27 Student Reports: In preparation for showing the movie, have students present short reports on the following topics. If a particular report does not include the “Important Facts,” teachers should supply the missing information along with any additional insights that the teacher believes will be helpful. For a list of report topics click here. Omit reports on those topics that the class has already studied. In the alternative, teachers can provide the necessary background for the film through direct instruction using the “Important Facts” as the starting point for the lecture.

The End of Slavery in Great Britain and the British Empire

Important Facts:

In 1772, four years before the American Revolution, England’s highest ranking judge ruled that the Common Law did not allow slavery and that since there was no statute permitting slavery on English soil, no slave could be held against his will. The case concerned James Somerset, a slave brought to England from Virginia by his master. Somerset ran away but was captured and confined on board a ship that would soon sail for Jamaica where Somerset was to be sold. Friends of Somerset filed an application in the English courts for a writ of habeas corpus. Lord Chief Justice Mansfield issued the writ requiring the captain of the ship to bring Somerset to the court and to justify his detention. Somerset’s master appeared in the case and tried to claim his “property.”

Lord Chief Justice Mansfield noted that, “The power of a master over his slave has been exceedingly different, in different countries.” He held that since common law judicial decisions had to be based on the values of the community and since for the people of England slavery was “odious,” Somerset could not be held in slavery under the common law. The only other way for slavery to be imposed in England was by positive law, that it is, by a decree of the King or a law passed by Parliament. Since no such positive law permitting slavery existed in England, Lord Mansfield held there was no basis to deny Mr. Somerset his freedom. This decision effectively abolished slavery in Britain because any slave who ran away could not be compelled to return to his or her master. The Somerset decision was known to the slave owners in the American South. While it only applied to slaves in the British Isles, the handwriting was on the wall, and slave owners worried that eventually slavery would be outlawed throughout the British Empire. Thus, in addition to their desire for a republican form of government, the Southern slave owners had another contradictory reason for joining the American Revolution; ensuring that the benefits of freedom did not apply to their slaves.

The prediction of Southern slave owners that slavery would be banned in the British Empire proved correct. After years of abolitionist protests the international slave trade was outlawed by Great Britain in 1807 and slavery was abolished in most of the Empire by 1833.

The Role of Slavery in the American Revolution and the South’s Bargain with the North to Protect Slavery

Important Facts:

In 1776, the cause of abolition was gaining strength in the United Kingdom. Slavery in Britain itself had been effectively abolished by judicial decision in 1772 in Somerset’s Case. In 1776 when the South joined with the North to declare independence and also in 1787, when the constitution was drafted, it was apparent to the planter class in the Southern states that the British Empire was moving to abolish slavery in the colonies. The Southern Colonists agreed to participate in the American Revolution, in large part, to avoid the abolition of slavery and required the North to agree to let slavery alone if the nation and later the Constitution was to come into existence. Southern concern over the fate of slavery in the British Empire was well-founded. Britain outlawed slavery in the colonies in 1833.

Constitutional Protections for Slavery

Important Facts:

The original Constitution never used the words slave, slavery, involuntary servitude, or bondage. However, there were several provisions that protected slavery. Art. I, Section 2, Clause 3 prohibited Congress from banning the importation of slaves until the year 1808. Article 4, Section 2, Clause 3 protected slavery even in free states: If a slave escaped to a free state, his status remained that of a slave, and he had to be returned. The Three-Fifths Rule provided that each slave was to be counted as three-fifths of a person in determining representation in the House of Representatives and votes in the Electoral College, although only whites could participate in elections. This gave the South a strong advantage in Congress and a disproportionate say in the election of the President. Finally, Article V, which required that amendments be proposed by 2/3rds of each House of Congress and ratified by 3/4s of the states, indirectly, protected the other pro-slavery provisions of the Constitution by making it impossible to amend the Constitution without the agreement of the South.

In short, at the request of Southerners, the framers of the Constitution built several layers of protection for slavery into the framework of government. Northerners agreed to these provisions for the purpose of getting the Constitution adopted, expecting that the institution of slavery would wither away. In 1776 and 1787, with the slave economy under stress, that appeared to be happening.

