Below are excerpts from the January 15, 1965 telephone conversation between LBJ and Dr. King.

Note that the 1964 Civil Rights Act referred to by the President in this conversation forbids discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin in the workplace, schools, and facilities open to the general public. It is the landmark Civil Rights Legislation of the 1960s.

President Johnson: . . . I think that you can contribute a great deal by getting your leaders and you, yourself, taking very simple examples of discrimination where a man’s got to memorize [Henry Wadsworth] Longfellow, or whether he’s got to quote the first ten amendments, or he’s got to tell you what Amendment 15 and 16 and 17 is, and then ask them if they know and show what happens, and some people don’t have to do that, but when a Negro comes in, he’s got to do it. And if we can just repeat and repeat and repeat—I don’t want to follow [Adolf] Hitler, but he had an idea—

King: Yeah.

President Johnson: —that if you just take a simple thing and repeat it often enough, even if it wasn’t true, why, people’d accept it. Well, now, this is true, and if you can find the worst condition that you run into in Alabama, Mississippi, or Louisiana, or South Carolina where—well, I think one the worst I ever heard of is the president of the school at Tuskegee [Institute], or the head of the Government Department there, or something, being denied the right to cast a vote, and if you just take that one illustration and get it on radio, and get it on television, and get it on . . . in the pulpits, and get it in the meetings, get it every place you can, pretty soon the fellow that didn’t do anything but follow—drive a tractor, he’ll say, “Well, that’s not right, that’s not fair.”

King: Yes.

President Johnson: And then that will help us on what we’re going to shove through in the end.

King: Yes. You’re exactly right about that.

President Johnson: And if we do that, we’ll break through as—it’ll be the greatest breakthrough of anything, not even excepting this ’64 act, I think the greatest achievement of my administration. I think the greatest achievement in foreign policy—I said to a group yesterday—was the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

But I think this’ll be bigger, because it’ll do things that even that ’64 Act couldn’t do. . . . [End of Conversation]

Analysis of the Movie Selma as a Work of Historical Fiction

The genre of historical fiction presents events from the past in a fictional format. Most Americans get their post-schooling history from movies that are works of historical fiction. Responsible directors trying to present a reasonably accurate view of historical events will sometimes change specific facts or the sequence of events to make their stories more interesting or to simplify complex situations. So long as the important historical facts are retained, these changes are legitimate poetic license. Unfortunately, some directors distort the historical record out of ignorance or to support their own agenda.

The director of Selma who also wrote some of the script claims to be a student of the history of the period covered by the movie. In addition, the producers of Selma are distributing it free to high schools through the “Selma for Students’ Initiative,” claiming that the movie is responsible for historical fiction suitable to being shown to students.

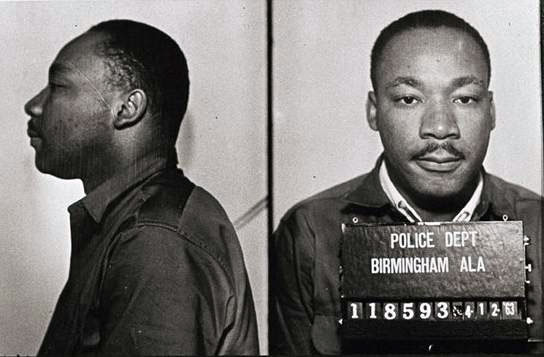

TWM’s research, including both primary and secondary sources, shows that the presentation of the events of the protests, the portrayal of Dr. King and other leaders of the Civil Rights movement, and the description of the resistance they met in Alabama, are all reasonably accurate and beneficial. Actor David Oyelowo’s portrayal of Dr. King is excellent. [This reviewer had the privilege of attending a speech given by Dr. King in Tallahassee, Florida, a few weeks after the bombing in Birmingham that killed the four little girls. In those days, whites attending civil rights protests or meetings were always placed in the front rows to increase their visibility, so Dr. King was only about 15 feet away. This reviewer could observe him closely,y and even now, some 50 years later, the event is clear in his mind.]

However, as discussed in the section or the Learning Guide entitled President Lyndon Baines Johnson, a Hero of the Civil Rights Movement, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, only a few of the scenes in the film in which LBJ appears are reasonably accurate, and some show the opposite of what actually occurred. In fact, contrary to the impression left by the film, LBJ was committed to passing a voting rights law in 1965; he and Dr. King worked together to get the law passed; LBJ’s role was one of the indispensable parts of that effort.

Thus, in its description of the role of President Lyndon Johnson, the general historical accuracy of the film falls prey to director/screen writer Ava Duvernay’s desire for a clear villain and her insistence that, “I wasn’t interested in making a white-savior movie.”

What’s Right with Showing How Much LBJ Did for Black Americans?

