Preparation

A. Watch the film and decide whether to use the first 77 minutes 53 seconds only (until the view of the Earth after the pogrom), or the entire movie. If the entire movie will be shown, correct for the two egregiously incorrect scenes. See Additional Materials for Using the Whole Film.

B. Decide how to present the pre-viewing materials (steps 1 & 2 below). If student reports will be used, assign report topics in advance of the screening.

C. Decide upon post-watching activities including which Discussion Questions and/or Assignment to use.

Add-ons Linking the Lesson to Later Events in History

D. Consider adding a report on Poggio Bracciolini, book hunter extraordinaire — Teachers can introduce the class to the urgent effort in the 1300s and 1400s to find copies of the lost works of Greco-Roman literature, science, and philosophy that may have been hidden away in monastic libraries and that were quickly being destroyed by mold, book-worms and other causes. A good way to access this period is to focus on Poggio Bracciolini. A student or a group of students can research his life and present an oral report of their findings to the class. An excellent account of Sr. Bracciolini’s achievements can be found in The Swerve: How the World Became Modern by Stephen Greenblatt. This is an excellent work on a pivot point in history. It provides a lengthy description of Sr. Bracciolini and his contribution to the effort to rescue ancient classics from oblivion. The assignment should be given enough in advance to allow students to complete their work and give their report on the day the film is finished. In the alternative, teachers can provide this information through direct instruction.

E. Consider a section on “From Aristotle to Ptolemy to Columbus” — An excellent way to show students the reach of Aristotle’s love for learning and Ptolemy I Soter’s vision for a library and community of scholars is to read to the class or describe the Preface and the Epilogue to the book, The Rise and Fall of Alexandria by Justin Pollard and Howard Reid. The Preface describes how in 1295 CE Maximos Planudes, an Eastern Orthodox monk, found a treasure hidden in a used book-seller’s shop. It was a copy of Geographia, Claudius Ptolemy’s book setting out the parameters of the discipline of geography. Written in Alexandria in the second century CE and originally deposited in the Great Library/Museum, it had not been seen for a almost a thousand years and was thought to have been lost when the Library/Museum was destroyed. In this book Ptolemy contends that the world is, in fact, a sphere. In their Epilogue, Pollard and Reid describe how, some 1200 years after it was written, Ptolemy’s masterpiece made its way to the hands of a young explorer — Christopher Columbus.

In presenting this information to students, remind them that in the fifteenth century Ptolemy’s model of the geocentric universe still held sway — in other words, when Columbus read what Ptolemy had written, the words had the authority of the man who had figured out how the heavens worked . . . or so everyone thought at the time.

Thus, Aristotle’s belief in the power of knowledge — transmitted in Macedonia to a young boy who later became Ptolemy I Soter, the ruler of Egypt, leading to the creation of the knowledge industry of Alexandria creating the conditions for Claudius Ptolemy to do his pioneering work in astronomy and geography — helped to inspire Christopher Columbus to undertake the voyage that led to the discovery of a new world.

Presenting this information involves purchasing the book or getting a copy from a colleague or a library. It’s well worth the effort or the expense.

Step by Step

1. Student Handout/Lecture: The following introduction can be given by the teacher or printed and given to the class to read. Click here for a version of the Introduction in word processing format suitable to be printed and distributed to students. Teachers giving the introduction themselves, can print and highlight the introduction to serve as notes for the lecture.

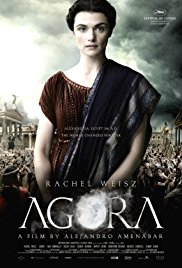

Introduction to Agora

The city of Alexandria in Egypt was the third great city of the Greco-Roman world, often surpassing Athens and Rome in scholarship, learning, and artistic achievement. It had a renowned market and the most complete library the world had ever seen. For six centuries from its founding in the 3rd century BCE to the assassination of Hypatia in 415 CE, Alexandria was a Greek city with a Greek tradition of scholarship and philosophical inquiry in which a form of Greek was the language of choice. The Greek influence in the city remained strong for centuries after that, until the Arab conquest of the city in the 642 CE.

A few of the great philosophers, scientists, and mathematicians of ancient Alexandria and their achievements are briefly described below.

