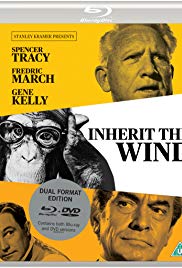

INHERIT THE WIND

SUBJECTS — U.S./1913 – 1929 & Tennessee; Cinema;

SOCIAL-EMOTIONAL LEARNING — None;

MORAL-ETHICAL EMPHASIS — Trustworthiness.

AGE: 12+; No MPAA Rating;

Drama; 1960; 128 minutes; B&W. Available from Amazon.com.

There is NO AI content on this website. All content on TeachWithMovies.org has been written by human beings.

SUBJECTS — U.S./1913 – 1929 & Tennessee; Cinema;

SOCIAL-EMOTIONAL LEARNING — None;

MORAL-ETHICAL EMPHASIS — Trustworthiness.

AGE: 12+; No MPAA Rating;

Drama; 1960; 128 minutes; B&W. Available from Amazon.com.

TWM offers the following worksheets to keep students’ minds on the movie and direct them to the lessons that can be learned from the film.

Film Study Worksheet for a Work of Historical Fiction and

Worksheet for Cinematic and Theatrical Elements and Their Effects.

Teachers can modify the movie worksheets to fit the needs of each class. See also TWM’s Historical Fiction in Film Cross-Curricular Homework Project.

This drama is loosely based on the “Scopes Monkey Trial,” Dayton, Tennessee, 1925. However, the inspiring event for “Inherit the Wind” was the red scare of the late 1940s and early 1950s and the excesses of redbaiters such as Senator Joseph McCarthy and the House UnAmerican Activities Committee. Therefore the “trial” in the film departs to some extent from the historical record. The movie is based on a play by Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee which opened in 1955. The play and the films based on the play have come to symbolize the Scopes trial in the national consciousness of the United States.

Selected Awards: 1960 Berlin International Film Festival: Best Actor (March); 1960 National Board of Review Awards: Ten Best Films of the Year; 1960 Academy Award Nominations: Best Actor (Tracy), Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Black and White Cinematography, Best Film Editing.

Featured Actors: Spencer Tracy, Fredric March, Florence Eldridge, Gene Kelly, Dick York.

Director: Stanley Kramer.

The Scopes trial and the personalities involved exemplify important conflicts in American thought including:

The right of the majority in any state to control what children are taught in the schools vs. academic freedom for teachers;

Fundamentalist religion which views the Bible as a source of knowledge about nature vs. religious beliefs which find no conflict between scientific discoveries and belief in God and the Bible;

Reliance on tradition vs. willingness to accept the newest revelations of science;

The interest of a majority in any state in preventing the public schools from being used to teach scientific theories that contradict its religious beliefs vs. separation of church and state;

Belief that knowledge springs from the people vs. reliance on experts;

Creationism vs. the theory of evolution;

Regionalism vs. nationalism.

The Helpful Background Section describes each position in the words of the participants in the Scopes trial. Discussion questions relating to each position are also provided.

MINOR. “Inherit the Wind” is not, and was not intended to be, historically accurate. In addition, creationists may object to this film.

Parents who believe in creationism will probably not want to show this film to their children. Its premise is that Darwin’s theory of evolution applies to the development of mankind and that it is not inconsistent with anything in the Bible. For everyone else, this film is a treasure trove. Not only is the movie a classic representation of a classic play, it raises all of the issues described in the Benefits section.

Ask and help your children to answer the Quick Discussion Question. Another interesting way to discuss this film is to talk about the two great protagonists: William Jennings Bryan and Clarence Darrow. They are fascinating people and understanding their careers will illustrate important facts about the history of the period.

See the Learning Guides to The Crucible and High Noon for background concerning the Red Scare of the late 1940s and early 1950s. The anti-evolution campaign of the 1920s was not as destructive to society as the Red Scares but there were striking parallels between the two situations. People were singled out for certain beliefs, i.e., belief in evolution in the anti-evolution campaign and left-wing political views in the Red Scare. Some people, almost entirely teachers and college professors in the anti-evolution campaign, lost their jobs.

In the 1920s, religious fundamentalists objected to the teaching of Darwin’s theory of evolution in public schools. They contended that evolution was inconsistent with the biblical account of creation. William Jennings Bryan, the great Populist politician, was a leader of this movement. Strong opposition to the anti-evolution movement came from “modernist” religious leaders who saw no conflict between evolution and religion. Scientists who were convinced of the truth of the theory of evolution and who saw it as fundamental to the science of biology viewed the anti-evolution crusade as an attack upon science. Civil libertarians viewed the effort to prohibit the teaching of evolution in the schools as undermining the separation of church and state, academic freedom, and freedom of religion.