It’s a sad irony that LBJ is depicted as resisting civil rights for African Americans in a movie that sells itself as a reasonably accurate portrayal of a pivotal event in the struggle for equal rights. The suppression of LBJ’s advocacy of civil rights also misses an opportunity to show power of nonviolent direct action to motivate leaders to do the right thing. However, the most regrettable fact about director/screenwriter Duvernay’s false depiction of LBJ as the Southern White antagonist of Dr. King and an opponent of reform, is that the film misses an opportunity to promote social cohesion in the U.S.

Cohesion in multi-ethnic, multi-racial societies is always difficult to achieve. It is easy to divide people from others and to motivate them with anger. One of the great glories of the U.S. is our ability to resist the challenges of those who seek to divide one group from another and our capacity to achieve social cohesion in a society of many races, ethnicities, and religions. Thus, the occasions when people come together to do the right thing are important to emphasize. Many white Americans have much to answer for in their treatment of African Americans. However, there have been occasions when whites did the right thing. Good conduct should be encouraged and actions which foster cohesion in society should be celebrated; this is a major component of nonviolent direct action. LBJ’s actions on civil rights after 1957, and especially during his Presidency, are a series of wonderful right actions, one after another, and American history students should know about what he did. Certainly, he should not be misrepresented as resisting the Civil Rights Movement while he was President.

Why Director/Screenwriter Ava Duvernay Wanted to Suppress LBJ’s Role in the Civil Rights Movement

Ava Duvernay, the first black female director to make a successful feature motion picture, explained her position on the controversy over the way LBJ is treated in the movie in an interview for the January 5, 2015, edition of Rolling Stone Magazine.

Rolling Stone: Let’s talk about reducing LBJ’s role in the events you depict in the film.

DuVernay: Every filmmaker imbues a movie with their own point of view. The [draft of the script received from screen writer Paul Webb] was the LBJ/King thing, but originally, it was much more slanted to Johnson. I wasn’t interested in making a white-savior movie; I was interested in making a movie centered on the people of Selma. . . .

This is a dramatization of the events. But what’s important for me as a student of this time in history is to not deify what the president did. Johnson has been hailed as a hero of that time, and he was, but we’re talking about a reluctant hero. He was cajoled and pushed, he was protective of a legacy — he was not doing things out of the goodness of his heart. Does it make it any worse or any better? I don’t think so. History is history and he did do it eventually. But there was some process to it that was important to show.

Rolling Stone: Many presidents couldn’t have done it.

DuVernay: Absolutely. Or wouldn’t have even if they could.

This sounds like the director came to the film with an agenda and that she imposed that agenda on the actual facts by declining to acknowledge President Johnson’s role as “a hero of that time.”

There are some arguments supporting the director. It was not until 1957, seven years before the Selma march, that LBJ first supported legislation protecting civil rights for African Americans. Thus, the movie’s timeline for LBJ’s conversion from an opponent of civil rights legislation to the politician who did more for black civil rights than any other 20th-century white leader is only about eight years off. Writers of historical fiction often telescope timelines to show important facts of history; this is a legitimate technique of writing historical fiction.

In addition, one of the traditional failings of Hollywood films in showing the history of black America is that the movies focus on white heroes helping blacks, ignoring the fact that the Civil Rights Movement was led by African Americans and its victories were won by mostly black demonstrators, with whites playing a relatively minor, but still helpful role. Movies about the Civil Rights Movement that focus on whites include The Help and The Long Walk Home. Even films about the important contributions of free blacks and former slaves in winning the Civil War have focused on whites, see e.g., Glory. The reasons for this are not necessarily racism. The vast majority of the movie-going audience is white. Those audiences will more readily identify with white heroes. Moviemakers want to sell tickets and thus want to appeal to the broadest possible audience. Director Duvernay’s statement that she “wasn’t interested in making a white-savior movie” is a reference to those films.

However, there were plenty of villains in the story told by this movie, including George Wallace, J. Edgar Hoover, Sheriff Jim Clark, and the reluctant Congress. In addition, LBJ could have been made out to be less of a villain simply by excluding made-up scenes and by showing how he came to be an advocate for civil rights. Especially egregious is the false scene with J. Edgar Hoover in which the LBJ-character gives tacit approval to an effort to undermine Dr. King’s family. There is simply no evidence that President Johnson was aware of the poison pen letter and the tape.

In addition, it would not have been difficult, for example, to insert a scene or two that told the story of Johnson’s pre-1957 opposition to civil rights laws, about his change of position as a result of nonviolent direct action, and his leadership on civil rights when he was President.

As the movie stands, Selma will leave the millions of Americans who watch the movie with a serious misimpression that divides rather than unites. In that sense, it is not good historical fiction and should only be shown in classes if teachers correct for the misimpression that LBJ as President resisted moving forward on civil rights in general and on the 1965 Voting Rights Act in particular.