MARCH OF THE PENGUINS

SUBJECTS — Science; the Environment; World/Antarctica;

SOCIAL-EMOTIONAL LEARNING — Caring for Animals;

MORAL-ETHICAL EMPHASIS — None.

AGE; 10+; MPAA Rating — G;

Documentary; 2005; 85 minutes; Color.

There is NO AI content on this website. All content on TeachWithMovies.org has been written by human beings.

SUBJECTS — Science; the Environment; World/Antarctica;

SOCIAL-EMOTIONAL LEARNING — Caring for Animals;

MORAL-ETHICAL EMPHASIS — None.

AGE; 10+; MPAA Rating — G;

Documentary; 2005; 85 minutes; Color.

One of the Best! This movie is on TWM’s list of the best movies to supplement classes in Science, High School Level.

For a movie worksheet for this film, see Film Study Worksheet for a Documentary.

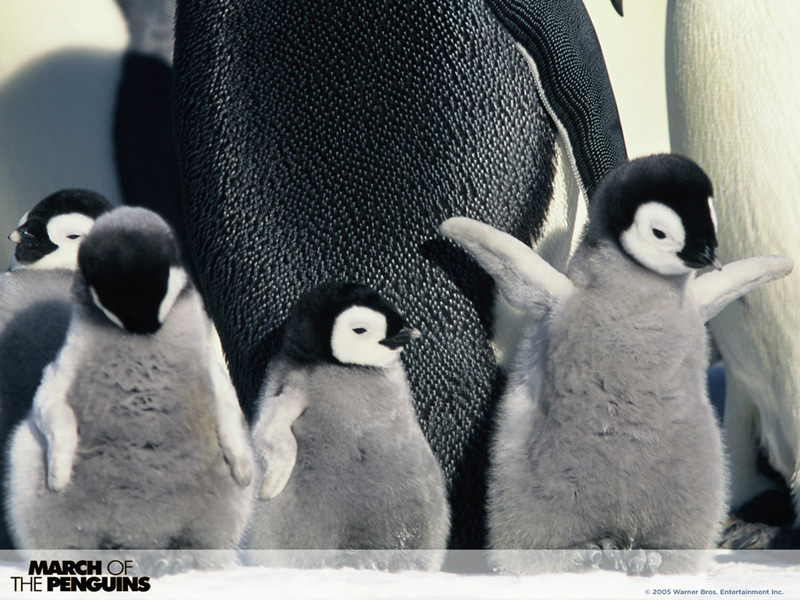

This film describes a year in the life of an Emperor penguin colony. The special features provide additional information concerning penguins, their environment, and the filming of the movie.

Selected Awards:

2006 Academy Awards: Best Documentary.

Featured Actors:

Narrator: Morgan Freeman.

Director:

Luc Jacquet.

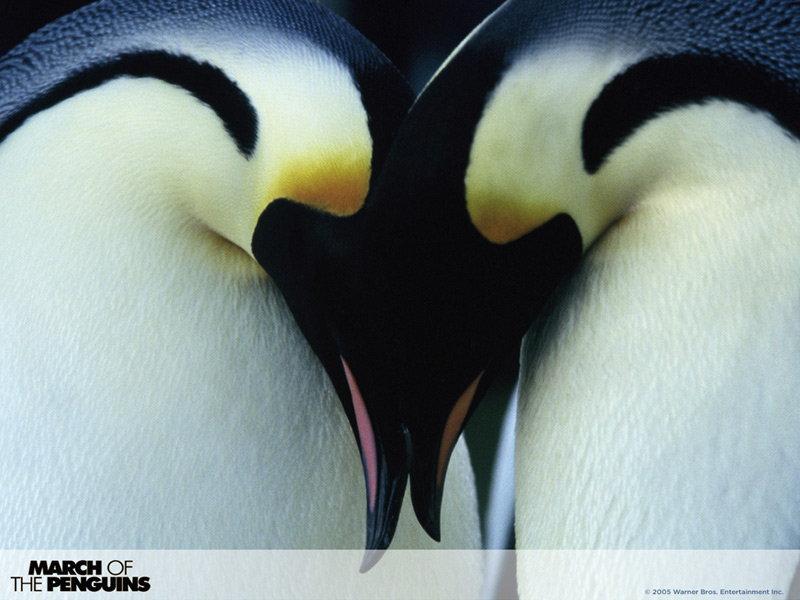

“March of the Penguins” shows how these beautiful birds have adapted to one of the most challenging environments on Earth. The film shows the amazing beauty and harshness of Antarctica. It is an excellent supplement to units on biology that deal with birds or the Antarctic.

