Thoughts About Discussions of Racism in America – Understanding the Meaning of Black Lives Matter

This Learning Guide is being written in the early summer of 2020, during the Black Lives Matter demonstrations following the killing of George Floyd. What follows are some thoughts that might assist teachers in discussions with their classes.

Why should a person not be a racist? Some say that they are not racist in order to be fair to others — they contend that it is unfair to treat people of another race differently than people of one’s own race. While this is undoubtedly true, and it is certainly important to treat people fairly, recognizing people’s rights and, more broadly, fully including them within the circle of moral concern, is more fundamental than just being fair. The idea of not being racist in order to be fair accepts the concept that there is an US and a THEM and a difference between US and THEM, that through compliance with a moral duty, we ignore. However, recognizing our unity with other human beings is more fundamental than the fulfillment of a duty to be fair to others.

In addition, such an attitude implicitly acknowledges the “otherness” of the different race. There is danger there. The concept of “the other” has been the justification of much pain and death throughout history. The Nazis classified Jews, Slavs, the Roma, political opponents, the very religious, and the handicapped as the “other” and felt justified in killing twelve million people – roughly six million Jews and six million “others.” In the Rwandan genocide, the Hutu called the Tutsi “cockroaches” as they slaughtered men, women, and children with machetes, in the hundreds of thousands. Thus, even when coupled with a recognition of the moral obligation to be fair, the implicit acceptance that a race of human beings are “others” is problematic.

A better reason to reject the superficial classification of race, arises from an understanding of the equivalence of all races in their humanity, that is a recognition that: “WE ARE THEM” and “THEY ARE US;” that we are all equivalent in our humanity. Thus, being free of racism is a celebration of being human rather than an ethical obligation.

Unfortunately, its not quite that easy. There is a legacy of racist attitudes in society that most people absorb, to one extent or another, as they grow up. Even people who believe themselves to be free of prejudice, unconsciously absorb some of these attitudes. Getting rid of them is a process that is sometimes difficult and will take us out of our comfort zones. It is a process that takes years and can be lifelong. It has been likened to peeling an onion: you take away one layer and think you have dealt with your prejudice, only to find another aspect lurking in the next layer. You take away that layer and feel triumphant, only to discover, perhaps years later, another layer of prejudice to that you want to resolve.

Why go through this process? The reason is that when we fully realize the unity of all human beings, that “I = YOU, all of YOU,” many people will experience a step up in the level of their consciousness, an improvement in their state of being. Instinctively, most people feel good at greater connection to others and this feeling is magnified when extended to a larger group. It becomes a source of joy that when fully realized, it lasts a lifetime — it never goes away. Thus, a primary beneficiary of a person’s rejection of racism and the extension of the zone or moral concern to all people is the person him or herself.

Not only does an inclusive person who rejects racism and division have an additional source of joy in their life, but discarding racist attitudes, and recognizing that all people are within the zone of moral concern, allows us approach being the best person we can be. As we live a life of inclusion and root out the vestiges of racism we improve, perfect, and save ourselves.

Differences of race, gender, ethnicity, sexual preference, religion or political affiliation are superficial and our common humanity is a much stronger and more important factor in any debate. There is a natural tendency in human psychology to want to have common ground with the people with whom we associate. Those ties will be strengthened by looking for deep and important similarities rather than focusing on the superficial. For example, there are nurturing people of every race. There are law-abiding people of each of these groups and lawbreakers in each of these groups. There are honest people in every group. Who would you like to be with? People of a different race who are nurturing, law-abiding, and honest or people of the same race who are not. These are some of the more profound differences, but even in less important aspects of life, race is less important than what unites us. For example, some people in each racial group love their hometown sports teams and love to attend or to watch their games. There are others who have no interest in sports. Would you rather watch a game of your favorite sport with someone who really gets into it and shares your knowledge and enthusiasm, or would you rather watch the game with someone who just doesn’t care and is bored out of his mind. If you loved the newest music craze would you want to attend a concert with a person who thought that your favorite band was just a lot of noise?

Being non-racist means that we accept all people as our brothers . . . and this naturally leads to activism, because we cannot sit idly by while our brothers are being oppressed. And this means not only that the lives of all our human brothers and sisters matter, but that it is important to emphasize that George Foreman’s life matters– that in this moment in American history — that Black Lives Matter.

And as for the police, I for one am profoundly grateful to the vast majority of policemen and women who every day put their lives on the line to protect me and my family. There are bad people about in the world and the law abiding need protection from them; we rely on the police for this. In addition, some of the police shootings of black men appear, on close and careful analysis, to have been justified or to be “suicide by cop” a problem that transcends all races and has been around for a hundred years.

However, somehow, the culture of policing has veered toward a warrior culture — or perhaps it always had aspects of that culture and as society has evolved to be less racist, that mode of policing is no longer accepted. But the killing of George Floyd clearly shows that policing in America needs reform.

___________________

A General Principle of Discussion: In any discussion of a sensitive topic, the key perspective should be the many things that unite all human beings: love of family and friends, an innate sense of justice, desire for acceptance, a desire for liberty, even a love of good food and having fun. The traits that unite us are much stronger than anything that divides us, be it race, gender, national origin, sexual preference, religious belief, or political affiliation. All of the different groups in America have made important contributions to the country. This is basic but given all the propaganda and the internet bots that focus on division, it is helpful to restate this principal.

