillusioned with the Hitler Youth. We know of only a few of them. One day when Hans was reading a book that was on the banned list his company leader saw him and ripped the book out of his hands. Hans lost his position as squad leader when a senior Hitler Youth official, an adult, demanded that a 12 year-old member of Hans’ squad give up a banner which the squad had made but which did not conform to the approved banners. As the official tried to forcibly take the banner from the frightened boy, Hans hit the man and knocked him down. Hans was then summarily stripped of his leadership position.

Hans and Sophie’s views about National Socialism came to parallel those of their father. In 1937 Hans joined an anti-Nazi underground youth group. When the Gestapo mounted a crackdown on all youth groups not associated with the Hitler Youth, Hans, his brother and his sisters were arrested. Sophie was released the next day, the two other siblings, Inge and Werner, were kept a week. Hans was imprisoned for three weeks while being questioned by the Gestapo.

After a period of compulsory military service, Hans was admitted to medical school in Munich. There he met Alexander Schmorell, Christoph Probst and several other like minded students. In their long discussions, and watching as the crimes of the Nazis mounted, they finally came to realize that failing to act against the system was, in fact, supporting it. In another development, Robert Scholl, the father of Hans and Sophie, was sentenced to four months in prison for remarks overheard by his secretary. He had called Hitler a “divine scourge” and predicted that, unless the war was stopped, the Russians would be in Berlin in two years.

Sophie Scholl and Soldiers

Sophie Scholl

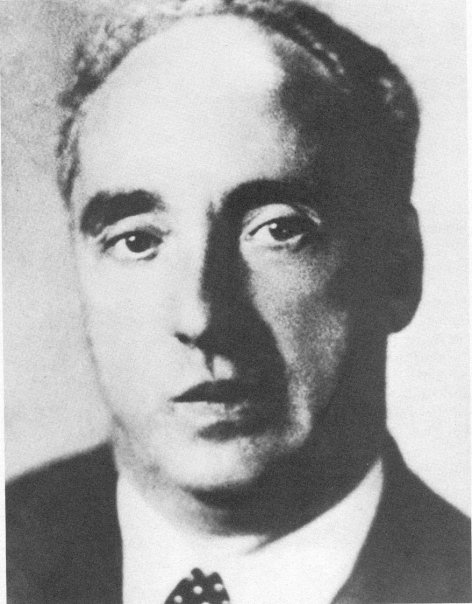

Hans Scholl, Sophie Scholl

and Christoph Probst

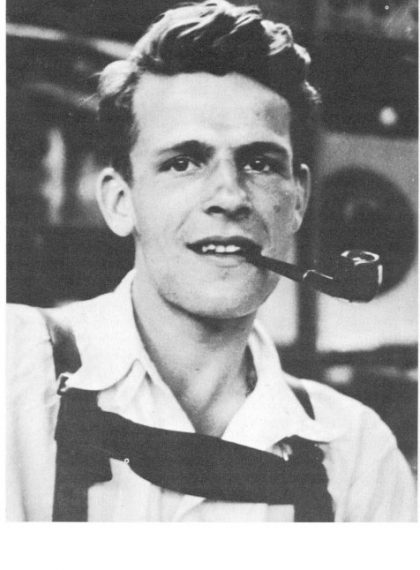

Christoph Probst

Hans Scholl

Hans and his friends printed and distributed six leaflets. They were left at various locations in public places and sent in the mail to random names picked from the phone book. The leaflets were uncompromising in their denunciation of Hitler and the Nazi regime:

The first leaflet stated:

Nothing is so unworthy of a civilized nation as allowing itself to be “governed” without opposition by an irresponsible clique that has yielded to base instinct. It is certain that today every honest German is ashamed of his government. Who among us has any conception of the dimensions of shame that will befall us and our children when one day the veil has fallen from our eyes and the most horrible of crimes — crimes that infinitely outdistance every human measure — reach the light of day… [B]y means of gradual, treacherous, systematic abuse the system has put every man into a spiritual prison. Only now, finding himself lying in feters, has he become aware of his fate. Only a few recognized the threat of ruin, and the reward for their heroic warning was death. … If everyone waits until the other man makes a start, the messengers of avenging Nemesis will come steadily closer; then even the last victim will have been cast senselessly into the maw of the insatiable demon. Therefore every individual, conscious of his responsibility as a member of Christian and Western civilization must defend himself as best he can at this late hour, he must work against the scourges of mankind, against fascism and any similar system of totalitarianism. Offer passive resistance — resistance — wherever you may be, forestall the spread of this atheistic war machine before it is too late, before the last cities, like Cologne [recently heavily bombed by the Allies], have been reduced to rubble, and before the nation’s last young man has given his blood on some battlefield for the hubris of the sub-human….

