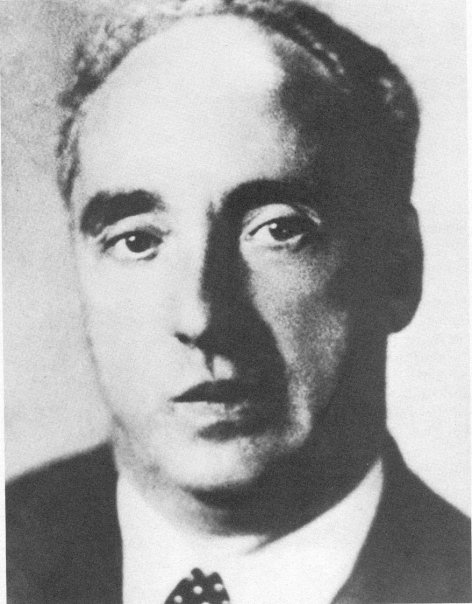

The last leaflet was intended for students at the University and was written by a popular philosophy professor, Dr. Kurt Huber. On February 18, 1943, a Thursday, Hans, age 24, and Sophie, age 21, were seen by a janitor distributing the leaflet. He summoned the Gestapo. In an effort to protect their friends, Hans and Sophie claimed responsibility for all of the actions of the group. They were unable to protect Christoph Probst, another member of The White Rose, from immediate arrest. On the next Monday the three were tried by a “People’s Court,” convicted and summarily beheaded. Hans and Sophie maintained their dignity to their deaths. Hans’ last words “Long Live Freedom!” were shouted just before the knife of the guillotine fell on his neck. Later, the Gestapo was able to pierce Hans and Sophie’s efforts to protect the other members of The White Rose. They were caught and executed or imprisoned. A small group in Hamburg, inspired by the leaflets of The White Rose was also destroyed and its ringleader was executed.

While the film is excellent, the books written about this incident are inspirational. They show the intellectual process by which Hans and Sophie moved from being active in the Hitler Youth organizations to opponents of the regime. See the Bridges to Reading Section below.

Hans and Sophie’s younger brother Werner was in the German Army and died on the Russian Front. The Scholl family lost three of five children during WWII.

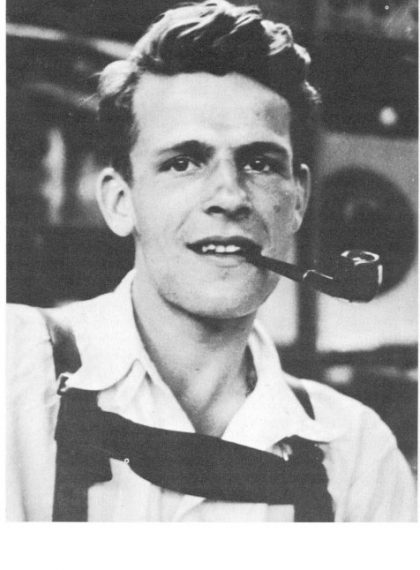

Hans Scholl was in a “student company” of the German Army. They were sent to the Russian Front during the summer of 1942 for a “combat internship” to work in hospitals and perform low level medical tasks. This occurred after four of The White Rose leaflets had been distributed. Here are excerpts of several letters and diary entries that Hans wrote while on this trip.

July 27, 1942: Dear Parents, We arrived here [in Warsaw] after a long journey through Germany and Poland. The journey itself was pleasant enough. My friends [including Alex Schmorell] and I had a section to ourselves, and whenever we weren’t asleep, we passed the time conversing intelligently or playing games. We often gazed out of the window for hours on end at the passing countryside — the more so because the endless plains of the East cast their spell over us. There are two salient features here: trees and sky. The farmhouses are thatched with straw, and the farmsteads nestle picturesquely in little birch woods. The sunsets are indescribably beautiful and when the moon comes up and bathes the trees and fields in its magical, silvery glow, one thinks of the Polish prisoners in Germany and understands their boundless love of country.

Warsaw would sicken me in the long run. Thank God we’re moving on tomorrow. The ruins alone are food enough for thought but an American palace towers incongruously into the sky from among shattered walls. Half-starved children sprawl in the street and whimper for bread while provocative jazz rings out across the way, and peasants kiss the flagstones in churches while the bars seethe with unbridled, insensate revelry. The mood is universally doom-laden, but I nonetheless believe in the inexhaustible strength of the Polish people. They’re too proud for one to succeed in striking up a conversation with them. And children are playing wherever you look.

August 4, 1942: Dear Mother, Father’s imprisonment starts today, and today I received your first letter and Sophie’s. Your other letter arrived a week ago.

You can imagine that even though I wasn’t surprised by the news, I didn’t take it calmly. Indignation and turmoil-filled my heart when I read your letter, and it took me a while to calm down again. I did so mainly thanks to your generosity of spirit and all-pervading love. However, I still can’t bring myself to write an appeal for clemency. If I tried, I’d go off the rails….