In 1925, the state of Tennessee passed a law making it a crime “to teach any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals.” Twenty other states had either passed or were considering such laws at the time. Seeing a danger to academic freedom and the constitutionally mandated separation of church and state, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) wanted to attack the law on constitutional grounds. It advertised for a teacher willing to challenge the law and offered to pay the costs of the defense.

The ACLU advertisement was seen by George W. Rappelyea, a mining engineer who lived in Dayton, Tennessee. Rappelyea, a native New Yorker, had been outraged when he witnessed a local preacher at the funeral of an eight-year-old boy tell the congregation, including the weeping parents, that “This here boy ’cause his pappy and mammy didn’t get him baptized, is now awrithin’ in the flames of hell.” Rappelyea protested these statements but was told that outsiders shouldn’t interfere with local religious beliefs. (This event is echoed in a scene in the movie.)

When the law prohibiting teaching evolution in public schools was passed, Rappelyea saw the same attitude behind the new statute that he had seen in the preacher. Rappelyea suggested to John T. Scopes, a young high school teacher, that he challenge the law. (Clarence Darrow for the Defense, pages 343 & 345) Scopes was a math teacher and football coach, who had never actually taught evolution but had only filled in for the biology teacher for two weeks. However, Scopes, like most educators then and today, could not see how biology could be properly taught without the concept of evolution. He agreed that the law should be challenged. Rappelyea discussed the proposal with several leading citizens of Dayton who were interested in the business opportunities that a notorious trial would bring to Dayton. They wanted to use the trial to “put Dayton on the map.” Among the Dayton participants, including the prosecutors, the trial was always a friendly affair. For example, because of the extremely hot weather during the trial, Scopes and some of the prosecutors went swimming together at the lunch breaks. Despite his eventual conviction, Scopes was offered a teaching contract for the next year by the same man who had been the official complainant in the case against him. The good feeling even extended to the outsiders. While the public relations battle between Clarence Darrow and William Jennings Bryan was deadly serious, the townspeople made the defense attorneys feel at home and ensured that they were comfortable. At the conclusion of the trial, Bryan offered to pay Scopes’ fine.

William Jennings Bryan, three-time Democratic Party candidate for President of the United States, former Secretary of State, fundamentalist religious writer and frequent Chautauqua speaker against “Darwinism,” was asked by a fundamentalist Christian group to aid the prosecution. When Bryan accepted the invitation, Clarence Darrow, renowned attorney, civil libertarian and agnostic, volunteered to help the defense. Bryan and Darrow had worked together on reformist and liberal causes in the past. While the ACLU had not wanted Darrow to be on the defense team because it was afraid that his presence would change the nature of the debate from one over individual freedom to an attack on fundamentalist religion, Scopes accepted Darrow as his attorney and the ACLU had no choice. (See below for a more complete description of the many accomplishments of William Jennings Bryan and Clarence Darrow.)

Bryan and Darrow were not the only lawyers involved in the trial. The defense team consisted of a local counsel and several attorneys sent from New York by the ACLU. The prosecution was led by a local prosecutor, assisted by several other attorneys and by Bryan. While Bryan was the best-known attorney for the prosecution, he hadn’t practiced law in decades.

The goal of the defense, throughout the trial, was not to get an acquittal. Rather, the defense attorneys, with Scopes’ blessing, wanted to build a court record from which they could bring an appeal on constitutional grounds of separation of church and state and freedom of speech. In addition, the defense wanted to publicize evolution and show the logical inconsistency of those who claimed that it was contrary to biblical teachings. As Darrow put it, he wanted to free public education from the control of “bigots and ignoramuses.” He also thought that Bryan had become dangerous and he wanted to put Bryan “in his place.”

Bryan’s goals were to vindicate the right of the majority to control what was taught in the public schools, to protect children from what he considered to be dangerous doctrines, and to promote fundamentalist religion.

The defense tried to call experts to show that the theory of evolution was scientifically legitimate and that it was compatible with the biblical story of creation. The trial judge excluded all of the expert evidence

To get around this ruling, Darrow called Bryan to the stand as an expert on the Bible, a subject that Bryan had written and lectured about extensively. Attorneys representing one side or the other almost never testify at a trial, but, in this case both Bryan and Darrow knew that the real trial was in the court of public opinion. While the judge would have denied the request for Bryan to testify if he had objected, Bryan accepted Darrow’s challenge.