The second leaflet read, in part:

We do not want to discuss here the question of the Jews, nor do we want in this leaflet to compose a defense or apology. No, only by way of example do we want to cite the fact that since the conquest of Poland three hundred thousand Jews have been murdered in this country in the most bestial way. Here we see the most frightful crime against human dignity, a crime that is unparalleled in the whole of history. For Jews, too, are human beings — no matter what position we take with respect to the Jewish question — and a crime of this dimension has been perpetrated against human beings. Someone may say that the Jews deserved their fate. This assertion would be a monstrous impertinence; but let us assume that someone said this — what position has he then taken toward the fact that the entire Polish aristocratic youth is being annihilated? (May God grant that this program has not fully achieved its aim as yet!) All male offspring of the houses of the nobility between the ages of fifteen and twenty were transported to concentration camps in Germany and sentenced to forced labor, and all the girls of this group were sent to Norway, into the bordellos of the SS! Why tell you these things, since you are fully aware of them — or if not of these, then of other equally grave crimes committed by this frightful sub-humanity? Because here we touch on a problem which involves us deeply and forces us all to take thought. Why do the German people behave so apathetically in the face of all these abominable crimes, crimes so unworthy of the human race? …

… Up until the outbreak of the war the larger part of the German people was blinded; the Nazis did not show themselves in their true aspect. But now, now that we have recognized them for what they are, it must be the sole and first duty, the holiest duty of every German to destroy these beasts.

The last leaflet was entitled “Fellow Fighters in the Resistance”:

Shaken and broken, our people behold the loss of the men of Stalingrad. Three hundred and thirty thousand German men have been senselessly and irresponsibly driven to death and destruction by the inspired strategy of our World War I Private First Class. Führer, we thank you….

We grew up in a state in which all free expression of opinion is unscrupulously suppressed. The Hitler Youth, the SA, the SS have tried to drug us, to revolutionize us, to regiment us in the most promising young years of our lives. …

For us there is but one slogan: fight against the party! Get out of the party organizations, which are used to keep our mouths sealed and hold us in political bondage! …

… The name of Germany is dishonored for all time if German youth does not finally rise, take revenge, and atone, smash its tormentors, and set up a new Europe of the spirit. Students! The German people look to us. As in 1813 the people expected us to shake off the Napoleonic yoke, so in 1943 they look to us to break the National Socialist terror through the power of the spirit. Beresina and Stalingrad are burning in the East. The dead of Stalingrad implore us to take action.

“Up, up my people, let smoke and flame be our sign!”

Our people stand ready to rebel against the National Socialist enslavement of Europe in a fervent new break-through of freedom and honor.

The last leaflet was intended for students at the University and was written by a popular philosophy professor, Dr. Kurt Huber. On February 18, 1943, a Thursday, Hans, age 24, and Sophie, age 21, were seen by a janitor distributing the leaflet. He summoned the Gestapo. In an effort to protect their friends, Hans and Sophie claimed responsibility for all of the actions of the group. They were unable to protect Christoph Probst, another member of The White Rose, from immediate arrest. On the next Monday the three were tried by a “People’s Court,” convicted and summarily beheaded. Hans and Sophie maintained their dignity to their deaths. Hans’ last words “Long Live Freedom!” were shouted just before the knife of the guillotine fell on his neck. Later, the Gestapo was able to pierce Hans and Sophie’s efforts to protect the other members of The White Rose. They were caught and executed or imprisoned. A small group in Hamburg, inspired by the leaflets of The White Rose was also destroyed and its ringleader was executed.

While the film is excellent, the books written about this incident are inspirational. They show the intellectual process by which Hans and Sophie moved from being active in the Hitler Youth organizations to opponents of the regime. See the Bridges to Reading Section below.

Hans and Sophie’s younger brother Werner was in the German Army and died on the Russian Front. The Scholl family lost three of five children during WWII.

Hans Scholl was in a “student company” of the German Army. They were sent to the Russian Front during the summer of 1942 for a “combat internship” to work in hospitals and perform low level medical tasks. This occurred after four of The White Rose leaflets had been distributed. Here are excerpts of several letters and diary entries that Hans wrote while on this trip.