Many northerners who were opposed to slavery recognized that it was protected by the Constitution in the slave states. These included Lincoln (see his First Inaugural) and even such radical anti-slavery men as Thaddeus Stevens. See Korngold, 47 and Excerpts from the debate on the 13th amendment.

Some of the Consequences of Slavery for the Slave, the Master, and Southern Society

Important Facts:

Life-long servitude and status as property sometimes deprived slaves of “life” and always took away their “liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” Examples include loss of the following: the right to the fruits of their labor; the right to maintain a family (raise their children, choose a spouse, and live with that person); the right to choose an occupation; freedom from undeserved punishment; the right to defend oneself from aggression by the master or by white men; access to justice in the courts, and, primarily for women, the right to resist sexual advances by white men. In addition, slaves were prohibited from becoming educated. In every slave state except Tennessee, slaves were not permitted to learn to read or write.

For the masters, the power over slaves contributed to the following: it denigrated the value of work (if a slave could do it, the task was too menial for a white man); loss of empathy and indifference to the suffering of others by being the agents and beneficiaries of the denial of the slaves’ liberty (e.g. while it’s much worse for the slave family, the person who causes the family to be split up or who stands by and profits from it becomes hardened and less empathetic to others); sadistic tendencies (e.g., beating slaves or having them be whipped to coerce obedience); for the white men who had sexual relations with slave women, the act diluted if it did not destroy the meaningfulness of sexual relations with their wives and required them to deny any affection for the children born of their sexual exploitation of female slaves.

For Southern society slavery denigrated the value of work, led to a division of wealth in favor of the planter class, and retarded the development of industry, which is one of the reasons why the South lost the Civil War against a much more industrialized North.

George Washington and Slavery

Important Facts:

Although George Washington owned slaves most of his life, he supported the gradual abolition of slavery. In fact, in his will, he freed his slaves upon the death of this wife Martha, and established a trust fund to assist them in the transition to lives as free men and women. Washington was the only founding father to free his slaves.

Washington signed the law in 1790 that reaffirmed the ban on slavery in the Northwest Territory, but he also authorized military and financial aid to Haitian slaveholders during the revolt by slaves in Haiti in 1791. Washington also signed the nation’s first fugitive slave law allowing for the capture of slaves who had fled to northern states.

Thomas Jefferson and Slavery

Important Facts:

Thomas Jefferson understood the evil of slavery and proposed ending the practice all of his life. Jefferson’s first draft of the Declaration of Independence included the following passages among the list of outrages by George III. [The phrases in brackets are changes either by Jefferson or by John Adams. Note that at the time of the Revolutionary War, the British were offering freedom to slaves who turned on their masters and joined the British Army.]

[H]e has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating it’s most sacred rights of life and liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating and carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere, or to incur miserable death in their transportation hither. this piratical warfare, the opprobrium of infidel powers, is the warfare of the Christian king of Great Britain. [Determined to keep open a market where MEN should be bought and sold,] he has prostituted his negative for suppressing every legislative attempt to prohibit or to restrain this execrable commerce … and that this assemblage of horrors might want no fact of distinguished die, he is now exciting those very people to rise in arms among us, and to purchase that liberty of which he had deprived them, by murdering the people upon whom he also obtruded them: thus paying off former crimes committed against the liberties of one people, with crimes which he urges them to commit against the lives of another.

This clause was deleted at the behest of the Slave Power in the Continental Congress.

However, Jefferson did not believe in freeing slaves as a general rule because he thought that it led to insurrection or race war. Jefferson wrote that slavery was like holding “a wolf by the ear, and we can neither hold him, nor safely let him go.” As Secretary of State Jefferson wrote the Northwest Ordinance that prohibited slavery in the Northwest Territories.

Slavery financed Jefferson’s very expensive life-style. Jefferson freed only a few slaves, including Sally Hemings’ two older brothers and her children. Sally Hemings and another slave were informally freed at his death by Jefferson’s daughter who gave them “their time.” The rest of Jefferson’s slaves were sold at his death to pay his debts.

Jefferson has been strongly criticized for his unwillingness to free his slaves during his life or at his death.