Darrow made Bryan look like a fool. Darrow’s strategy was to let Bryan talk himself out on a limb and then to either saw it off, or simply let it break from the weight of what Darrow considered to be the bad logic of Bryan’s position. Darrow started his examination of Bryan by establishing Bryan’s expertise in the Bible. Darrow then asked Bryan if he believed the biblical story that Jonah had actually lived three days inside of a whale. Bryan’s response was that he did and that “One miracle is just as easy to believe as another.” (See Learning Guide to “Moby Dick” for a brief discussion of the story of Jonah and the whale.) Then Darrow asked Bryan about the biblical account of how Joshua made the sun stand still for the purpose of lengthening the day, obtaining an admission from Bryan that since the earth goes around the sun, the Bible must have meant that the earth stood still, because the Almighty “might have used language that could be understood at the time.” Darrow then asked “Have you pondered what would actually happen to the earth if it stood still suddenly?” Bryan responded: “No. The God I believe in could have taken care of that….” When Darrow turned to the story of the flood, Bryan stated that he, along with most Fundamentalists of that time, accepted Bishop Usher’s calculation, made in the Seventeenth Century, that the flood had occurred in 2348 B.C.E. Bryan denied any knowledge of civilizations traced back more than 5,000 years, such as the Egyptian civilization or that of the Chinese. He stated that, on these and many other subjects of human and natural history, the Bible gave him “all the information I want to live by, and to die by.” Darrow then turned to the Tower of Babel. Bryan stated that approximately 4200 years ago, every human being spoke the same language. He also said that all the languages and dialects of the world had originated since that time. Bryan and Darrow at Dayton page 148. On the subject of creation, Bryan volunteered that the first day could have been 25 hours long or a period of time, perhaps millions of years. This admission brought gasps from the audience of fundamentalists and it, as well as Bryan’s admission that it was the earth and not the sun that had stood still on Joshua’s command, alienated his audience. [Scopes, Center of the Storm, p. 178 – 181.]

In sum, during the cross-examination, Darrow got Bryan to admit that he didn’t read the Bible literally in all respects but that he selected certain parts to believe literally. Thus Bryan’s anti-evolution beliefs were not compelled by the Bible, but only by his personal choice to take certain parts of the Bible literally. Bryan’s testimony was struck from the Court record as irrelevant but it left a lasting impression in the court of public opinion. (Bryan and Darrow at Dayton, pp. 133 et seq.) Bryan had intended to call the defense attorneys to the stand so that he could cross-examine them, but after Darrow’s examination of Bryan, the chief prosecutor refused to permit this. (An excellent eye witness account of this examination by Scopes himself can be found in Center of the Storm pages 165 – 189.)

The defense, deprived of its ability to put on evidence, had provided affidavits from its experts to establish a record for the appeal. After the examination of Bryan by Darrow, the defense stipulated to a finding of guilty, not wanting to risk an acquittal. The trial thereupon came to a quick end. This tactic prevented Bryan from giving his summation at which he had been hard at work. Bryan was regarded as one of the greatest orators in the country and Darrow didn’t want to give him a chance to rehabilitate his position.

The Tennessee Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the statute based on the right of the state (i.e., the majority) as an employer of its teachers to tell them what to do. The Court denied that the statute impermissibly infringed on the separation of church and state in violation of the Tennessee Constitution, asserting that the law only prohibited the teaching of evolution. The Court pointed out that there was no unanimity about evolution among Protestants, Catholics or Jews and, for that reason, claimed that a law taking sides in the debate was not in the service of any religion. The Court didn’t directly discuss the Federal Constitutional requirements that church and state be separated, but its discussion of the similar state constitutional provision makes it clear where the court would have come out on that issue. However, on a minor technical ground, the Tennessee Supreme Court reversed the conviction. Finally, the Court pointed out that Scopes no longer taught school in Tennessee and stated that “We see nothing to be gained by prolonging the life of this bizarre case.” It then recommended that the case not be retried in the interests of the “peace and dignity of the state.” See Scopes v. State. No one other than Scopes was ever prosecuted under the Tennessee statute. It was repealed in 1967.

The trial was important, not because of the verdict or for any legal principals that it established, but rather it was a public relations battle for the mind of the country. While Darrow’s client was fined $100, Darrow was victorious in the public relations battle. The Scopes trial dealt a strong blow to creationism, fundamentalist religious beliefs, and majoritarian control over what teachers teach.

More than 200 newsmen covered the trial. International coverage was provided as telegraph operators sent reports through newly laid transatlantic cables. Reporters came from as far away as Hong Kong. Dayton became like a carnival with the streets full of “soapbox” orators, food sellers, and souvenir vendors. People who had strong opinions about the case converged on the town from all over the country. The side of the courthouse bore a large banner that read “Read Your Bible Daily!”

