The information will increase students’ appreciation of the movie.

The Second World War was a “total war” in which the entire economy and all scientific and industrial capacities of the combatants were harnessed to the war effort. Thus, factories and means of transportation were considered legitimate targets. Many of these targets were in civilian areas.

In addition, attacks on civilians were used to terrorize the opponents and break their will to resist. In both cases, the war of terror on civilians was begun by the Axis countries. The Germans bombed London and other cities in Britain early in the war. The goal was to destroy the morale of the British people and soften up the country for a German invasion. The Germans also killed millions of people in the areas that they controlled. Eleven million people died in German concentration camps, six million Jews and another five million non-Jews, such as Poles, political opponents, the Roma, the handicapped and the mentally ill. An estimated 20 million citizens of the Soviet Union were killed by the Germans.

The Japanese army also killed millions of civilians:

From the invasion of China in 1937 to the end of World War II, the Japanese military regime murdered near 3,000,000 to over 10,000,000 people, most probably almost 6,000,000 Chinese, Indonesians, Koreans, Filipinos, and Indochinese, among others, including Western prisoners of war. This democide was due to a morally bankrupt political and military strategy, military expediency and custom, and national culture (such as the view that those enemy soldiers who surrender while still able to resist were criminals). STATISTICS OF DEMOCIDE, Chapter 3. Statistics Of Japanese Democide, Estimates, Calculations, And Sources by R.J. Rummel, University of Hawaii, accessed on November 23, 2011.

Conditions for Allied prisoners of war in Japanese prison camps were extremely brutal.

The Allies (the U.S., Britain, and the U.S.S.R.) had been appalled by the German and Japanese attacks on civilians. As the war progressed, the people of the Allies and their governments became furious and willing to kill massive numbers of civilians to attain victory. Think of what the reaction was for 9/11, in which about 3000 people were killed. What if there had been one-hundred 9/11s or one thousand?

The Allies repaid the Germans and the Japanese for their atrocities against civilians, primarily by devastating German and Japanese cities from the air and killing even more civilians. By early 1945, the U.S. had almost complete control of the skies over Japan as well as bases close to the Japanese home islands. In Japanese cities, most buildings were built of wood and paper. Realizing this, the Army Air Forces favored incendiaries that burned vast areas. Before the end of the war, 66 major urban centers in Japan were severely damaged by air strikes, in addition to the two cities that suffered atomic bomb attacks.

It is true that the U.S. dropped leaflets before the raids warning civilians to evacuate the cities that were attacked from the air. However, as a tactic of psychological warfare, the U.S. dropped similar leaflets on cities that were not going to be attacked, disrupting economic activity and causing confusion and panic. As a result, many Japanese ignored the warnings and died when the attacks came.

The incendiary attack on Tokyo, the most destructive air raid in history, occurred on March 9 & 10, 1945. One thousand U.S. bombers dropping incendiary bombs created a firestorm that devastated 15 square miles of the city and killed approximately 100,000 people, with hundreds of thousands injured. “In the aggregate, some 40 percent of the built-up area of the 66 cities attacked was destroyed. Approximately 30 percent of the entire urban population of Japan lost their homes and many of their possessions.” United States Strategic Bombing Survey Summary Report (Pacific War) July 1946, p. 17 Total civilian casualties in Japan, as a result of nine months of air attack, including those from the atomic bombs, were approximately 806,000. Of these, approximately 330,000 were fatalities. These casualties probably exceeded Japan’s combat casualties, which the Japanese estimate as having totaled approximately 780,000 during the entire war.” Ibid. p. 20. Some of these casualties were children or were the parents of children, leaving their children orphaned.

The growing food shortage was the principal factor affecting the health and vigor of the Japanese people. Prior to Pearl Harbor the average per capita caloric intake of the Japanese people was about 2,000 calories as against 3,400 in the United States. The acreage of arable land in Japan is only 3 percent of that of the United States to support a population over half as large. In order to provide the prewar diet, this arable acreage was more intensively cultivated, using more manpower and larger quantities of fertilizer than in any other country in the world; fishing was developed into a major industry; and rice, soybeans and other foodstuffs amounting to 19 percent of the caloric intake were imported. Despite the rationing of food beginning in April 1941 the food situation became critical. As the war progressed, imports became more and more difficult, the waters available to the fishing fleet and the ships and fuel oil for its use became increasingly restricted. Domestic food production itself was affected by the drafting of the younger males and by an increasing shortage of fertilizers.

By 1944, the average per capita caloric intake had declined to approximately 1,900 calories. By the summer of 1945 it was about 1,680 calories per capita. Coal miners and heavy industrial workers received higher-than-average rations, the remaining populace, less. The average diet suffered even more drastically from reductions in fats, vitamins and minerals required for balance and adversely affected rates of recovery and mortality from disease and bomb injuries.

Undernourishment produced a major increase in the incidence of beriberi and tuberculosis. It also had an important effect on the efficiency and morale of the people, and contributed to absenteeism among workers.” Id. pp. 20 & 21.