Benjamin Franklin on Slavery

Important Facts:

Early in his adult life, Franklin owned two slaves, an accepted practice in Philadelphia at the time. He assumed, as was the common belief, that Africans were sub-human. This began to change in 1759 when he visited a school for young blacks and observed that they were studious and intelligent. Over time his attitudes toward slavery and blacks changed and he began to see slavery as a system that caused black degradation. Franklin freed his slaves and, in 1770, began to attack the institution. When Franklin returned from France in 1785, he became President of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery and the Relief of Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage. However, in 1787 he supported the new constitution that accepted and protected slavery. Otherwise, for the rest of his life Franklin was a participant in efforts to abolish slavery.

How Northern Ingenuity Strengthened Slavery in the South and Help Set the Preconditions for Civil War

Important Facts:

Before 1794 cotton was not a particularly profitable crop in the American South. It could have been. Cotton doesn’t spoil and even before refrigeration could be easily stored for long periods and shipped long distances. However, cotton has small black seeds intermixed with the cotton fibers. Even with slave labor it was difficult and time-consuming to remove the seeds. This changed when Eli Whitney (1765-1825) an inventor from Westboro, Massachusetts, invented a machine that automated the separation of cottonseed from cotton fiber. A cotton gin could generate up to fifty-five pounds of cleaned cotton daily. Suddenly, cotton production became profitable, cotton cultivation expanded, and there was an increased demand for slaves to work the cotton fields. A thriving textile industry grew up in New England and in Britain to turn Southern cotton into cloth for the American and European markets. This changed the economy of the American South, strengthening the economic foundation of slavery. The cotton gin was one of the key inventions of the industrial revolution. Cotton came to represent over half the value of U.S. exports from 1820 to 1860.

Before the invention of the cotton gin, slavery was on the decline in the South and many of the Founding Fathers expected that it would eventually whither away no matter how many protections it had in the U.S. Constitution. However, with the invention of the cotton gin and the vast expansion in the cultivation of cotton, the wealth and power of the Southern planter class increased. This led to what abolitionists and Republicans called “the Slave Power.” In this indirect way, a Yankee inventor was a major contributor to the political and economic power of the slaveholders.

The cotton gin was widely copied and Eli Whitney was unable to make money from his invention. However, he did become famous. This helped him get a contract to manufacture muskets for the U.S. Army. To fulfill the contract, Whitney invented a system for manufacturing muskets by machine, making the parts interchangeable. This led to faster assembly and easier repair. For this work, Whitney became famous again as a pioneer of American manufacturing. He also made a fortune. Eli Whitney continued to create new inventions for the rest of his life.

The Political Power of Slaveholders Before the Civil War

Important Facts:

“Slavery . . . was the most powerful institution in the nation from 1830 to 1860 . . . . It elected every President of the United States, except four, until the new era. It completely dominated the Senate and the Supreme Court, and nearly every Congress prior to 1861. West Point was ancillary to it; both the army and the navy were its auxiliaries. The social life at Washington obeyed its behests; . . . Statesmanship was its servitor; and diplomacy its handmaid. Exponents of the effete Southern aristocracy swarmed in the departments. . . ” Henry C. Whitney, a friend and biographer of Lincoln, writing nearly four decades after Lincoln’s death. From Life on the Circuit with Lincoln, pp. 376-377 by Henry Clay Whitney.

Before the Civil War, ten of the fifteen Presidents owned slaves and some of those who didn’t, such as James Buchanan and Martin Van Buren, were beholden to or associated with the Slave Power. One of the reasons why the national capital wasn’t located in the population and commercial centers of the North, such as New York and Philadelphia, was that those states restricted slavery. Instead, it was carved out of two slave states, Virginia and Maryland. Slavery was legal in Washington, D.C. until 1862.

In 1860 “[t]he economic value [the slaves], when considered as property, exceeded the combined worth of all the banks, railroads, and factories in the United States. In geographical extent, population, and the institution’s economic importance, the [American] South was home to the most powerful slave system the modern world has known.” Foner, p. 17

What Life was Like for Free Blacks in the U.S. Before the Civil War

Important Facts:

It depended upon where they lived. In many places, North and South, free blacks couldn’t vote or hold public office nor could they travel or live where they pleased. Some states prohibited the entry of free blacks. In most states free blacks were subject to seizure as fugitive slaves. In some states they were prohibited from owning real estate, testifying against whites, entering into contracts, maintaining lawsuits or enrolling their children in school. Free blacks in the South were under the most restrictions. In some places they were not permitted to assemble even for religious services. Tsesis, pp. 21 & 22.