William Jennings Bryan, “the Great Commoner,” was a principled politician representing the agrarian wing of the progressive movement. He was the Democratic party’s candidate for president three times and should have held that office (one presidential election was stolen from him). Bryan advocated many reforms which were controversial at the time but most of which have now been adopted, including: the graduated income tax, the direct election of senators by the people, women’s suffrage, workman’s compensation, the minimum wage, the eight hour day, improved conditions for seamen and railroad employees, prohibition of injunctions in labor disputes, public regulation of political campaign contributions, government aid to farmers including minimum prices for agricultural products, government regulation of the railroads, telegraph and telephone industries, federal development of water resources, employment of safety devices, federal regulation of food processing, tariff reform, control of trusts, government control of currency and banking, government guaranty of bank deposits, the initiative, the referendum, defense of rights of minorities, anti-imperialism, including freedom for the U.S. colony in the Philippines, settling of international disputes through peaceful arbitration, support of education (including African-American education), strengthening of Latin American relations, excess profits taxes in time of war, and voting reform. While he was never elected president, history has shown that Bryan’s positions on the issues of the day were, for the most part, eventually enacted into law. The two most important exceptions are his advocacy of prohibition (enacted into law but later repealed) and his leadership of the anti-evolution crusade. But Bryan’s overall record of support for many progressive causes that were later adopted has assured him of a place in history.

Bryan served as Secretary of State under President Wilson from 1913 – 1915. In that office, he negotiated a series of international treaties by which countries agreed to arbitrate international disputes. These treaties foundered on the opposition of Germany and on the First World War. Bryan resigned from Wilson’s cabinet, opposing actions which he felt would inevitably lead to war with Germany. Outside of the government, he campaigned strenuously to keep America out of the war. But he recognized the right of the majority to make the decision between war and peace. Once war was declared, Bryan volunteered as a private in the Army. President Wilson declined to have Bryan serve in the army but enlisted Bryan in the public relations effort to sell war bonds, increase agricultural production and mobilize the country for war. Bryan served his country well in that capacity.

Bryan was one of the greatest orators ever produced by the United States. He was a newspaper editor and the author of 15 books as well as two anthologies of his speeches. After his political career was over, Bryan continued his public speaking and became a proponent of fundamentalist religion and a crusader against “Darwinism,” which he considered a threat to religious beliefs and morality. He lectured on creationism and other topics on the Chautauqua circuit. He wrote a syndicated “Sunday School” column which appeared in more than one hundred papers with more than 15 million readers.

Bryan’s guide, throughout his life, was a strong sense of Christian ethics. For him, the message of Christ was not merely preparation for the future world but a mandate for this world. Man’s task was not merely to remake himself and await salvation but to remake society and create an earthly salvation. War, alcohol (Bryan was a leader of the prohibition movement), greed and godlessness were not only to be resisted, they were to be smashed. Bryan was also a Populist. He believed that collective wisdom was superior to individual wisdom and that every man was capable of and worthy of directly participating in government. What was important was a man’s spirit, not his training.

Why would such a progressive politician try to prohibit the teaching of an accepted scientific theory in the public schools? The answer is that the Populist-progressive mind which Bryan exemplified was not particularly open or tolerant. Because the basis for its outlook was moral rather than pragmatic, the Populist mind did not seek for solutions, it knew the solutions. In his political and economic positions Bryan had been a consistent advocate of limiting individual freedom when it reached the point of becoming harmful to others. In the anti-evolution crusade, Bryan sought to limit freedom of the intellect when he thought it threatened religious beliefs and morality. In both spheres he was a moral crusader attempting to protect common people from what he conceived to be selfish and irresponsible forces. While most of Bryan’s political positions were ultimately adopted, the two crusades of the end of his life, prohibition and creationism, were ultimately unsuccessful and rejected by history. “… [I]f Bryan’s final years ended in tragedy, it was not the tragedy of a good man gone bad, but the tragedy of a good faith too blindly held and too uncritically applied.” (The description in this paragraph is adapted from Levine, Defender of the Faith, pages 358 & 359, 364 & 365; the quotation is from page 365.)

Bryan eloquently espoused the hopes and fears of the people of the rural South, West and Midwest. They, in return, looked upon Bryan as a symbol of what was good and right. As H.L. Mencken put it, after watching the reaction of a crowd to one of Bryan’s speeches, Bryan became “a great sacerdotal figure, half man and half archangel. In brief, a sort of fundamentalist pope.” H.L. Mencken, article July 14, 1925.

The picture of Bryan presented in the play and the film, while ultimately sympathetic, is in many ways inaccurate. Because of the focus of the story on the trial, it underplays his many accomplishments and his lifelong advocacy of progressive causes. His wife, Mary Bryan, was an invalid from arthritis and he took care of her. She had grave misgivings about his anti-evolutionist crusade and feared that it would evolve into a broad assault on freedom of speech and belief rather than simply an effort by parents and taxpayers to control what was taught in the public schools. Bryan promised her that he would not make that mistake. She then asked him if he could control his followers. He replied that he thought he could but shortly afterward, he died. (William Jennings Bryan and Mary Baird Bryan, The Memoirs of William Jennings Bryan, (Philadelphia, United, 1925) pp. 485 – 486). For an interesting comment on Bryan by a visitor to this site, see Comment to Learning Guide to Inherit the Wind below.