Euclid set out the parameters of geometry for the next 20 centuries. Euclid’s geometry is still used today, and his book on geometry is still published.

Claudius Ptolemy whose works on geography and astronomy were only superseded in the Renaissance, some 12 centuries after his death, lived and worked in Alexandria. While Ptolemy’s astronomy has been discredited, many aspects of his Geographia, including the concept of a spherical earth measured by latitude and longitude, are still in use today.

Archimedes, perhaps the greatest ancient mathematician, did most of his work in Syracuse, but he studied and got his start in Alexandria.

Galen, the great physician and physiologist, learned his trade and worked in Alexandria before being brought to Rome. While in Alexandria, Galen learned about or discovered the circulation of the blood, a finding forgotten in Europe and not rediscovered until 1628.

Appollonius wrote Jason and the Argonauts.

Clement of Alexandria was a great Christian theologian.

Philo was a Jewish scholar and theologian.

Hero, also Heron, was a lecturer at the Great Library/Museum in mathematics, mechanics, physics, and pneumatics. He was also one of the ancient world’s greatest inventors, creating, for example, automatons which worked on gravity and hydraulics, an automatic vending machine for holy water, and a wind-powered organ. He also wrote a description of a steam engine. Hero’s greatest work of mathematics was lost until it was found in 1896, translated into Arabic.

Hypatia was the greatest female mathematician, astronomer, philosopher, and educator of the Greco-Roman civilization. None of Hypatia’s work has survived, but the following description is echoed by several ancient sources:

Revered Hypatia, ornament of learning, stainless star of wise teaching, when I see thee and thy discourse I worship thee, looking on the starry house of the Virgin [Virgo]; for thy business is in heaven. [Palladas, Greek Anthology (XI.400)]

Hypatia was respected by the elites of Alexandria and had extensive moral authority in the city. She supported Orestes, the Roman Prefect, in his political struggle with Cyril, the Patriarch of Alexandria. She was brutally murdered in 415 CE by Cyril’s supporters with his encouragement, direct or indirect.

There were in ancient Alexandria many other scholars, not all of them were as famous or accomplished as these superstars, but they were philosophers, scientists, and teachers in the Hellenistic tradition. They made valuable contributions to the advancement of knowledge and educated the elites of their times. (The word “Hellenistic” comes from “Hellas” the Greek word for the country of Greece.)

And all of this was by design! Ptolemy I Soter (ruled from 323–283 BCE) was the second Hellenistic ruler of Egypt; Alexander the Great having been the first. (Alexander got his start as the ruler of Macedonia, a Greek kingdom.) Ptolemy I Soter was the son of a Macedonian aristocrat and one of the small group of boys at the Macedonian court who were schooled along with Alexander by Aristotle. Later, Ptolemy became one of Alexander’s most trusted generals.

Alexander the Great called Aristotle his second father. Alexander, Ptolemy, and most of the Western world, at least until the time of the Renaissance, revered Aristotle and considered him to be the most authoritative scientist and philosopher who had ever lived.

When Alexander died, his generals divided up the Macedonian Empire. Ptolemy I seized Egypt, which due to the annual floods of the Nile river, was one of the richest provinces of the Empire. Following the precepts of Aristotle, Ptolemy I wanted his newly acquired domain to benefit from the best knowledge available in the world. He took the first steps to establish the Library/Museum of Alexandria and its surrounding community of scholars. The Library was completed under his son, Ptolemy II.

Scribes from the Library/Museum borrowed scrolls and books from all over the ancient world and copied them. Founded in the third century BCE the Library/Museum grew to 500,000 volumes and the overflow was housed in a “Daughter Library” located in a pagan temple complex called the Serapeum. The great Library/Museum was burned and rebuilt at least once. Julius Caesar was responsible for the first destruction of the library in 48 BCE when, as a military maneuver, he set fire to ships in the harbor, and the flames accidently spread to buildings in the city. There is evidence that the library was rebuilt after that, but historians have not been able to determine how or exactly when the Great Library or the “Daughter Library” were finally destroyed. However, they do know that Theon, Hypatia’s father, was the last Trustee of the Library, or whatever was left in the late fourth century CE.