July 27, 1942: Dear Parents, We arrived here [in Warsaw] after a long journey through Germany and Poland. The journey itself was pleasant enough. My friends [including Alex Schmorell] and I had a section to ourselves, and whenever we weren’t asleep, we passed the time conversing intelligently or playing games. We often gazed out of the window for hours on end at the passing countryside — the more so because the endless plains of the East cast their spell over us. There are two salient features here: trees and sky. The farmhouses are thatched with straw, and the farmsteads nestle picturesquely in little birch woods. The sunsets are indescribably beautiful and when the moon comes up and bathes the trees and fields in its magical, silvery glow, one thinks of the Polish prisoners in Germany and understands their boundless love of country.

Warsaw would sicken me in the long run. Thank God we’re moving on tomorrow. The ruins alone are food enough for thought but an American palace towers incongruously into the sky from among shattered walls. Half-starved children sprawl in the street and whimper for bread while provocative jazz rings out across the way, and peasants kiss the flagstones in churches while the bars seethe with unbridled, insensate revelry. The mood is universally doom-laden, but I nonetheless believe in the inexhaustible strength of the Polish people. They’re too proud for one to succeed in striking up a conversation with them. And children are playing wherever you look.

August 4, 1942: Dear Mother, Father’s imprisonment starts today, and today I received your first letter and Sophie’s. Your other letter arrived a week ago.

You can imagine that even though I wasn’t surprised by the news, I didn’t take it calmly. Indignation and turmoil-filled my heart when I read your letter, and it took me a while to calm down again. I did so mainly thanks to your generosity of spirit and all-pervading love. However, I still can’t bring myself to write an appeal for clemency. If I tried, I’d go off the rails….

Father is in for a very hard time at first, as I know too well: starved of contact with the outside world, cooped up alone in a cramped gray cell. He’ll survive, though. Being strong, he’ll emerge from captivity even stronger. I believe in the immeasurable strength of suffering. True suffering is like a bath from which a person emerges born anew. All greatness must be purified before it can exchange the narrow confines of the human breast for a wider world outside.

We shall never escape suffering, not till the day we die. Isn’t Christ being crucified a thousand times every hour, and aren’t beggars and cripples still being turned away from every door, today as always? To think that human beings fail to see precisely what makes them human: helplessness, misery, poverty….

September 18, 1942, Dear Parents: … I’ve developed a passion for riding, and it won’t let go of me. There’s nothing to beat galloping across the plain astride a fast horse, forging your way like an arrow through the head-high steppe grass, and riding back into the forest at sunset, weary to the point of exhaustion, with your head still glowing from the heat of the day and the blood throbbing in every fingertip. It’s the finest delusion I’ve succumbed to, because in a certain sense you have to delude yourself. The men call it “Russian fever,” but that’s a clumsy, feeble expression. It’s something like this: When you see the world in all its enchanting beauty, you’re sometimes reluctant to concede that the other side of the coin exists. This antithesis exists here, as it does everywhere, if only you open your eyes to it. But here the antithesis is accentuated by war to such an extent that a weak person sometimes can’t endure it. So you intoxicate yourself. You see only the one side in all its splendor and glory. I know I haven’t been here long, but I can see what an immense test of endurance a static war is….

A strong wind has been lashing the forest since dawn and shaking the trees, but it’s warm and snug in our dugout. A fire is burning and crackling in the stove, and the gloomy interior is thick with tobacco smoke.

I think of Father a great deal here. And, as one can only in Russia, I often run the entire gamut of my emotions within a few minutes, rising to a shrill pitch of fury and then, just as quickly, subsiding into an expectant, confident, equable frame of mind.

The fall brings so many things with it, among them a desire to burst one’s bonds and fly south with migrant birds to a warmer home. Big flocks of jackdaws are gathering in readiness to fly to where the sun stands overhead at noon, and crows accompany them part of the way.

Diary Entry, July 30, 1942: The plain began in Russia. Before that we were traveling through a gentle morainic landscape. Songs with a youthfully zestful rhythm were awakened in my soul by rolling hills like a frozen sea and, floating above them in the blue sky, cloud-ships that gleamed white in the afternoon sunlight. I was thinking of airy baroque churches and Mozart when, beyond the frontier, there began the broad, boundless plain where every line melts away, where everything solid dissolves like a drop in the ocean, where there’s no beginning or middle or end, where a man becomes homeless and his heart is filled with nothing but melancholy, and his thoughts resemble the ever-changing clouds that float past just as interminably, and his nostalgia resembles the wind that bears them along. All the handholds to which people cling so desperately, like home, native land, or profession, are wrenched off, as it were. The ground gives way beneath your feet, and you fall and go on falling, and just as you’re wondering where to, and all your faithful companions are deserting their broken master because they’ve nothing left to hope for, you unexpectedly and gently land, as though wafted there by angels, on the soil of Russia: on the plain that belongs to God alone and his clouds and winds.