Bryan died five days after the trial from a long-standing illness, diabetes myelitis. He was very active during the last days of his life, keeping speaking engagements and arranging the publication of the closing argument that he did not have the opportunity to give at the trial.

A visitor to the site on July 19, 1999 sent us this comment:

First of all, you have a wonderfully informative and useful website. I did want to add one thing, though, about your analysis of the film Inherit the Wind (If this in there and I missed it forgive me.) What the film (as well as many depictions of the events) leaves out is that WJ Bryan feared evolution not just because it was at odds with creationism. He dearly feared that biological Darwinism would lead to social Darwinism or a “survival of the fittest” mentality. Evolution was also an attack, as he saw it, on the Social Gospel-portion of his theology. In this, Bryan was most prescient. The 1930s saw these fears realized in Nazi Germany where so-called lesser humans — Jews, the disabled — were deemed not fit to live. Given this, I hardly think the Scopes Trial should detract from the many great lifetime accomplishments of Bryan. Just a point of view you might want to consider adding to your analysis of the film.

There is a lot of merit to this comment. However, Byran’s fears were misplaced. To demonstrate this, one need only look at the strong democratic traditions of the U.S. and Western Europe in which civil liberties have co-existed with the theory of evolution for most of the 20th century. The spread of democracy to countries like India (1948), Japan (after the Second World War), and more recently to Turkey and to Indonesia (the most populous Muslim nation in the world) also demonstrate the strength of democratic ideals.

Constitutional cases usually involve a conflict between two sets of rights. In this case, the majority of the people of Tennessee through the state government asserted the right to tell the teachers that it employed what to teach in the schools owned and operated by the state. However, the Tennessee statute promoted the teaching of religious doctrine, creationism. The statute impinged upon the right of the people who disagreed with creationism to be protected from actions by the state supporting a religious doctrine. A similar statute was later struck down as unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court because it violated the separation of church and state. See Epperson v. Arkansas, 393 U.S. 97 (1968) and Significant Court Decisions Regarding Evolution/Creation Issues.

Clarence Darrow (1857 – 1938) was one of the most famous lawyers ever to practice in the United States. He was brilliant, tireless, and eloquent. Darrow specialized in defending the underdog. Frequently he took on cases for the poor and the extremely unpopular. Darrow stood for the rights of the individual against the majority and its efforts to make individuals conform, both in mind and action. He defended union organizers and labor leaders for decades against the arrayed power structure of the state and the powerful industries. Later, he undertook more criminal cases. Darrow did not believe in capital punishment and none of the more than one hundred defendants that he represented in capital cases were put to death. Darrow secured life sentences for the defendants in the infamous Leopold-Loeb trial. He also defended radicals subject to political prosecutions. Darrow had an enquiring and logical mind. He was extremely well read and fond of lively exchanges with the best minds in various fields of study. He frequently held “salon” evenings where there were spirited discussions covering a broad range of topics.

Darrow and Bryan had been on the same side on many issues before Bryan embarked on his anti-evolution crusade. Darrow ran for the House of Representatives in 1896, losing by 100 votes because he spent so much time that year campaigning for the Democratic Party’s presidential candidate, William Jennings Bryan.

Darrow, despite his well-known agnosticism, was considered a friend by many religious leaders. His religious friends often said that Darrow embodied the moral precepts of the Judeo-Christian religions in his actions. In his religious beliefs, Darrow maintained that while no one could prove the existence of God, no one could disprove it either.

When Scopes left Dayton to go to graduate school at the University of Chicago, Darrow (who lived near the University) took Scopes under his wing. He helped Scopes find an apartment and invited him almost weekly to the Darrow home. Scopes considered Darrow to be the second most influential man in his life after his father.

Darrow understood the intellectual process to be a search for truth. For this reason, fundamentalism dismayed him. The best way that he found to challenge fundamentalism was to show the intellectual weakness of its positions through Bryan, its leading proponent. As Darrow later wrote to Mencken “I made up my mind to show the country what an ignoramus he was and I succeeded.” (Larson, Summer for the Gods p. 190, quoting from letter Darrow to Mencken, August 15, 1925, in the H.L. Mencken Collection, New York Public Library, N.Y.)