Some Specific Thoughts:

The utter idiocy of racism is shown by the one-drop rule. Traditionally, if you had one drop of black blood in your veins — one black ancestor many years ago — you were considered black racially. The purpose of this had to have been to retain white racial purity at a time when white superiority was thought necessary to justify slavery. This false and pernicious distinction has become translated into the American society and is one of the more pernicious holdovers of slavery (on a par some would say with the electoral college and the U.S. Senate, remnants from the original design of the U.S. Constitution to protect slavery). Everyone knows “black” people whose ancestry is clearly almost entirely white, and yet society classifies them as African American. However, the better way to view people, is that they are just that, people.

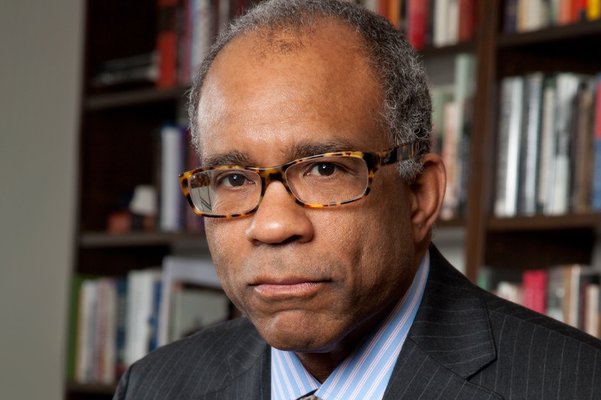

TWM recommends showing the four-minute film clip of attorney Bryan Stevenson and actor Michael B. Jordan appearing on The Ellen Degeneres Show. Click here for a partial transcript. TWM agrees that the U.S. should have, as Mr. Stevenson suggests, a period of truth and reconciliation about racial discrimination. Anyone who lived in the South during the time of Jim Crow laws (1870s to 1960s – 90 years), as did this author from 1950 to 1969, knows that the way that most whites treated blacks in that time was shameful. In addition, there was race-based discrimination throughout the rest of the country during that period. Moreover, elements of racism still exist in the U.S. On the whole and with some exceptions, life is easier in the U.S., to one degree or another, if you are white than it is if you are black.

Here’s a question for debate. The Federal government maintains a wonderful historical park at the site of the battle of Gettysburg, one of the great victories of the Union Army over Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Back in the late 1800s and early 1900s in its efforts to reunify the country, the federal government allowed states and people from the South to erect more than 20 statues to Confederate generals and Army of Northern Virginia units in the park. Should these statutes be removed or stay in the historical park?

Monuments to Confederate Generals and office holders were permitted by the federal government after the Civil War to help reunify the country after a bitter and, for the South, devastating conflict. However, they soon became symbols of racial oppression – which is what they are today. They should be destroyed or relegated to museums in exhibits showing examples of racial oppression.

Hundreds of Thousands White Union Soldiers Died in a Civil War that Became a Crusade to Abolish Slavery. When the Civil War began in 1861, most Northerners supported the war to preserve the Union, not to abolish slavery. At that time, most of Europe was in the hands of a resurgent aristocracy and the democratic promise of the French Revolution was in retreat. The U.S. was the world’s only major representative democracy. If the U.S. could not hold itself together the cause of democracy, not only in America but in the World, would have been set back for generations, if not discredited entirely. However, for the South, despite its states’ rights rhetoric, the war was always about slavery; the Confederates knew it and they said it. And, as the war progressed and the casualties mounted by the hundreds of thousands, the Union came to realize that the only justification for such a great sacrifice was the abolition of slavery. The Union death toll in the Civil War is now estimated to be 750,000, of which 40,000 were African-Americans, allowed to fight only towards the end of the war. More Union soldiers died in the Civil War than U.S. armed forces have died in all other wars combined. Hundreds of thousands of these men fought to end slavery.

While the paroxysm and the bloodletting of the Civil War have gone a long way to purge the country of the sin of slavery, there remains the need to deal with 90+ years of Jim Crow and the continuing discrimination against African Americans by some Americans and by some American institutions.

The class can read what Mr. Stevenson wrote about one aspect of living as an African American in the U.S.

Because I am black, I am automatically accused of seeing racism in every problem, and that is interesting to me because I spend most of my time desperately trying to find a way to see something other than race. . . I keep looking for a place where race isn’t an issue, where you can rule out race as being responsible for anything bad that happens to you and also discount for anything that is good. A place where you can live like any normal human being. The tragedy is that you spend a lot of time trying to deny things that are race-based because you would rather not believe it. I would rather believe that the investigators and the Monroeville community [who wrongfully condemned Walter McMillian] just made a mistake and if Walter McMillian were white, he would be in the same situation as he is in now—if Ronda Morrison had been black, that the same thing would have happened. I would think more highly of that community if that were true, but the bottom line is that I can’t convince myself that it is true, and it doesn’t help black folks or white folks to act like it is true if it is not. Earley pg. 394.