Before the atomic bombs were detonated: Yokohama, about the size of Cleveland was 58% destroyed; Tokyo, about the size of New York, was 51% destroyed; Nagoya, about the size of Los Angeles, was 40% destroyed; Osaka, about the size of Chicago, was 35% destroyed; Siumonoseki, about the size of San Diego, was 37.6% destroyed; Kure, about the size of Toledo, was 42% destroyed; Kobe, about the size of Baltimore, was 56% destroyed; Omuta, about the size of Miami, was 36% destroyed; and Wakayama, about the size of Salt Lake City, was 50% destroyed. Many other Japanese cities also suffered massive damage. For these numbers and more comparisons, see 67 Japanese Cities Firebombed in World War II and Strategic bombing during World War II from Wikipedia.

Note to Teachers:

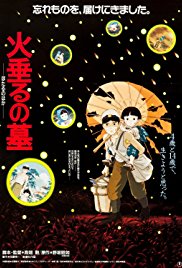

Before showing the film, tell students that the movie is based on a book written by a man who, with his sister, tried to survive after the Americans bombed their city.

FOLLOW UP EXERCISES

Section One: The Difficulty of Thinking About Mass Casualties

- Before class, write on one section of the board the following quote: Adolf Eichmann: “One hundred dead are a catastrophe, a million dead are a statistic.” At the beginning of the class, ask if anyone knows who this man is and what he did. [Adolf Eichmann was the man in charge of Hitler’s “Final Solution.” After WWII, he escaped to Argentina and hid there for many years. In 1960, his location was discovered by the Israeli secret service. They kidnapped Eichmann and took him to Israel. He was put on trial, convicted of genocide, and executed.]

- On another section of the board write the numbers 806,000 and 330,000 across the top of the blackboard space in your classroom. Based on your introduction to the movie, the class should know what the numbers mean.

- Ask the class if anyone has an idea about how to help people think about the deaths of 330,000 people so that it’s more than just a statistic. You probably won’t get any takers, but if anyone comes up with a good idea, have the class go through the exercise. [And please send it to us so that we can publicize it.]

Section Two: The Consciousness of Each Person is an Entire World

- Tell the class that it has been said that “each person’s consciousness is an entire world.” For emphasis, you might want to write the phrase on the board in a different color and in larger letters than the quote from Eichmann. This phrase should remain on the board through the rest of the lesson.

- Instruct the class to take a piece of lined paper and to write their name, the period, and the date at the top. Then instruct them to write the phrase, “Each person’s consciousness is an entire world” just below their identifying information. Finally, ask the students to think of a person living in their family or their community. It can be a child or an adult. It can be themselves or another person. Give the class fifteen minutes to list of the most important things about the world of this person’s consciousness. They should include information on the person’s life: what are his or her interests, family and friends, favorite things to do, prized possessions, pets, and what they love about their home; what he or she is good at and what motivates him or her. Tell students that they can also describe their fondest memories, detailing their dreams for the future, and explain what makes them unique or different. Tell the class that the lists will be graded on imagination, effort, grammar, punctuation, and penmanship.

- When time is up, ask for volunteers to read their lists to the class and select three. Collect the other lists and time the presentations of the volunteers. Compliment the volunteers on their work.

- Say something to the effect of “That’s three people, and we’ve just begun to explore their worlds.” Tell the class that it took about 30 seconds (or however long it took) to read just a short description of a small part of the life of a person. And there was much more to each of these lives than what was just described. The comment that the 330,000 Japanese people killed in the air raids had their own worlds just like the people the class has written about and “just like all of us in this room.” [All quotations in this exercise are only suggestions as to phrasing. Put them into your own words and tailor them to the class.]

Then remind the class that most of the people who were injured or died suffered burns. Burn injuries are very painful and burning to death is one of the most painful ways to die.

Section Three: The Survivors

- Ask the class to describe the lives of the survivors. Look for the following: memories of their friends or loved ones who died or were injured; survivor guilt; their own injuries, like disfiguring burns, or loss of function of their arms, legs or hands; living in housing that had been damaged, being orphaned and living without parents, etc. Some, like Seita and Setsuko, will not themselves die immediately but will suffer for a while and then become fatalities. Their injuries may kill them slowly or they may starve to death.

Section Four: Remembering the Dead

- Tell the class, “Every human being has the right to have their life remembered: by people they loved, people they helped, co-workers or fellow students, and friends.” Remind them that earlier in the day it took only 30 seconds (or however long it was) to read just a small part of the lives of other human beings, and we had just scratched the surface of the world that was their consciousness. If we took just 30 seconds to read a list of the important parts of the worlds of the first 330,000 people who died from the bombing campaign, it would take us 165,000 minutes, which comes to about 115 days reading 24 hours a day. (If the figure you use is different than 30 seconds, the numbers will be different. You may want to do the math for or with the class.) (The same exercise can be done with the eleven million people, six million Jews and five million others, who died at the hands of the Germans in the Holocaust.) Ask whether they now understand the full meaning of the deaths of 330,000 people. The correct answer is probably “no, we’re just beginning to understand the horror of it all.”