Darrow’s career was not without controversy. His last labor case was the unsuccessful defense of the McNamara brothers in Los Angeles in 1911. The McNamaras were labor union officials who were accused of blowing up the Los Angeles Times building. The explosion claimed several lives. The McNamaras at first claimed to be innocent of the charges and victims of a conspiracy by the government and conservative interests to discredit organized labor. Labor unions and people from the left wing from all over the country rallied to the McNamara’s defense. Millions of dollars were raised. Darrow and a staff of investigators and lawyers were hired to represent them. The problem was that the McNamaras were, in fact, guilty. The information obtained by Darrow’s investigators all pointed to the McNamara’s guilt. Convinced that his clients would be convicted and subject to the death penalty, Darrow persuaded the McNamaras to accept a plea bargain in which their lives would be saved. Organized labor felt betrayed by the McNamaras and by Darrow. Darrow never tried a labor case again. After the plea bargain, Darrow was accused of complicity in attempts to bribe two jurors. The cases were tried separately. Darrow’s former allies in the labor movement would not help him and he was left to fight the charges with his own resources. Darrow was acquitted of the first charge and the jury hung 8 – 4 for conviction on the second charge. He was retried and eventually acquitted of the second charge. By that time Darrow was broken physically, emotionally, and financially. However, he was a resilient man. He returned to Chicago, rebuilt his law practice and his reputation. He went on to another brilliant career as a criminal defense lawyer. He capped off his work as a lawyer with the Scopes trial. (Some argue that Darrow was in fact guilty of bribing the jurors, despite the fact that he arranged a plea bargain for the McNamaras. See The People v. Clarence Darrow, Geoffrey Cowan, Times Books, 1993. We are not entirely convinced by this analysis, but it is intriguing and the book and the question is an excellent project for high school students with an interest in history.)

H.L. Mencken (1880 – 1956) was a journalist and author whose biting criticism was legendary. He was one of the most popular social critics of the 1920s and 1930s.

Claims of conflict between religious doctrine and science, while still generating hot debate in certain communities, have been much less violent in the 20th century than in prior centuries. In 1600, the Inquisition burned people at the stake for, among other things, believing that the earth revolved around the sun. The great Galileo Galilei, a father of modern science, escaped the same fate only by publicly recanting his belief in the Copernican system. The Inquisition was gentle with him. In return for denying a good part of his life’s work, Galileo was sentenced only to house arrest for the remainder of his life. For a perspective on claims of conflict between science and religion, see Learning Guide to “Contact”. For more on Galileo, see Learning Guide to: “Galileo: On the Shoulders of Giants”.

DIVERGENT CURRENTS IN AMERICAN THOUGHT EXEMPLIFIED BY THE SCOPES TRIAL IN THE WORDS OF THE PARTICIPANTS

The Scopes trial transfixed the country in 1925 and has fascinated Americans ever since. The philosophical and religious attitudes advocated by the participants represent legitimate choices and opinions strongly held by good and well-intentioned people. They include:

1) The right of the majority in any state to control what children are taught in the schools vs. academic freedom for teachers:

2) Fundamentalist religion which views the Bible as a source of knowledge about nature vs. religious beliefs which find no conflict between scientific discovery and belief in God and the Bible:

3) Reliance on tradition vs. willingness to accept the newest revelations of science:

4) The interest of a majority in any state in preventing the public schools from being used to teach scientific theories that contradict its religious beliefs vs. separation of church and state:

5) Belief that knowledge springs from the people vs. reliance on experts:

6) Creationism vs. the theory of evolution:

7) Regionalism v. nationalism:

The prosecution also tried to cast the debate in terms of a struggle between belief in God and agnosticism. (Bryan: “I am simply trying to protect the Word of God against the greatest atheist or agnostic in the United States. [Prolonged applause] … I want the world to know that agnosticism is trying to force agnosticism on our colleges and on our schools and the people of Tennessee will not permit it to be done. [Prolonged applause].” Bryan and Darrow at Dayton, page 151.) The position of the defense was that evolution did not conflict with biblical teachings.

In describing the events of the actual Scopes trial to children, be sure to tell them that the film departed from the historical facts so that the writers could comment on the problems of the Red Scares.

1. See Discussion Questions for Use With any Film that is a Work of Fiction.

2. In which court was Scopes tried, a court of law or the court of public opinion? Who won the Scopes trial?

Suggested Response:

The case was tried in both a court of law and the court of public opinion. The prosecution won a guilty verdict in the court of law. Darrow and the defense won in the court of public opinion and even today, with a resurgence of disbelief in the Theory of Evolution among the public, there is no substantial resistance to teaching the Theory of Evolution in the schools. Creationists now ask school districts to require disclaimers of the scientific accuracy of evolution or the teaching of alternative, allegedly “scientific”, concepts which they believe are more supportive of the biblical account. Recent court decisions have dealt defeats to this effort based on rulings that creationist theories have no scientific validity and are, in effect, an effort to introduce religious teachings in the schools. See Creationism and the Law from the National Center for Science Education. An additional winner in the Scopes trial was the city of Dayton which became famous as the location of the great debate.