Attitudes Toward Slavery in the South from the time of the Revolution through 1865

Important Facts:

At the time of the Revolution many leaders of the South, including Founding Fathers George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Monroe, and James Madison disliked slavery and were aware of its evils. However, they couldn’t figure out a practical way to end slavery. As the production of cotton and slavery became more profitable and abolitionists became more strident in their denunciation of slavery, Southerners reacted by elevating slavery to a God-sanctioned necessity for a civilized nation. Local voices against slavery were severely punished and therefor stilled.

The Abolition Movement in the U.S.

Important Facts:

Vermont abolished slavery in 1777, and by 1804 all of the other Northern states had done the same. In most states, emancipation was gradual, with, for example, no living adult slaves being emancipated but children attaining freedom after working well into adulthood. Foner, pp. 14 & 15. However, the movement to abolish slavery nation-wide did not gain momentum until the 1820s. Abolition came to the fore as the Great Awakening accelerated. America during this period came to celebrate individualism and the self-made man who rose from humble beginnings to wealth and positions of prominence. (Abraham Lincoln and Thaddeus Stevens were self-made men who grew up in poverty.) Some Americans, like Lincoln and Stevens, disliked slavery and believed in free labor. They believed that a person should be able to benefit from the fruits of his labor. In that environment, the fact of slavery became all the more galling, and the immorality of slavery began to penetrate the consciousness of some people in the North.

The aim of the abolitionist movement was to alter public opinion and bring about a much needed moral transformation among white Americans so that they recognized the inhumanity of slavery and that all people should be equal before the law. Most abolitionists also believed in racial equality. Foner, p. 20. By that standard, the abolition movement was only partially successful, achieving freedom for blacks but not its other goals. Equality of all races before the law and the moral transformation that eliminates racism is still a work in progress.

Many Americans, including Lincoln and his idol, Henry Clay, wanted to colonize the slaves in Africa believing that the two races could never live together in peace. As late as 1862, Lincoln was proposing colonization. However, the idea died because, very simply, freed African-Americans didn’t want to leave the United States. Foner, pp. 19 & 130.

While the abolitionists made gains from the 1820s onwards, at the beginning of the Civil War most Americans were not abolitionists and most Northerners would have let the Southern states keep enslaving blacks. Unlike the abolitionists who wanted a complete ban on slavery, Lincoln’s position, and that of a majority of the North in the 1860 elections, was that the Constitution protected slavery in the South. What they were against was the expansion of slavery into new territories.

In fact, most Americans disliked abolitionists, either they supported slavery or they feared abolitionists would drive the South out of the Union. Working class whites feared that free blacks would come North and take their jobs. Abolitionist meetings were often disrupted by crowds of angry whites, and occasionally abolitionists were killed. During the war, there were riots in New York in which blacks were hunted down and killed. Lincoln, despite his antipathy to slavery, repeatedly distanced himself from the abolitionists, understanding that identification with abolitionism would be a great obstacle to Republican success at the polls. Until emancipation of the slaves in the South became a military necessity, Lincoln advocated leaving slavery alone in the South. As the war continued, Lincoln came to adopt the abolitionist position on freedom for African-Americans, if not on the equality of blacks and whites. Foner, p. 24, 25 & 89 – 91.

The Dred Scott Decision

Important Facts:

Dred Scott was a slave from Missouri whose master, an army doctor, had taken him to live in the free state of Illinois, then to the free territory of Wisconsin, and finally back to the slave state of Missouri. With his wife and two daughters (ages 14 and 7 at the time of the Supreme Court ruling), Scott brought a lawsuit claiming that since they had resided in a free state and a free territory, they were now free even though they had been moved back to Missouri, a state that recognized slavery.

Chief Justice Roger Taney, who wrote the opinion of the Supreme Court, was from an old planter family in Maryland; he had manumitted his own slaves in the 1820s. However, he was a firm believer in black inferiority. In the Dred Scott decision, the Court had held that all blacks, including free men, were not citizens of the United States and never could become citizens. It held that the words “all men are created equal” in the Declaration of Independence did not apply to blacks. The decision found that African-Americans were considered merely as property by the Founding Fathers.

