1. See Discussion Questions for Use With any Film that is a Work of Fiction.

[No suggested Answers.]

2. What is the difference between the meaning of the term “conscience” as understood by the real Sir Thomas More and the meaning of conscience presented in the movie?

Suggested Response:

See Helpful Background Section — Some of the Substantial Historical Inaccuracies of This Film.

3. Do most martyrs believe that their sacrifice is primarily for the purpose of establishing their independence of the forces which are opposing them?

Suggested Response:

Most martyrs relate their sacrifice to struggles beyond themselves: to a cause, to a people, or to a nation. While they certainly want to defy the forces arrayed against them, most martyrs have in mind what they consider to be the greater good. This was true of Sir Thomas More who died for the principles of Catholic Christendom.

4. Is belief in God necessary for a person to become a martyr?

Suggested Response:

No. A martyr is someone who dies for a cause, whatever it may be.

5. Remember when More asked Roper what would happen if he destroyed all the laws to get at the devil, where would he find protection if the devil turned on him? How does this argument apply to the protection of constitutional rights in the U.S.?

Suggested Response:

The Constitution of the United States has many provisions which protect individuals from the state. Examples are: (1) the right to due process which provides, for example, a jury trial for criminal cases, the right to confront your accuser, the right to a jury of your peers, the right to an attorney, etc.; (2) freedom of speech; (3) freedom of the press; (4) right to assembly and petition; (5) freedom of religion; (6) freedom to travel etc.

6. Describe how each of the following characters in this film would react to the statement that “the end justifies the means”: Cromwell, Sir Thomas More, Henry VIII, William Roper, and Richard Rich. For each provide an example of his actions in the film that leads you to this belief.

Suggested Response:

Cromwell, Henry VIII, and Richard Rich were men who believed that the end justified the means. Cromwell, as characterized in the film, would do anything to get ahead politically, such as manufacturing false charges against Sir Thomas More. Henry VIII would do anything to get a male heir, including cutting the heads off women that he had loved. Richard Rich, like Cromwell, would do anything for advancement of his career, and perjured himself at More’s trial. Thomas More would not have sacrificed principle for expediency and proved this by refusing to agree to the King’s policies on the marriage and the Church of England. William Roper was too young to be set in his ways on this. The scene in which More warns him against ignoring the legal protections of the minority to get at the devil indicates that he was leaning towards believing that the end justified the means.

7. Does the end justify the means? Is this a good standard for conduct?

Suggested Response:

No. Every ethical question must be determined on its merits but the concept that one may commit an unethical action for a good end usually leads to unethical actions. The trick in life is to find a way to achieve the ends that you want by using morally acceptable means. See Standard Ethics Questions.

8. Did Henry VIII and the political powers in England do the right thing by separating from the Catholic church in order to give Henry a wife who would provide him with a male heir? Or were they engaging in an ends justifies the means rationalization. Answer from the standpoint of a religious Catholic who lived during the reign of King Henry VIII and from the standpoint of King Henry.

Suggested Response:

The decision to allow Henry VIII to take a new wife and to separate the Church of England from Rome was a clear example of using the end to justify the means. The religious Catholic would point to the fact that King Henry had entered sacred marriage vows before God and did not have the power to break those vows. Only the Pope, as God’s representative on earth, could do that. Henry would point to the fact that his primary obligation was to the English people who needed a male heir for stability. (He was wrong, by the way. England achieved stability under his daughter, Elizabeth. But it was a reasonable assumption at the time.) Only if you discount the theory that marriage vows are sacred and can only be released by the Pope and only if you reject papal supremacy, can you find that Henry’s actions were anything other than simply an ends justifies the means argument.

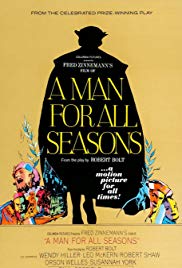

9. Why do some people call Sir Thomas More a “man for all seasons?”

Suggested Response:

There are two senses for this. First, and most commonly, that he lived his life according to strong and valid principles which did not change because of the way the wind was blowing. He did not change his opinions depending on what was popular or what the King wanted. Another way to look at the description is that More could operate effectively in many environments. He was successful as a writer, a lawyer, a judge, and Chancellor of the country. A third reason More could be described as being for all seasons is that he was a man of the Middle Ages in many things but also a leading figure of the Renaissance. See Helpful Background Section.

10. Thomas More, when he was Chancellor of England, considered all Protestants to be heretics and ordered them burned at the stake. Name one of the founding fathers of our country who also served as President who had a famous egregious blind spot.

Suggested Response:

Thomas Jefferson, the author of the Declaration of Independence, had slaves. Another possibility is George Washington, he too had slaves, although he freed them all when he died and set up a trust fund to provide for them. Jefferson didn’t have enough money to do this. The only slaves that he freed were the Hemings family.

11. Why did so many Englishmen support King Henry’s position? Did he force all of them knuckle under just because he wanted a new wife?

Suggested Response:

No. There was broad public support for Henry’s position. See Helpful Background Section.

12. What is More’s place in the history of religion in England. Was he in sync with the currents of change in the English church?

Suggested Response:

More was struggling against the flow of the currents of change in the English church. See the Helpful Background section.

13. The movie shows More as tolerant toward Protestant beliefs while he still thought them to be wrong. Is that an accurate portrayal?

Suggested Response:

No. More railed against Protestant beliefs, while recognizing that many parts and practices of the Catholic Church were corrupt and needed changing. As Chancellor More ordered Protestants burned at the stake for their beliefs in an attempt to stop the spreading heresy. He considered his persecution of heretics to be one of his greatest achievements, requesting that it be specifically mentioned in his epitaph. See Helpful Background section.

14. Why is More an interesting historical figure?

Suggested Response:

Because he straddles the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. He is clearly a man of the Middle Ages, deeply pious, burning Protestants at the stake, and dying for the pan-European community of the Catholic Church. However, he was a great humanist and a man of the Renaissance, writing one of its most influential classics, Utopia. See the Helpful Background section.

15. More claimed to be silent on the issue of the King’s divorce. Was this claim true?

Suggested Response:

No. See Helpful Background section.

16. List two ways in which the movie’s depiction of More’s trial was inaccurate.

Suggested Response:

Here are several possible facts to be included in the response: (1) The trial was conducted in private, without public spectators; (2) Cromwell was one of the judges, not the prosecutor; (3) the jury did retire but took only 15 minutes for its verdict; (4) More did not attack the marriage after he was condemned, instead he attacked the Act of Supremacy.