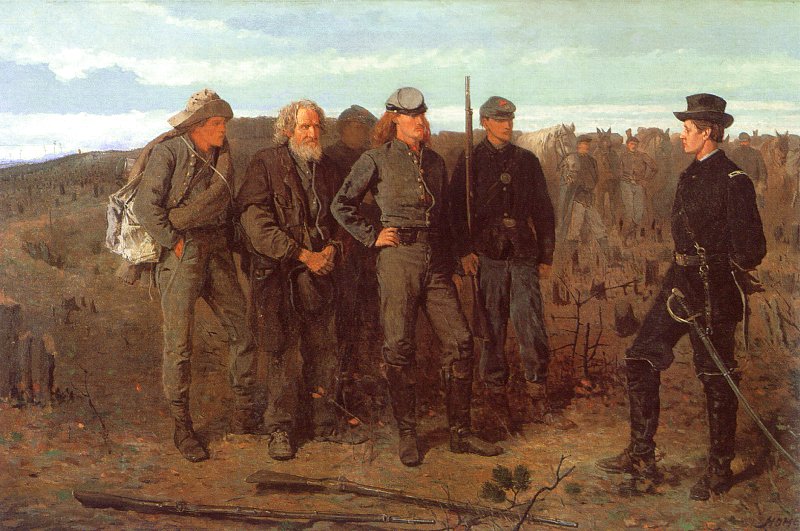

Prisoners from the Front, 1866, is Homer’s most important Civil War painting. The exhibition of this work established Homer as a major American painter. The painting depicts the capture of Confederate soldiers by Brigadier General Francis Channing Barlow (1834-1896) on June 21, 1864. The background shows the battlefield at Petersburg, Virginia. The picture captures much of the relationship between Northern and Southern soldiers during the civil war. The Northern officer is resolute, in control yet somewhat baffled by the hostility of the Southern officer facing him. He seems to want to heal the rift between them. The Union soldier guarding the prisoners is fierce and ready to pounce if they make a wrong move. He is the means by which the Union officer maintains control. The foreground and intermediate background are full of tree stumps representing the devastation of war, the young men killed, the land wasted. The three prisoners are types of Southern soldiers. The young officer is defiant, yet he knows that his life and his world have changed forever. He doesn’t like it. He has style and would be dashing except for the torn buttons of his uniform. (Compare this figure to the photograph of Confederate prisoners at Gettysburg, shown on the Learning Guide to Gettysburg.) The old man is resigned but wary. The youngest prisoner is befuddled and seems not to understand his situation. He may seem a country bumpkin but the four bullet holes in his hat are reminiscent of the foolhardy bravado of the rebel soldier in Inviting a Shot Before Petersburg.

The filmmakers studied the life of Winslow Homer and incorporated many facts about his life into the film. He visited Houghton Farm and used two children as models while he was there. During his life, especially when he became older, Homer was plagued by curious people interrupting his solitude. He fitted out his porch with uncomfortable chairs so that people who came to call would not stay long! Homer kept a slingshot with his collection of hunting rifles.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

In this film, both Fiona’s father and Homer are portrayed as suffering from PTSD. Homer’s case is mild, characterized by short flashbacks that he can manage. Fee’s father, on the other hand, is completely debilitated by the disease. PTSD is one of the few recognized psychiatric conditions whose cause is an external situation.

The National Center for PTSD, a program of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs describes Posttraumatic Stress Disorder as …

… [A] psychiatric disorder that can occur following the experience or witnessing of life-threatening events such as military combat, natural disasters, terrorist incidents, serious accidents, or violent personal assaults like rape. People who suffer from PTSD often relive the experience through nightmares and flashbacks, have difficulty sleeping, and feel detached or estranged, and these symptoms can be severe enough and last long enough to significantly impair the person’s daily life.

PTSD is marked by clear biological changes as well as psychological symptoms. PTSD is complicated by the fact that it frequently occurs in conjunction with related disorders such as depression, substance abuse, problems of memory and cognition, and other problems of physical and mental health. The disorder is also associated with impairment of the person’s ability to function in social or family life, including occupational instability, marital problems and divorces, family discord, and difficulties in parenting. …

PTSD is not a new disorder. There are written accounts of similar symptoms that go back to ancient times, and there is clear documentation in the historical medical literature starting with the Civil War, when a PTSD-like disorder was known as “Da Costa’s Syndrome.” There are particularly good descriptions of posttraumatic stress symptoms in the medical literature on combat veterans of World War II and on Holocaust survivors. …

An estimated 7.8 percent of Americans will experience PTSD at some point in their lives, with women (10.4%) twice as likely as men (5%) to develop PTSD. About 3.6 percent of U.S. adults aged 18 to 54 (5.2 million people) have PTSD during the course of a given year. This represents a small portion of those who have experienced at least one traumatic event; 60.7% of men and 51.2% of women reported at least one traumatic event. The traumatic events most often associated with PTSD for men are rape, combat exposure, childhood neglect, and childhood physical abuse. The most traumatic events for women are rape, sexual molestation, physical attack, being threatened with a weapon, and childhood physical abuse.

About 30 percent of the men and women who have spent time in war zones experience PTSD. An additional 20 to 25 percent have had partial PTSD at some point in their lives. Source: “What is Posttraumatic Stress Disorder?” National Center for PTSD, July 3, 2003;

Two Poems Referred to in the Movie

“The Artilleryman’s Vision”

by Walt Whitman

While my wife at my side lies slumbering, and the wars are over long,

And my head on the pillow rests at home, and the vacant midnight passes,

And through the stillness, through the dark, I hear, just hear, the breath of my infant,

There in the room as I wake from sleep this vision presses upon me;

The engagement opens there and then in fantasy unreal,

The skirmishers begin, they crawl cautiously ahead, I hear the irregular snap! snap!

I hear the sounds of the different missiles, the short t-h-t! t-h-t! of the rifle-balls,

I see the shells exploding leaving small white clouds, I hear the great shells shrieking as they pass,

The grape like the hum and whirr of wind through the trees, (tumultuous now the contest rages,)

All the scenes at the batteries rise in detail before me again,

The crashing and smoking, the pride of the men in their pieces,

The chief-gunner ranges and sights his piece and selects a fuse of the right time,

After firing I see him lean aside and look eagerly off to note the effect;

Elsewhere I hear the cry of a regiment charging, (the young colonel leads himself this time with brandish’d sword,)

I see the gaps cut by the enemy’s volleys, (quickly fill’d up, no delay,)

I breathe the suffocating smoke, then the flat clouds hover low concealing all;

Now a strange lull for a few seconds, not a shot fired on either side,

Then resumed the chaos louder than ever, with eager calls and orders of officers,

While from some distant part of the field the wind wafts to my ears a shout of applause, (some special success,)

And ever the sound of the cannon far or near, (rousing even in dreams a devilish exultation and all the old mad joy in the depths of my soul,)

And ever the hastening of infantry shifting positions, batteries, cavalry, moving hither and thither,

(The falling, dying, I heed not, the wounded dripping and red I heed not, some to the rear are hobbling,)

Grime, heat, rush, aide-de-camps galloping by or on a full run,

With the patter of small arms, the warning s-s-t of the rifles, (these in my vision I hear or see,)

And bombs bursting in air, and at night the vari-color’d rockets.