The right of the majority in any state to control what children are taught in the schools vs. academic freedom for teachers.

3. Should there be a difference between the type of control exerted by the state legislatures over what professors can teach in publicly supported colleges and universities as opposed to primary and secondary schools which all children must attend?

Suggested Response:

The tradition of academic freedom in universities and institutions of higher learning is ancient. An important role of institutions of higher learning is to foster the creation and development of new ideas. Free and unhampered inquiry is prerequisite to the creation and development of new ideas. Students at these schools are adults and the theory is that they can be trusted to withstand fallacious ideas. For these reasons, academic freedom is an important value in the college and university setting. The public schools, in which childen are being trained in the basic skills and values of society, are not involved in the creation and development of new ideas. Within certain limits, the legislatures can dictate the course of study in elementary and secondary schools. Public school children are very impressionable and there is no need for free and unhampered inquiry into new ideas in their schools.

However, even in the public schools, the control of the majority, as expressed through the legislature, is not unlimited. In the U.S., one of the limits is that the state cannot foster the doctrines of any religion or promote any religious belief. This doctrine is called the separation of church and state and it’s enshrined in the First Amendment to the Constitution. It was made applicable to the states by the 14th Amendment.

4. In the United States and other constitutional democracies, what is the source of the limits on the rights of the majority, acting through their elected officials?

Suggested Response:

Consitutions set out limits on the rule of the majority. For example, the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution provides that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” This applies to the states by virtue of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Fundamentalist religion which views the Bible as a source of knowledge about nature vs. religious beliefs which find no conflict between scientific discoveries and belief in God and the Bible.

5. Are the biblical accounts of creation and of the miracles literally true?

Suggested Response:

This question is related to religious belief. Public school teachers probably shouldn’t get into it. Parents should discuss this issue with their children in light of their own religious tradition.

6. Is the theory of evolution inconsistent with the biblical account of creation, or, does science merely show how the universe was created without reference to whether it was created by God or by chance or by any other agency?

Suggested Response:

This is a question related to religious belief. Public school teachers probably shouldn’t get into it. Parents should discuss this issue with their children in light of their own religious tradition.

Reliance on tradition vs. willingness to accept the newest revelations of science

7. In making decisions, what is the proper role for expertise, what is the proper role for common sense, and what is the proper role for tradition? — To advance the discussion of this question, teachers should give the class the following background.

(1) The answer to this question is complicated by the fact that the experts change their positions. Often we read in the newspaper about some new scientific study which shows that practices that doctors had recommended in the past are actually harmful. The change in expert scientific opinion can apply even to fundamental laws of the universe. Newton’s “clockwork universe” held sway for hundreds of years until science’s view of the laws of physics were substantially changed by Einstein’s theory of relativity. Darwin’s Theory of Evolution is one of the most thoroughly tested and confirmed scientific theories that has ever existed. The acid test for a scientific theory is whether or not it suggests hypotheses which can then be tested through experiment or observation. Scientists have verified hypotheses predicted by the Theory of Evolution thousands, perhaps millions, of times. However, all scientific theories are tentative in the sense that they all are subject to being refined or even overthrown by new observations or experiments. Look at what happened to the theories of Newton.

(2) On the other hand, scientists aren’t talking about changing their view of nature to conform to myths or religious texts. Scientists are talking about changing and refining theories to take account of newly discovered facts or the results of new experiments. Nor are they talking about chucking the scientific method, one of the greatest inventions of mankind. The scientific method has yielded amazing results and ranks close to the development of language or the use of tools in its contributions to the quality of human life. Without science, we would not have discovered that diseases were caused by germs and viruses. Without science, we would still be using horses to get around. Without science, there would be no computers, CDs, DVDs, MRIs, CT scans, antibiotics, sky scrapers, or modern sanitation systems. Yet, for centuries, religious authorities fought basic scientific discoveries, such as the idea that the earth revolves around the sun. Galileo was required by the Inquisition of the Catholic Church to recant his scientific discoveries.

(3) People often hold themselves out as experts about questions in which there is no clear scientifically verified answer. Examples are: many questions of medicine; handwriting analysis; fingerprint identification; etc. Experts can often only give us the best-educated guess of the people who have studied their field. Experts have, in the past, maintained some obviously incorrect positions. They told us the earth was flat and that witches can fly on broomsticks.

Now, ask the question again and see what the students say.

Suggested Response:

There is no one correct answer. One point that the discussion should cover is that in evaluating an expert’s opinion or advice, we should try to find out how much of it is based on scientific testing.