None.

For all children ask, and help them to answer the Social-Emotional Learning Discussion Questions. For younger children add the Quick Discussion Question. For older children ask and help them answer Discussion Questions #s 2 and 3.

The movie is a documentary and provides its own factual background. A number of websites provide concise information about Emperor penguins. These include Creature Feature: Emperor Penguins by National Geographic; Animal Diversity Web article on the Emperor penguins; Antarctic Penguins by Guillaume Dargaud; and Emperor Penguins by Barbara Wienecke, Phd.

A number of themes run through the movie. If these are discussed with young viewers, the film can help to convey several basic concepts in biology.

Despite losses caused by the harsh environment and by predators, the Emperor penguin population is relatively stable. Only 19% of the chicks live beyond their first year. However, once they reach adulthood, 95% of the penguins survive from year to year. The average life expectancy of an adult Emperor penguin is 19 years. After the age of four or five, penguins start to lay eggs and reproduce. A rough calculation shows how these statistics are consistent with a relatively stable population: 14 (reproductive years) X .19 (survival rate for chicks to one year) X .5 (for two penguins required for one egg) = 1.33 chicks who reach adulthood per penguin. This number does not take into account lost and frozen eggs or chicks that die after the first year but before they begin to reproduce, so it is too high. That is probably the extra .33.

There are between 20 and 40 Emperor penguin colonies in Antarctica. As of 1995, the Emperor penguin population was estimated to be approximately 200,000 breeding pairs or a total population of about 400,000 – 450,000. There is no evidence that global climate change or human disturbance have substantially decreased their numbers.

Like many other animals (including human beings) the survival of the species depends on social interaction between parents and among parents and chicks. In March or April, Emperor penguins pair off for the breeding season. After each mother produces her egg she transfers it to its father. The mothers then immediately return to the sea to feed. The fathers survive the harsh arctic winter by huddling together to keep warm. The mothers don’t come back until the dead of winter. By then the chicks have just recently hatched. The mothers feed the chicks fish regurgitated from the mothers’ stomachs. The fathers, not having eaten anything for more than four months, then have their chance to return to the sea. Before they leave, the fathers memorize the distinctive call of their chick so that they can later locate their own. Like the fathers, the mothers protect themselves from the cold and storm by huddling together. When the fathers come back to the colony, they feed the chicks and the mothers return to the sea. The parents take turns baby-sitting their chicks on the pack ice and returning to the sea to fish through December or January (the height of the antarctic summer) when the chicks are large enough to fend for themselves. Any break in the chain (the death of a father or a mother, or a delayed return) will spell the end for the chick.

The survival of the colony also depends upon the social interactions among the group. The penguins march together from the sea to their breeding ground on the pack ice and back to the sea. The penguins huddle together against the cold, rotating positions to allow each to spend some time in the warmer interior of the group. They use their numbers to confuse predators such as the sea lion.

It is sometimes difficult to remember when watching these animals that they are flightless birds with feathers instead of fur. Their actions seem distinctly mammalian.

Emperor penguins are an important part of the antarctic ecology. They eat fish, crustaceans, octopi, and squid. In turn they serve as significant food sources for their predators, Leopard Seals, Orca whales, Antarctic Giant Petrels and Antarctic Skuas (another bird).

The taxonomy of the Emperor penguin is: Kingdom: Animalia; Phylum: Chordata (animals with spinal cords); Subphylum: Vertebrata (animals with spinal chords encased in vertebrae); Class: Aves (birds); Order: Sphenisciformes (penguins); Family: Spheniscidae (penguins); Genus: Aptenodytes (Emperor penguin and King penguin); Species: Aptenodytes forsteri (Emperor penguins).