God is closest when home is farthest, hence the young person’s desire to go forth, leaving everything behind, and wander aimlessly until he has snapped the last thread that held him captive — until he stands confronting God in the broad plain naked and alone. He will then rediscover his native soil with eyes transfigured.

Diary Entry: the next day, July 31, 1942: Gray clouds are hovering over the plain. The horizon looks like a silver ribbon dividing earth and sky. On earth, colors glow undiminished through the thin drizzle in every shade of brown, yellow, and green. When a shaft of light pierces the overcast in the far distance, an expanse of land gleams like a mirror, and the earth laughs like a child with a smile breaking through the tears in its eyes

How splendidly the flowers are blooming on this railroad embankment! As if all had assembled so that no color should be missing, they bloom here with gentle insistence — everywhere: alongside ruined buildings, gutted freight cars, distraught human faces. Flowers are blooming and children innocently playing among the ruins. O God of love, help me to overcome my doubts. I see the Creation, your handiwork, which is good. But I also see man’s handiwork, our handiwork, which is cruel, and called destruction and despair, and which always afflicts the innocent. Spare your children! How much longer must they suffer? Why is suffering so unfairly meted out? When will a tempest finally sweep away all these godless people who besmirch your likeness, who sacrifice the blood of countless innocents to a demon? The whole world is bright again, for as far as the eye can see, after this rain.

That fall, Hans and Alexander returned to Munich where they again took up their studies and the work of The White Rose. The beauty of their souls was snuffed out by the dictator’s guillotine.

1. See Standard Questions Suitable for Any Film.

2. Both Napoleon and Hitler lost vast armies attempting to conquer Russia. Neither was able to recover and both were eventually overthrown in large part because of their losses in Russia. Can you describe why Russia is so difficult to conquer?

Suggested Response:

(1) Russia is very big and the winters are incredibly cold; colder than anything experienced in Germany or France. (2) The Russians in both instances followed a scorched earth policy: cities and villages were burned; factories were moved or destroyed; and stocks of food and grain were moved or burned. There was not enough food to sustain the invading troops. When Napoleon reached Moscow, the capital of Russia, he found that the Russians had burned the city to the ground. (3) The Russians are valiant and determined fighters, especially when defending their homeland.

3. Should Hans have permitted his sister Sophie to become involved in The White Rose? Both he and Sophie knew the risks. Should they have thought of the grief their parents would have felt if they were both caught? Shouldn’t Sophie have been kept insulated from activity in The White Rose so that their parents would have lost only one child and not two if the resistance group was discovered?

Suggested Response:

There is no one right answer to the question. A good exchange would be as follows: At some point personal considerations no longer prevail. When the state becomes bent on murder and human rights violations, for example, it is the responsibility of every citizen to resist. How could Hans have denied Sophie the right to participate in a fight necessary to be an ethical human being? The counterargument is that the chances that The White Rose would mount a meaningful resistance were very small given the forces arrayed against them. Sophie’s life was sacrificed for nothing. The rebuttal is that one can say that about the beginning of every revolutionary movement, including the American Revolution and the French Revolution, the two revolutions that brought democracy to the world. If no one takes the first, very dangerous and most likely futile steps, nothing will ever change. In addition, Sophie’s life wasn’t sacrificed for nothing. By working with The White Rose, she redeemed her soul under any definition of that concept. Finally, Sophie and Hans have left us with a story of courage and commitment that serves as a model for us and for generations to come.

4. What did the characters in the film mean when they referred to the fact that the paint that they used to write “Down with Hitler” on public buildings was “pre-war” paint and therefore difficult to scrub off the walls?

Suggested Response:

For both the Allied and the Axis powers, WWII was a total war in which all of the resources of society were diverted into the war effort. Thus, the chemicals used to make paint adhere strongly to walls were needed by the armed forces and were not available for civilian use. The paint sold to civilians during the war lacked these materials and could be easily removed. We don’t know specifically about paint but there were similar shortages in the U.S. and Britain.

5. What does the Second Leaflet tell us about the claims of individual Germans after the war that they had not known about the concentration camps and the attempt to exterminate the Jews, political opponents of the Nazis, the Roma and others?

Suggested Response:

It is clear that the claim that many or most Germans didn’t know what was going on in the camps was untrue. We don’t know how The White Rose obtained the information reported in this leaflet. The Scholls listened illegally to news reports from the British Broadcasting Corporation. Perhaps they learned of the atrocities from the BBC, but the Scholls had no special access to information. The facts known to them about the concentration camps were available to others as well.

1. If you had lived in Germany during the Second World War would you have had an obligation to resist the Nazis? Would you have complied with it like Oskar Schindler and the Scholl’s or would you have kept quiet?

Suggested Response:

Every person living in Germany during the time when the German government sought to imprison and kill people for their ethnicity or political beliefs, religious beliefs or mental illness or retardation had an obligation to resist. One cannot stand by and watch his fellow human beings be imprisoned or killed by his own society and keep still.

2. What is the obligation of a citizen in a country which is prosecuting a war that he or she feels to be bad policy? For example, there were many Americans who opposed our entry into World War I. But once war had been declared, they supported the war effort because they felt that it was the right of the majority to decide to go to war and that once the decision was made, as members of society, they were bound to support the war effort. [If students are interested in the question, read to them the description of the position of William Jennings Bryan on WWI in the Learning Guide to “Inherit The Wind”.] What about the millions of Americans who protested against the Vietnam War while it was going on? Was that position justified?

Suggested Response:

There is a difference between participating in the political process before and during a war, which a citizen has the obligation to do, and interfering with troop movements, preventing enlistments, refusing to pay taxes or other activities designed to actually impede the war effort. William Jennings Bryan opposed U.S. entry into WWI, but when the war came, he volunteered for the army. When he was refused enlistment because he was old and sick he made speeches encouraging the many people who idolized him to buy war bonds. He could, consistent with his duties as a citizen, have continued to oppose the war after it had been declared, so long as he did nothing to impede prosecution of the war and fulfilled his obligations as a citizen. However, proponents of wars, including presidents of the United States, have made the assertion that political opposition to their particular war undermined the morale of the troops and hurt the war effort. This is clearly a specious argument because it means that a political decision, the decision to go to war, will trump civil and political liberties. (If this is true, what are we fighting for anyway?) In fact, political opposition to a war which a citizen believes is bad policy is patriotic. Usually it makes that person very unpopular. Sometimes it’s best to pull out of a war (Vietnam is the best example), and if the voices of citizens and politicians advocating that position are silenced, the political process will be harmed. The situation gets still more complicated when opponents of a war come to believe that the war itself is immoral and that they have an ethical obligation to try to interfere with the war effort or to refrain from cooperating in the war effort. When this happens the individual must evaluate the conflict in values: patriotism and civic responsibilities vs. allegiance to ethical and political values.

3. Please see the Quick Discussion Question.

Discussion Questions Relating to Ethical Issues will facilitate the use of this film to teach ethical principles and critical viewing. Additional questions are set out below.

(Be honest; Don’t deceive, cheat or steal; Be reliable — do what you say you’ll do; Have the courage to do the right thing; Build a good reputation; Be loyal — stand by your family, friends and country)

1. What does this film tell us about the limits of patriotism?

Suggested Response:

It tells us that ethics and morality are the limits of patriotism. This is very complicated and each situation must be evaluated on its own merits. People are asked to violate their ethics in war by killing or maiming people, something that in a non-war situation would be unethical. Clearly, German patriotism in WWII did not require Germans to support a government which killed 12 million people in concentration camps. The U.S. placed citizens and resident aliens of Japanese descent into concentration camps but didn’t kill them. It is now recognized that this was a violation of their civil and human rights. Did this justify Americans in resisting the war effort during WWII? Few people would say that it did. There is no one right answer to this question in the abstract but it is great for debate.

1. Write a paper on any of the topics described in the Discussion Questions section.

2. Write a paper describing the different mechanisms of oppression, positive and coercive, that were employed by the Nazis on the German population. Use the experiences of Hans and Sophie Scholl as examples.

3. Assignments, Projects, and Activities for Use With Any Film that is a Work of Fiction

The best book about The White Rose was written by Inge Scholl, the sister of Hans and Sophie Scholl. Published in 1947, it was designed for German school children. It has been translated and is still in print. It includes the text of the leaflets, the indictments and a narrative. It is suitable for good readers from approximately age 12 and up. The book is entitled The White Rose, Munich 1942 – 1943. A full account of The White Rose by two historians is entitled Shattering the German Night, by Annette E. Dumbach and Jud Newborn. Excerpts of the letters and the diaries of Hans and Sophie Scholl are collected in At the Heart of the White Rose, edited by Inge Jens.

In addition to websites which may be linked in the Guide and selected film reviews listed on the Movie Review Query Engine, the following resources were consulted in the preparation of this Learning Guide:

This Learning Guide was last updated on December 18, 2009.