8. Is there an inevitable conflict between science and religion? Justify your position.

Suggested Response:

This is a question related to religious belief. Public school teachers probably shouldn’t get into it, other than to help students with the three points set out in the preceding question which relate to an understanding of the scientific method and its contributions to society. Framing a complete answer to this question should be left for students to resolve in conversation with members of their families.

The interest of a majority in any state in preventing the public schools from being used to teach scientific theories that contradict its religious beliefs vs. separation of church and state

9. Should the majority be able to use the public schools to transmit their religious values to their children or must the majority be prevented from doing this to preserve the separation of church and state?

Suggested Response:

The majority cannot use public schools to transmit their religious beliefs. This is an unconstitutional promotion of religion by an agency of the state. Epperson v. Arkansas, 393 U.S. 97, 105. In that case, a statute very similar to the statute involved in the Scopes case was struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court.

10. Should the state tell people what to believe? What about concepts such as honesty, drug education, patriotism, obedience to the rule of law, concern for others, and resolving disputes peacefully? Most agree that these concepts should be taught in public schools. Why can the state, through its teachers and schools, tell children what to believe in matters of civics and basic morality but not in matters of religion?

Suggested Response:

The basic precepts of morality are shared by all major religions. For example, The Six Pillars of Character are shared by Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. They are also adopted by non-religious ethical humanists. We haven’t studied the matter but we also believe that they are not inconsistent with other major religions including Hinduism and Buddhism. For a democracy to work, its people must share certain ethical beliefs. In addition, schools can’t function if people don’t agree upon such things as honesty, responsibility, and tolerance. It is a proper function of the schools to teach these beliefs.

11. In the Scopes trial, the legislature, acting for the majority, wanted to prevent the teaching of a scientific doctrine that it felt was inimical to its religious beliefs. Does this violate the separation of Church and State?

Suggested Response:

Yes. Epperson v. Arkansas, 393 U.S. 97, 105. In that case, a statute very similar to the statute involved in the Scopes case was struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court.

The belief that knowledge in springs from the people vs. reliance on experts

See Question # 7 above.

Creationism vs. the theory of evolution

13. Does the theory of evolution contradict the biblical story of creation?

Suggested Response:

This is a question related to religious belief. Public school teachers probably shouldn’t get into it. This question is for students to resolve in conversation with members of their families. See Question #7, above.

14. Is it true that once a person accepts that some stories in the Bible should not be taken literally, that there is then no justification for any story in the Bible being taken literally?

Suggested Response:

This is a question related to religious belief. Public school teachers probably shouldn’t get into it. This question is for students to resolve in conversation with members of their families.

Regionalism vs. nationalism

15. Can one region of the country have a different interpretation of science than other regions?

Suggested Response:

No. Scientific discoveries are universal and apply everywhere.

16. Can one region of a country have a different interpretation of a basic constitutional provision than the rest of the country? What would happen if this was permitted?

Suggested Response:

No. The constitutions should be interpreted in the same manner in all parts of the country. Otherwise, there would be no rule of law.

Discussion Questions Relating to Ethical Issues will facilitate the use of this film to teach ethical principles and critical viewing. Additional questions are set out below.

(Be honest; Don’t deceive, cheat or steal; Be reliable — do what you say you’ll do; Have the courage to do the right thing; Build a good reputation; Be loyal — stand by your family, friends, and country)

1. Do you think that in the Scopes trial, both Clarence Darrow and William Jennings Bryan were following the Pillar of Trustworthiness? Justify your position and, if your answer is “yes,” describe how this could be true for two men with diametrically opposing viewpoints.

Suggested Response:

Yes. Both Bryan and Darrow were advocating heartfelt beliefs that they thought were correct. They were both being truthful.

(Do your share to make your school and community better; Cooperate; Stay informed; vote; Be a good neighbor; Obey laws and rules; Respect authority; Protect the environment)

2. Do you think that in the Scopes trial, both Clarence Darrow and William Jennings Bryan were complying with the requirements of the Pillar of Citizenship? Justify your position and, if your answer is “yes,” describe how this could be true for two men with diametrically opposing viewpoints.

Suggested Response:

Yes, both Bryan and Darrow were advocating heartfelt beliefs that they thought were correct. In a democratic society, just because a person takes a position that is different from yours, even on basic issues, doesn’t mean that he or she is not a good citizen.

See Assignments, Projects, and Activities for Use With Any Film that is a Work of Fiction. Debates among class members can be staged, scenes from the movie can be re-enacted, and the logic of the opinion in Scopes v. State can be compared with the logic of Epperson v. Arkansas.

Books recommended for middle school and junior high readers include Center of the Storm, by John T. Scopes and James Presley.

In addition to websites which may be linked in the Guide and selected film reviews listed on the Movie Review Query Engine, the following resources were consulted in the preparation of this Learning Guide: