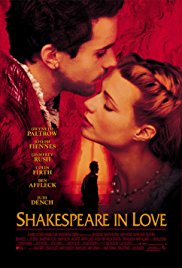

SHAKESPEARE IN LOVE

AN INTRODUCTION TO ROMEO AND JULIET

Subject: Drama/England: Romeo and Juliet

Ages: 14+

Length: Clip: 40 minutes; Lesson: One and one-half to two 45 – 50 minute class periods.

There is NO AI content on this website. All content on TeachWithMovies.org has been written by human beings.

AN INTRODUCTION TO ROMEO AND JULIET

Subject: Drama/England: Romeo and Juliet

Ages: 14+

Length: Clip: 40 minutes; Lesson: One and one-half to two 45 – 50 minute class periods.

Using the Snippet in Class:

Students will be primed to read Romeo and Juliet. The film clip and the introductory lecture will introduce them to Elizabethan theater and to the London of Shakespeare’s time.

When students feel that they know an author as a person, they will be more interested in reading what he or she has written. An introduction to the times in which a play was first performed is helpful in appreciating the artistry and meaning of the work.

“Shakespeare in Love” presents students with a brilliantly re-imagined world of the Elizabethan stage and Shakespeare’s London. The movie presents an entertaining and accessible speculation about how the playwright could have labored over his words and conceits and, out of his own lost love, found the inspiration for Romeo and Juliet. Tom Stoppard’s script cleverly mixes modern allusions, historical characters and events, passages from the play, borrowings from Christopher Marlowe, and visual puns. Students will be able to trace the parallels between the doomed love of Romeo and Juliet, and the impossible love of Will and Viola. Students will get a good sense of Elizabethan stagecraft.

The first 40 minutes of the movie are enough to provide most of the benefits of the film. This snippet does not include the scenes which earned the movie its R rating. The snippet would probably be rated PG-13.

1. Review the clip and to make sure it is suitable for the class. Note any words that the class may not understand and use them in vocabulary exercises before showing the movie. Review the Lesson Plan and decide how to present it to the class, making any necessary modifications.

2. The film clip starts at the beginning of the movie. Cue the DVD to start after the coming attractions and the studio logos. Make sure that all necessary materials are available.

1. Vocabulary

Teach the class any vocabulary words necessary to appreciate the film. TWM suggests that the vocabulary include the following: groundling, prose, quil, rank, wordwright, chamber pot, and anon.

2. Introductory lecture

Introduce the film with direct instruction that includes the following points:

An individual’s will, talent, and personality (primarily white male individuals), not just his social position at birth, could affect the arc of his life. Shakespeare himself is an example of a man who, through talent and hard work, rose from modest beginnings to the top of the artistic world. This was also seen in some of the characters that populate Shakespeare’s plays. One of his famous tragic heroes was a dark-skinned Moor who was able to transcend his race and origins to become a high ranking general in the Venetian military and to marry a white woman, the beautiful Desdemona.

(Graphic representations of social mobility can be helpful to show the inability to change one’s social position in the Middle Ages and the ability the move among vocations and to better oneself in the Renaissance.)

South London at the close of the 16th century was a rough and rollicking area of brothels, bars, and the Rose Theater, which was home to many of Shakespeare’s and Marlowe’s productions. Actors were considered to be low-life characters with little social standing.

(Show the locations of the River Thames, South London, and The Rose. There are great models and images of The Rose on the Internet. Even a rough sketch on the blackboard will serve to give students a sense of the physical location of the two theaters.)

Outbreaks of the Plague resulted in the closing of the theaters for extended periods. But people from all walks of life, from illiterate groundlings to Queen Elizabeth, loved to watch plays. Shakespeare had to interest the whole range of these patrons from the outset of each play. Thus, his scripts contain elevated speech-making and witty wordplay, but also dirty puns and a rising threat of violence to come. [Ask students to look for this when they begin to read Romeo and Juliet and to think of the first five minutes of the last movie they saw. What are the hooks in the play? What was the hook in the movie?]

The view of Shakespeare’s life and character presented in the film is not shared by all who have studied his life and times. Some scholars claim that Shakespeare was a pen name for the Earl of Essex, who could not write under his own name because writing plays was considered beneath the dignity of the nobility. One proponent of this view cites evidence of an early frustrated romance that could have inspired the Earl to write Romeo and Juliet.

3. The “Shakespeare in Love Worksheet“

Before showing the film hand out the Shakespeare in Love Worksheet. Read over the questions with the class and tell students they can jot down notes on the answers while watching the movie. Tell the class that after the snippet is completed, they will be required to write full answers to the questions, using the information from both the movie and the lecture. They will be able to use their notes to assist in answering the questions. This assignment will lead students to pay close attention to the film.

4. Watch the First 40 Minutes of the Movie

Be sure to stop the film before Will finishes unwrapping Viola.

5. Exercises at the End of the Film

Have the class perform an exercise with the Shakespeare in Love Worksheet. For example, after the snippet, divide the students into two or more teams. Team #1 gets first crack at question # 1. If they can’t answer, Team #2 gets a chance. Team #2 has the first opportunity to answer question #2, and so on until the worksheet is completed. Then allow the students to fill in the responses to the worksheet. Another alternative is to have the students fill out the worksheets before or after a class discussion relating to the responses. Collect each individual worksheet for credit.

6. Begin the Lesson on Romeo & Juliet.

The class will now be primed to begin their study of Romeo and Julilet. The TWM Learning Guide to the movie contains ideas to include in your lesson plan for the play.

See also, DiMatteo, Anthony, The Use and Abuse of Shakespeare: A Review Essay College Literature – 31.2, Spring 2004, pp. 185-195 and Greenblatt, Stephen, Renaissance Self-Fashioning: from More to Shakespeare, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ©2005.

This Snippet Lesson Plan was written by Deborah Elliott and James Frieden.

It was published August 20, 2010, and revised on March 16, 2011.