Preston Tucker (1903 – 1956) was a car salesman and inventor. Anticipating WWII, he created a high speed armored car with a gun on a turret. The army thought that the car was too fast but loved the turret, confiscated the patents and used them during the war. Tucker was given contracts to build turrets for bombers and made his fortune.

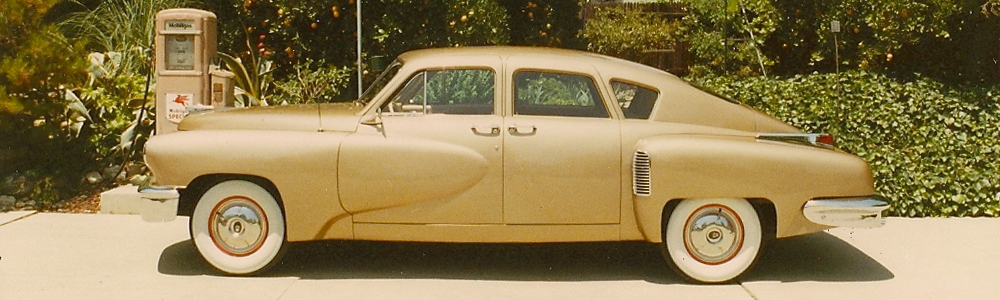

Tucker dreamed of building a passenger car with innovations such as seat belts, disk brakes, a rear engine, safety glass, pop-out windshields, a fully automatic transmission, and self-correcting headlights.

The car that Tucker designed and produced was ahead of its time in terms of safety and performance. Tom McCahill, a respected reviewer of automobiles for “Mechanix Illustrated”, wrote: “Tucker is building an automobile! And, brother, it’s a real automobile! I want to go on record right here and now as saying that it is the most amazing American car I have ever seen to date; its performance is out of this world…. The pre-select shift worked well and the car took off like a comet … [It] is one of the greater performing passenger automobiles ever built on this side of the Atlantic./This car is real dynamite! I accelerated from a dead standstill to 60 miles an hour in 10 seconds…. The car is roomy and comfortable. It steers and handles better than any other American car I have driven. As to roadability, it’s in a class by itself.” August, 1948 edition.

One of Tucker’s problems was that mass production of an automobile required tens of millions of dollars, access to a pool of skilled labor, access to raw materials, and a design and manufacturing capability that were almost impossible to assemble. Henry J. Kaiser and a consortium of his associates also tried to break into the automotive business after the Second World War. Better financed than Tucker, the Kaiser-Frazier company led other independent car makers. In 1947 Kaiser-Frazier produced 147,500 cars. By 1955, however, the company was out of business as the U.S. automotive industry consolidated into four companies, Ford, General Motors, Chrysler and American Motors. Kaiser reportedly said “We were not surprised that we had to toss $50 million into the automotive pool. We were surprised that it disappeared without a ripple.”

Tucker’s other problem was political. The big auto makers and their political friends were against him. He was subject to an extensive investigation by the Securities and Exchange Commission. Tucker and several of his associates were indicted and tried for fraud. The government’s case was so flimsy that when it concluded, the defendants rested without putting on a single witness. All of the defendants were acquitted.

Tucker’s car was never built. Detroit squelched his innovations for decades, incorporating them only under pressure from Japanese competition, the public, and the government. One wonders how many lives would have been saved had Tucker’s automobiles with seat belts been mass produced in the 1940s.

Tucker died of lung cancer in 1956, still trying to get a car company into production.

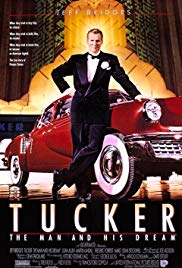

The other side of the coin is not that Tucker was corrupt or that he misled people; history has fairly well absolved him of those charges. Rather the criticism of Tucker is that he assumed everyone else wanted to take the great risks inherent in his project. For its success, Tucker’s enterprise depended on circumstances that no one could control. Moreover, he needed help from the government. The best example of this is the lease of the huge factory in Chicago. At that time the government was divesting itself of a huge number of assets accumulated to win the war. This plant was among them. Tucker was a deserving candidate to receive this building but there were other good uses for it. In addition, a supply of labor had to be found, sources of raw materials had to be secured and the design of the car had to work. These were not at all sure bets in a postwar economy suffering from labor dislocations and shortages of raw materials. The chance that something might go wrong was minimized by Tucker and by this film.

But then again, without dreams such as Tucker’s, the economy of this country would stagnate and life would be a dreadful bore. The exploration and glorification of dreams such as these are the benefit and power of this film.

There are a number of minor historical inaccuracies in the movie in addition to the error about when Tucker knew about Abe Karatz’ criminal conviction. The business about having Tucker give his own closing argument at his trial and having fifty Tucker cars line the streets near the court house is Hollywood hyperbole, but it does harken back to a real incident. Tucker was required to provide all of his records to various government agencies. His opponents had been spreading stories that he could not produce an operating car. Tucker had one load of records put into seven operating Tuckers and delivered to the offices of the investigators. The cavalcade attracted considerable public attention.