In the 4th and 5th centuries CE, Christianity was a relatively new religion that had only recently gained acceptance in the Roman Empire. For hundreds of years before this time Christians had been killed and persecuted by Pagans who often acted with the authority of the Roman state. While the Roman Emperors were Christian during the times shown in this film, Paganism was not just a harmless discredited mythology, as it is today. It was a genuine threat to Christians, and Pagans did not hesitate to kill Christians. The history of 4th and 5th century Alexandria shows an early Christianity with strong memories of past persecution, feeling the need to rid society of any influence that could challenge the new faith.

The temple complex called the Serapeum was destroyed in 391 CE on the instructions of the bishop of Alexandria. While historians do not know if any scrolls or books of the “Daughter Library” survived to that time, had they existed they would probably have been destroyed along with the buildings and cult objects of the temple. The community of scholars continued without the Library/Museum but was then dealt a significant blow with the assassination of Hypatia in 415 CE. The death of Hypatia was a milestone in the slow de-Hellenization of the city. While Alexandrians continued to make significant contributions to the Neoplatonic philosophy that Hypatia had taught, no mathematician approaching Hypatia’s status ever worked in Alexandria again. The city was changing.

In the streets violent religious extremism and an associated rise in ethnic tensions were fanning the flames of [Egyptian] nationalism. Customs were changing, shunning the “foreign” Greek influence of Hypatia’s Hellenism, despite the fact that it had been the cornerstone, indeed the very raison d’etre, of the city. [The Rise and Fall of Alexandria, Pollard and Reid, p. 280]

It is estimated that only about 1% of the half-million books and scrolls in the Great Library/Museum of Alexandria survived into the Renaissance and from there into modern times.

About the Movie

One of the themes in this film is a criticism of intolerance and the tit-for-tat retaliation often involved in ethnic and religious strife. The movie shows intolerance of Christians by Pagans and intolerance of Pagans by Christians. Alexandria had a very large Jewish community. The film shows Christians persecuting Jews, Jews retaliating, and Christians taking retribution for that retaliation.

Agora is historical fiction: entertainment set in the past with some reference to people and places that actually occurred. But since the filmmakers were not present back in Alexandria in the 4th and 5th centuries and because the historical records are very sparse, much of what is shown on the screen came from educated guesses schooled by the filmmakers’ study of the history of the times. In addition, in all historical fiction there is a tension between accurately describing what occurred and telling a good story. This often leads to telescoping events in terms of time, to moving events around on the time-line, and the creation of scenes which are different from but which are intended to represent what actually occurred.

All of the major characters in this movie, except for the slaves, are depictions of people who lived in ancient Alexandria in the 4th and 5th centuries. All of the slaves are fictional. While a man named Orestes was for a short time the Roman Prefect of Egypt and was advised by Hypatia shortly before her death, he was never her student. The young Orestes shown as Hypatia’s student is a fictional character, although the incident in which Hypatia discouraged a student who fell in love with her as shown in the movie is described in the historical literature.

The movie shows the destruction by a Christian mob of the Serapeum in 391 BCE, and the moviemakers assumed that the “Daughter Library” had continued to exist and was destroyed along with the temple complex. However, no one knows for sure whether the “Daughter Library” still existed in the Serapeum at the time the temple was destroyed. Historians take different positions on this question. This scene should be seen as a symbol for the general decline in learning as the ancient Greco-Roman civilization crumbled and Medieval times, also called the Dark Ages, began.

This version of the film is in English, but of course, the characters weren’t speaking English — but they weren’t speaking Egyptian either, or even Latin. As you watch the movie remember that Hypatia, Orestes, Cyril and all the rest were speaking Greek.

[End of Written/Lecture Introduction]

2. Student Reports: After the introduction described in step #1 and before showing the film, have students present short reports on the following topics. This information will help the class get the most out of the movie. The minimal information to be conveyed to students is set out in brackets below the topic. If the report does not include this information, the teacher should supply it to the class along with any other insights that the teacher believes will be helpful in understanding the film. Delete any topics already covered by the class. In the alternative, teachers can provide this background in a lecture using the material in brackets as lecture notes.