Father is in for a very hard time at first, as I know too well: starved of contact with the outside world, cooped up alone in a cramped gray cell. He’ll survive, though. Being strong, he’ll emerge from captivity even stronger. I believe in the immeasurable strength of suffering. True suffering is like a bath from which a person emerges born anew. All greatness must be purified before it can exchange the narrow confines of the human breast for a wider world outside.

We shall never escape suffering, not till the day we die. Isn’t Christ being crucified a thousand times every hour, and aren’t beggars and cripples still being turned away from every door, today as always? To think that human beings fail to see precisely what makes them human: helplessness, misery, poverty….

September 18, 1942, Dear Parents: … I’ve developed a passion for riding, and it won’t let go of me. There’s nothing to beat galloping across the plain astride a fast horse, forging your way like an arrow through the head-high steppe grass, and riding back into the forest at sunset, weary to the point of exhaustion, with your head still glowing from the heat of the day and the blood throbbing in every fingertip. It’s the finest delusion I’ve succumbed to, because in a certain sense you have to delude yourself. The men call it “Russian fever,” but that’s a clumsy, feeble expression. It’s something like this: When you see the world in all its enchanting beauty, you’re sometimes reluctant to concede that the other side of the coin exists. This antithesis exists here, as it does everywhere, if only you open your eyes to it. But here the antithesis is accentuated by war to such an extent that a weak person sometimes can’t endure it. So you intoxicate yourself. You see only the one side in all its splendor and glory. I know I haven’t been here long, but I can see what an immense test of endurance a static war is….

A strong wind has been lashing the forest since dawn and shaking the trees, but it’s warm and snug in our dugout. A fire is burning and crackling in the stove, and the gloomy interior is thick with tobacco smoke.

I think of Father a great deal here. And, as one can only in Russia, I often run the entire gamut of my emotions within a few minutes, rising to a shrill pitch of fury and then, just as quickly, subsiding into an expectant, confident, equable frame of mind.

The fall brings so many things with it, among them a desire to burst one’s bonds and fly south with migrant birds to a warmer home. Big flocks of jackdaws are gathering in readiness to fly to where the sun stands overhead at noon, and crows accompany them part of the way.

Diary Entry, July 30, 1942: The plain began in Russia. Before that we were traveling through a gentle morainic landscape. Songs with a youthfully zestful rhythm were awakened in my soul by rolling hills like a frozen sea and, floating above them in the blue sky, cloud-ships that gleamed white in the afternoon sunlight. I was thinking of airy baroque churches and Mozart when, beyond the frontier, there began the broad, boundless plain where every line melts away, where everything solid dissolves like a drop in the ocean, where there’s no beginning or middle or end, where a man becomes homeless and his heart is filled with nothing but melancholy, and his thoughts resemble the ever-changing clouds that float past just as interminably, and his nostalgia resembles the wind that bears them along. All the handholds to which people cling so desperately, like home, native land, or profession, are wrenched off, as it were. The ground gives way beneath your feet, and you fall and go on falling, and just as you’re wondering where to, and all your faithful companions are deserting their broken master because they’ve nothing left to hope for, you unexpectedly and gently land, as though wafted there by angels, on the soil of Russia: on the plain that belongs to God alone and his clouds and winds.

God is closest when home is farthest, hence the young person’s desire to go forth, leaving everything behind, and wander aimlessly until he has snapped the last thread that held him captive — until he stands confronting God in the broad plain naked and alone. He will then rediscover his native soil with eyes transfigured.

Diary Entry: the next day, July 31, 1942: Gray clouds are hovering over the plain. The horizon looks like a silver ribbon dividing earth and sky. On earth, colors glow undiminished through the thin drizzle in every shade of brown, yellow, and green. When a shaft of light pierces the overcast in the far distance, an expanse of land gleams like a mirror, and the earth laughs like a child with a smile breaking through the tears in its eyes

How splendidly the flowers are blooming on this railroad embankment! As if all had assembled so that no color should be missing, they bloom here with gentle insistence — everywhere: alongside ruined buildings, gutted freight cars, distraught human faces. Flowers are blooming and children innocently playing among the ruins. O God of love, help me to overcome my doubts. I see the Creation, your handiwork, which is good. But I also see man’s handiwork, our handiwork, which is cruel, and called destruction and despair, and which always afflicts the innocent. Spare your children! How much longer must they suffer? Why is suffering so unfairly meted out? When will a tempest finally sweep away all these godless people who besmirch your likeness, who sacrifice the blood of countless innocents to a demon? The whole world is bright again, for as far as the eye can see, after this rain.

That fall, Hans and Alexander returned to Munich where they again took up their studies and the work of The White Rose. The beauty of their souls was snuffed out by the dictator’s guillotine.