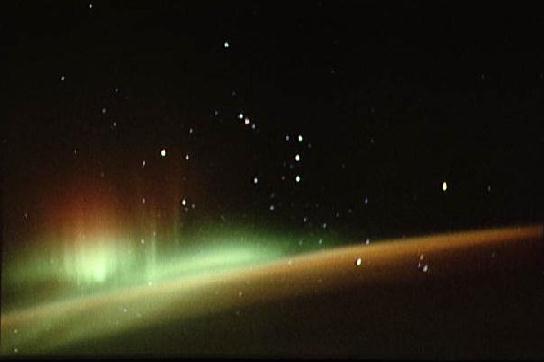

Southern Lights — Photo from NASA

The caption from this photograph by NASA states: “Looking toward the south from low Earth orbit, the crew of the Space Shuttle Endeavor made this stunning time exposure of the Aurora Australis or southern lights in April of 1994. Aurora is visible at high northern latitudes as well, with the northern lights known as Aurora Borealis. They are caused by high energy electrons from the Solar Wind which are funneled into the atmosphere near the poles by the Earth’s magnetic field. The reddish colors occur at the highest altitudes (about 200 miles) where the air is least dense. At lower altitudes and greater densities, green tends to dominate ranging to a pinkish glow at the lowest. The familiar constellation of Orion the Hunter is clearly visible above the dark horizon in the background. Because of the shuttle’s orbital motion, the bright stars in Orion appear slightly elongated.”

See also the Aurora Page from Michigan Tech.

1. See Standard Discussion Questions Suitable for Any Film.

No Suggested Responses.

2. How do social interactions benefit Emperor Penguins?

Suggested Response:

See the Helpful Background Section.

3. How do Emperor Penguin colonies survive with such a substantial loss of chicks and adults when each couple has only one egg each year?

Suggested Response:

The life span of the average Emperor Penguin adult is about 19 years. They can breed for 14 or 15 years. 19% of chicks survive beyond the first year. A rough calculation shows how these statistics are consistent with a relatively stable population: 14 (reproductive years) X .19 (survival rate for chicks to one year) X .5 (for two penguins required for one egg) = 1.33 chicks who reach adulthood per penguin. This number does not take into account lost and frozen eggs or chicks that die after the first year but before they begin to reproduce, so it is too high. That is probably the extra .33.

4. In the summer, Emperor Penguins live and feed in Antarctic ocean waters. In the Antarctic fall, March, and April, they go onto the pack ice to pair up and to breed. The mother lays the egg which the father (still at the breeding ground on the pack ice) incubates in a special insulated pouch. This takes most of the arctic winter. Penguins eat fish and other animals found in the ocean. There is no food for them on the pack ice. After the mother lays the egg, she returns to the ocean to feed. When the egg hatches the mother travels back over the pack ice to feed the chick with food regurgitated from her stomach. By that time, the father will have been without food for about four months. The mother then takes responsibility for the chick while the starving father returns to the sea. He comes back to the breeding ground with a stomach full of food for the chick. The parents then take turns going back and forth with one babysitting and feeding the chick on the pack ice while the other goes to the ocean to get food for him or herself and the chick. This continues until the summer (December or January) when the chick is old enough to fend for itself. Certainly, the ocean and the pack ice are different biomes. Do Emperor Penguins engage in classic biome migration? (For a shorter version, just ask the question: Do Emperor Penguins engage in classic biome migration?)

Suggested Response:

No. Emperor Penguins do not breed and hatch their eggs during the spring and summer in which they take advantage of the food provided by the explosion of life that occurs when temperatures in cold climates become warmer. They reproduce in the fall and winter in some of the harshest conditions on earth. For a description of classic biome migration, see, generally, Lesson Plan on Migration, Nomadism, and Dormancy.

1. How can we best show our respect for Emperor Penguins?

Suggested Response:

Leave them alone and make sure that our actions impact their habitat as little as possible.

2. What would be lost if a species such as the Emperor Penguin became extinct?

Suggested Response:

A unique and beautiful part of creation and an important part of the Antarctic ecosystem would be lost forever. Emperor Penguins eat fish, crustaceans, octopi and squid. They are eaten by larger animals such as Leopard Seals and Orca whales. Chicks are also eaten by predatory birds.

1. See Assignments, Projects, and Activities for Use With Any Film that is a Work of Fiction.

2. Students can be asked to create a poster board display of the life cycle of the Emperor penguin.

See the websites set out in the Helpful Background Section and

The movie itself and the websites linked in the Guide.

This Learning Guide was last updated on December 16, 2009.

How do Emperor penguins keep warm?

Suggested Response:

There are three ways. (1) Their feathers are designed to trap air and insulate them from the cold. (2) They have a lot of body fat. (3) They huddle together in large groups.

* we respect your privacy. no spam here!