Thus, blacks, slave and free, could not be citizens of the United States even if a state made them citizens and granted them certain rights. Those rights would not extend beyond the bounds of the state. Six of the other eight justices joined in Judge Taney’s decision, thus the vote on the case was 7 to 2.

In the Dred Scott decision, the Supreme Court also ruled that Congress had no power to outlaw slavery in the territories. Click here for excerpts from the Dred Scott decision.

Justice Taney had hoped that the decision in the Dred Scott case would settle the issue of slavery once and for all. Instead, the ruling angered the North, emboldened the South, and indirectly helped to cause the Civil War. Foner, pp. 92 – 94. It is now regarded as the worst decision ever made by the U.S. Supreme Court and was effectively overruled by the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments.

The Election of 1860

Important Facts:

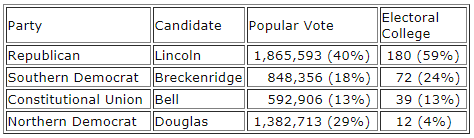

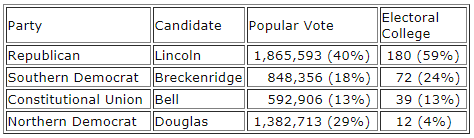

Seward expected to be the Republican nominee for President in the 1860 elections, but Lincoln was more moderate on slavery, pledging to leave slavery alone in the states in which it was legal but to prevent its expansion into the territories. He was viewed as more electable than Seward precisely because of his position on slavery. The Democrats split into a Northern faction which supported Stephen A. Douglas and favored popular sovereignty and the Southern Democrats who contended that under the Constitution Congress could not forbid slavery anywhere (see the Dred Scott decision). A fourth party, the Constitutional Union party of John C. Bell, didn’t take a position on slavery but supported maintaining the Union.

Republicans campaigned on halting the expansion of slavery. They downplayed the threat of secession contending that it was not legal. They supported the rights of free labor. Foner, pp. 142 & 143. Lincoln was elected with the solid support of the North, which gave him a strong victory in the Electoral College with no votes from the South. He wasn’t even on the ballot in some Southern states. Even the South’s advantage from the 3/5ths rule could not stem the tide of a solid North. If all of the votes of the three other candidates had been combined into one, Lincoln would have won in the Electoral College. Foner, p. 144.

Lincoln was a minority, President. However, there was a clear preference for maintaining the Union because both Bell and Douglas were Unionist candidates.

The Scorpion’s Sting – Why the South Seceded When Lincoln Was Elected

Important Facts:

Before 1860, many abolitionists had a plan for ending slavery without war. It included the following: respect the constitutional right of the slave states to determine for themselves whether to permit or prohibit slavery; prevent the expansion of slavery into any new territory, specifically, the new territories of the West; encircle the slave states with a cordon of free territory; repeal or water-down the fugitive slave law so that slaves who reached free territory could not be arrested and returned to their masters; make Washington, D.C., an enclave bordering Maryland and Virginia, free territory; and cooperate with Great Britain in suppressing the already illegal transatlantic slave trade. The hope and prediction of the abolitionists was that within a few decades of the application of their policies by the federal government, slavery would die out and the Southern states would abolish it of their own accord. Oaks pp. 1 — 50.

By 1860, there was a popular metaphor by which Americans, North and South, described this plan. The metaphor was based on the myth (or perhaps it’s true) that if a scorpion is completely surrounded by fire, it will eventually sting itself in its head and die. Ibid. p. 25. Thus, in the words of Sherrard Clemens, a Congressman from Virginia, the plan was “to encircle the slave States of this Union with free States as a cordon of fire, and that slavery, like a scorpion, would sting itself to death.” Congressional Globe, 36th Cong., 1st Sesess., p. 586 quoted by Oaks at pp. 23 & 24.