The Spread of Greco-Roman civilization

[Beginning in the seventh century BCE Greek civilization was spread around the Mediterranean and Black seas by traders and then by colonization. There were hundreds of Greek colonies. Greek civilization was later spread by the military conquests of Alexander the Great 336 – 323 BCE and then by the Roman Empire which had adopted many aspects of Greek culture. Often, as in Egypt, the Greek civilization combined with the local cultures but sometimes the Greeks in foreign lands kept apart from the indigenous people.]

Ptolemy I Soter, including his theft of the body of Alexander the Great

[If the introduction to the movie is not given (see Step 1 above) then this presentation should include the information about Ptolemy I Soter contained in the introduction]. Ptolemy hijacked the mummified body of Alexander the Great and its beautifully made golden sarcophagus as they were being sent to Macedonia to be interred in the plot set aside for Macedonian kings. Ptolemy took the remains to Egypt, where the people believed that Alexander was the son of Egyptian gods. Ptolemy’s possession of the body of Alexander gave him credibility in the eyes of the Egyptians. Another way in which Ptolemy gained favor with the Egyptians was to venerate the Apis bull, who the Egyptians believed was sacred to one of their gods. Ptolemy I Soter was a strong king and ruled Egypt for 40 years, from 323–283. He established a dynasty of pharaohs in Egypt which lasted until 30 CE, almost three centuries. Cleopatra VII Philopator, a direct descendant of Ptolemy and the first Ptolemaic ruler to speak Egyptian (all the others spoke only Greek), committed suicide in 30 BCE shortly after the suicide of her consort, the Roman general Mark Antony.]

Creation of the City of Alexandria

[In the third century BCE, Alexander the Great invaded Egypt, at that time ruled by the Persian Empire. The country capitulated, virtually without a fight, and Alexander spent six months in Egypt setting up his government and learning about Egyptian culture and religion. He was pronounced son of the gods by the priests of the oracle at Silwa. Alexander wanted to shift the focus of Egypt from the Nile to the Mediterranean and chose the location of a new city to be named Alexandria. The city had a good harbor and was to be a trading center and the capital of a Hellenized Egypt. Alexander mapped out its main streets and buildings. He then left Egypt and died soon after. After Ptolemy I Soter gained control of Egypt he determined to complete the design of Alexandria, to construct the city, and to make it his capital as well as the intellectual center of the ancient world. He and the Ptolemaic Pharaohs who followed him succeeded admirably, establishing the great Library/Museum of Alexandria and the community of scholars of which Hypatia was a member.]

The Library/Museum at Alexandria

[The Library/Museum was the center of learning for a large group of scholars and also a pagan religious center. The Library/Museum attracted scholars and functioned as a center of learning for all areas of knowledge; it could be said that the ancient City of Alexandria was the first university of Western civilization.]

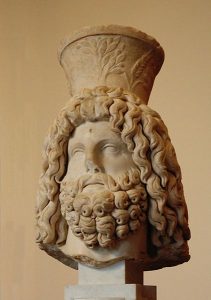

Serapis and the Serapeum at Alexandria

[When Ptolemy I Soter sought to rule Egypt, he knew that it was important to respect the Egyptian gods, but he also needed to retain the loyalty of his Greek troops. One of the ways that he did this was to take what had been a minor god, Serapis, give him attributes of both Egyptian and Greek gods, and elevate him to the status of the chief god of the city. A commission was given to a master Greek Sculptor to create an imposing statue of the new improved god. It was housed in the Serapeum, a large temple complex that later included the “Daughter Library” in which books and scrolls that would not fit into the Great Library/Museum were stored. The Serapeum was destroyed in 391 CE, but it is not known whether the Daughter Library had survived to that point. The circumstances of the destruction of the Serapeum are that after a group of Pagans attacked Christians, the Christians responded and threatened to overwhelm the Pagans. The Pagans took refuge in the Serapeum which was then besieged by the Christians. A standoff ensued. The parties submitted the dispute to the Emperor, himself a Christian, who ordered that the lives of the Pagans would be spared but the Christians could do what they wanted with the Serapeum The Christian Bishop of Alexandria, Theophilus, ordered that that the Serapeum be destroyed. Any remaining scrolls and books in the Daughter Library would have been destroyed at that point.]