While there is no record of Lincoln himself mentioning the Scorpion’s Sting (so far as TWM as been able to determine), his positions as a moderate Republican would stop the spread of slavery and slowly degrade the institution. The election of 1860 saw the first time that the federal government was under the control of a political party whose policies aggressively, if peacefully, sought the end of slavery. The leaders of the Slave Power agreed with the abolitionists that the policies of the Scorpion’s Sting would sap slavery of at least some of its vitality. The Slave Power saw that with the policies of the Scorpion’s Sting in place, the North’s advantages in numbers and manufacturing power would only grow. So, 1860 was the best time to resist. And, due to the superior leadership of its generals, such as Robert E. Lee, and the difficulty that the North had in finding generals who could match Southern military leadership, the Slave Power almost pulled it off.

Why Most People in the North Supported the War — Was the U.S. the only surviving democracy in 1860?

Important Facts:

Most Northerners supported the war only for the purpose of preserving the Union. This was not just out of American patriotism, but to ensure “that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.” In 1860, most of Europe was in the hands of a resurgent aristocracy; the promise of the French Revolution had been blunted. Napoleon III had been elected “Emperor” by universal male suffrage but ruled France as a dictator without interference from other democratic institutions. While Britain had a Parliament, only men with substantial property could vote. This excluded six out every seven adult males and did not change for several decades. The U.S. was the world’s only major democracy, and if it could not hold itself together, the cause of democracy throughout the world would have been set back for generations, if not discredited entirely.

Abraham Lincoln referred to this in the Gettysburg Address when he said,

- Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

- Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. . . . It is . . . for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us . . . that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

From the beginning of the Civil War, the abolitionists fought to end slavery as well as to save the Union, but they were a minority. Foner, p. 163. It was only as the war progressed, with unbelievably high casualties and black troops making a significant contribution to the Northern War effort, that Lincoln and a majority in the North realized that the cancer of slavery had to be eradicated for the nation to come together and progress. In addition, the elimination of slavery was a reason for the war and the incredible carnage that was holy as preserving modern democracy. This became a commonly presented theme, expressed, for example, by Stevens in his January 5, 1865 speech on the House Floor supporting the 13th Amendment and by Lincoln in his Second Inaugural.

Actions Before January 31, 1865, Taken by Lincoln, Congress, the Army, and the Various States to Restrict or Eliminate Slavery

Important Facts:

- In August 1861, Congress passed the First Confiscation Act freeing slaves used for military purposes by the South and prohibiting the Army from returning captured or runaway slaves who had been used in the Confederate war effort. Lincoln signed the bill into law.

- In March 1862, Congress passed a law forbidding the Union armed forces from returning fugitive slaves. Lincoln signed the bill into law.

- On April 10, 1862 Congress pledged the federal government to pay for any slave freed by a slaveholder.

- On April 16, 1862 Congress freed the slaves in the District of Columbia and provided for compensation to loyal owners. Lincoln signed the bill into law.

- In June 1862, Congress adopted Thomas Jefferson’s proposal to prohibit slavery in the territories. This law repudiated the Dred Scott decision and Stephen A. Douglas’ popular sovereignty. Lincoln signed the bill into law.

- In July 1862, Congress passed the Second Confiscation Act freeing all slaves owned by masters who participated in the rebellion. Lincoln signed the bill into law.

- On January 1, 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation gave hope for freedom to the three to four million slaves still under Confederate control. It encouraged them to run away from their masters and to cross Union lines. The Emancipation Proclamation freed slaves in areas then in open rebellion, excluding slaveholding states that had stayed loyal to the Union: Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware. It did not include the state of Tennessee which was under Union control, the District of Columbia, the dissident counties of Virginia that would form the state of West Virginia, and those areas of New Orleans and its suburbs that were under Union control. As a practical matter, the Proclamation freed no more than 50,000 slaves, but as Union Armies advanced throughout the rest of the war, all the slaves they encountered were freed. Lincoln worked to increase the number of slaves crossing Union lines.

- Slaves who enlisted in the Union Army were promised, first freedom for themselves and later freedom for their wives and children; this policy greatly reduced the number of slaves in the border states, particularly in Kentucky.

- By the end of the war, the Army’s policy concerning contrabands, following the orders of the Congress and the President, had allowed approximately 400,000 slaves to cross Union lines to freedom.

- In February 1864, the Women’s National Loyal League, an organization of abolitionist feminists headed by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, submitted to Congress a petition containing 400,000 signatures seeking a Constitutional amendment abolishing slavery. On April 8, 1864, the Senate adopted a resolution proposing the 13th Amendment to the States. It was forwarded to the House of Representatives for concurrence, a necessary step in the Constitutional amendment process. However, on June 15 the House was unable to muster the 2/3rds majority to join the Senate. The 13th Amendment then languished until January of 1865.

- States, with Lincoln’s active encouragement, were banning slavery. These included, in early 1864: restored Union governments in Virginia and Arkansas; in August 1864, the border state of Maryland; in September 1964, restored governments in Tennessee and Louisiana, and on January 11, 1865 the border state of Missouri. On the eve of the vote on the 13th Amendment, if the Emancipation Proclamation was a valid exercise of Presidential power, slavery was legal only in Kentucky, with between 60,000 and 100,000 slaves, and in Delaware with less than 1,000 slaves. (Note that even in Kentucky slavery had been severely undermined because some 24,000 black Kentuckians had enlisted in the Union Army, securing freedom for themselves and their families.)

- By 1865, Lincoln had appointed a majority of the justices who sat on the Supreme Court. The new Chief Justice, Salmon P. Chase, had been Lincoln’s Secretary of the Treasury and was a committed abolitionist.

What actions did African-Americans, slave and free, take which set the stage for passage of the 13th Amendment?

Important Facts:

Here are some of the major actions taken by blacks that supported the cause of Emancipation:

1) About 179,000 men had enlisted in the Union Army and constituted about 10% of the entire Army. Another 19,000 black sailors served in the U.S. Navy. This was more than 1/5th of the adult black male population younger than 45. About 40,000 African-American soldiers died during the war, 30,000 from infection or disease. Foner, p. 252 & National Archives. While discrimination in the Northern Army often kept black soldiers from the battlefield, by January of 1865, black soldiers had fought bravely many times in some very hard fights. These men fought to end slavery.

2) 400,000 slaves had fled to Union lines and were classified as “contrabands.” They were initially housed in Union forts, but when their numbers became too great they were moved to Contraband camps. There were more than 100 of these camps by the end of the war. The contrabands were often employed as laborers by the Union Army and Navy. After 1863, the men were encouraged to enlist in the Union Army or Navy.

3) Free blacks in the North were active in the abolition movement.

What would all of these people have done if there had been a move to return them to slavery? The soldiers, still organized in their units would have revolted, the Contrabands would have rioted, and the free blacks in the North would have protested. A strong argument could be made that once blacks, about 200,000 strong, had served in the Union military, fought hard, and had been promised their freedom, and also once about 400,000 contrabands had crossed Union lines under a promise of freedom and lived freely for a time, the country could not go back on its promises and re-enslave them. Similar reasoning applied to the 3 to 4 million slaves in the South who had all heard about the Emancipation Proclamation and its promise of freedom. Moreover, the United States (that is white America) had a moral duty to keep its promises. This was an argument frequently used by Lincoln when he spoke or wrote to War Democrats and conservative Republicans.

Some War Democrats Changed their Position On the Amendment Out of Conviction – Including John Rollins, Samuel S. Cox, and Tammany Hall,

Important Facts:

Democratic politicians changed positions on slavery before the vote on the 13th Amendment. (Vorenberg pp. 203 & 204: “Without the change of heart of slavery’s former defenders, Congress would not have passed the amendment at this moment.”) It was changed in position by War Democrats, many of them concerned that continued opposition to slavery would mean electoral defeat for their party, that brought Lincoln and Seward to within striking distance of winning. They then used patronage to convince other lame duck Democratic Congressman to vote for the Amendment. John Rollins, who claimed to represent the strongest slave district in Missouri and who owned many slaves, changed his mind and voted for the Amendment. Lincoln recruited Samuel S. Cox of Ohio, a respected War Democrat, to lobby his colleagues in favor of the Amendment. Cox was credited with changing six votes for the measure but ended up voting against it himself because he came to believe that passing the amendment would scuttle peace negotiations and prolong the war. However, had his vote been crucial it is believed that he would have voted for the Amendment. Tammany Hall, for the good of the Democratic Party, switched its position and supported the Amendment, although some Representatives associated with it maintained their opposition.

At the end of this series of reports, teachers should note for the class the following:

- After January 1, 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation freed more and more slaves as the Union Army liberated ever greater swaths of Confederate territory. Even as the Amendment was being debated, Sherman’s army was advancing through the Carolinas and freed slaves were burning plantations. Some 400,000 contrabands had freed themselves by crossing Union lines. Congress had passed laws abolishing slavery in Washington D.C. and the territories in 1862 and 1863. Border states of Missouri and Maryland had emancipated their slaves. The 13th Amendment actually freed only the slaves in Kentucky, about 60,000–100,000, and the slaves in Delaware, less than 1000.

- For many, the purpose of the Amendment was to remove from the Constitution an important defect, i.e., the protections given to slavery, and prevent the possibility of another civil war by eliminating the one issue that the normal processes of the Constitution had been unable to resolve. Charles Francis Adams, U.S. Ambassador to Britain during the Civil War, son of President J.Q. Adams, and grandson of President John Adams wrote that the “class of slave owners with their old democratic allies of the north [may] . . . . attempt to re-establish the Union as it was [with a constitution that protected slavery]…. Not that I doubt the fact that in any event slavery is doomed. The only difference will be that in dying it may cause us another sharp convulsion, which we might avoid by finishing it now.” Vorenberg p. 59.

- The Amendment was less about granting freedom to people still enslaved than about making sure that the gains made in abolishing slavery could not be rolled back. The Amendment ensured that the Emancipation Proclamation would not be revoked or declared unconstitutional, and it eliminated the constitutional and legal framework for slavery throughout the country. It prevented more turmoil and perhaps another rebellion when the North would later seek to abolish slavery. Lincoln and the Republicans backed the 13th Amendment to protect anti-slavery gains, remove protections for slavery in the Constitution, and prevent civil strife in the future.

A few more reports:

Elizabeth Keckley — Entrepreneur, Modiste, and Confidante of Mary Lincoln

Important Facts:

Elizabeth Keckley was born into slavery in 1818. Mrs. Keckley was a mulatta and her son, George, had been fathered by a white man through a forced sexual encounter. Mrs. Keckley avoided having other children because they would have been slaves. She was a talented seamstress and an entrepreneur who for many years supported the family of her otherwise financially distressed owner. When she was living in St. Louis, Missouri, Mrs. Keckley demanded to be able to purchase her freedom. In 1855, some of her white customers advanced the $1200 required by her owner, and she paid them back with the earnings from her dressmaking business. She then moved to Washington, D.C. and served the wives of the city’s elite. She made dresses for Mrs. Jefferson Davis, whose husband served as a U.S. Senator and Secretary of War before Secession. She sewed for the wife of Robert E. Lee, at that time an officer in the U.S. Army. When Abraham Lincoln was elected president, Mrs. Lincoln hired Mrs. Keckley as her dressmaker. Mrs. Keckley soon became the First Lady’s confidante.

Mrs. Keckley’s son, George, passed as white and enlisted in the Union Army in 1861, two years before blacks were permitted to serve as Union soldiers. He was killed in action shortly after he enlisted.

Mrs. Keckley founded and headed the Contraband Relief Organization, a group of middle and upper class African-Americans and abolitionists who sought to improve conditions and provide education for the thousands of contrabands who flocked to Washington, D. C. during the war.

Seward and Lincoln

Important Facts:

When Lincoln was elected President, his only experience was serving in the Illinois Legislature and one term in the U.S. House of Representatives. Seward, who had been governor of New York and a U.S. Senator, was much more experienced than Lincoln. He had been Lincoln’s chief rival for the 1860 Republican Presidential nomination. When Lincoln asked him to be Secretary of State, Seward assumed that he could control the President. Soon Seward saw that Lincoln was a master politician and statesman. He came to respect and admire the President, serving him loyally. “The President is the best of us,” he wrote to his wife. Brodie p. 195. The two men became close friends, and Lincoln often walked the short distance from the White House to Seward’s elegant home for an evening of laughs, wine, and song.

The assassination of Abraham Lincoln was part of a conspiracy to kill several high government officials. On the night of the assassination, one of Booth’s co-conspirators invaded Seward’s home and seriously wounded the Secretary of State with a knife. He also stabbed Seward’s son when the younger Seward tried to stop the man from killing his father. Seward eventually recovered and served out his term as Secretary of State.