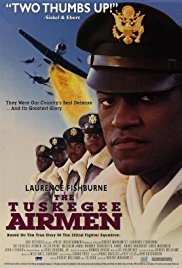

The Tuskegee Airmen shows another step on the road to full equality for African-Americans in the U.S. military. This long march began during the American Revolution when a few blacks fought for independence. During the Civil War, black foot soldiers gained the respect of the nation and demonstrated that blacks could fight under the conditions of modern warfare. (See Learning Guide to “Glory”.) Black regiments had made a substantial contribution to the Union war effort.

The Tuskegee Airmen proved that African-Americans could excel at the controls of complex fighter-bombers. General Benjamin O. Davis and other black officers during and after the Second World War demonstrated that blacks could successfully lead large military units. In 1948 President Truman ordered the complete integration of the armed forces. In 1989 General Colin Powell was selected by President George Bush to be the first African-American Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the highest military post in the United States.

The Tuskegee Airmen were the elite, African-American 99th Fighter Squadron (later expanded to the 332nd Fighter Group) commanded by Colonel Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. The Tuskegee Airmen flew more than 700 missions and were the only Fighter Group that never lost a bomber to enemy aircraft. They earned three unit citations, more than 744 Air Medals and Clusters, more than 100 Distinguished Flying Crosses, 14 Bronze Stars, 8 Purple Hearts, a Silver Star, and a Legion of Merit and the Red Star of Yugoslavia. The Tuskegee Airmen downed 111 enemy fighters, including three of the eight Messerschmitt ME-262 jets shot down by the Allies during the war. The 332nd also destroyed countless targets during ground attack missions and even sunk a German destroyer with machine gun fire that hit the ship’s ammunition stores triggering secondary explosions. Sixty-six Tuskegee Airmen (out of a total of 450 sent overseas) lost their lives in combat.

The pilots of the 332nd wanted to make sure that Allied bomber crews and enemy pilots could easily identify them. As a result they had the tails of their P-51 Mustangs painted red. When it became apparent that bombers escorted by the 332nd were going to be protected from enemy fighters, the bomber crews started calling them the “Red Tail Angels”.

The support personnel for the 332nd was comprised of black mechanics, medical technicians, administrative support and cooks. There were ten support personnel for every pilot.

In WWII, American pilots were not expected to fly more than approximately 50 missions before returning home. But due to “lack of replacements” the pilots of the 332nd Fighter Group flew closer to 100 missions, doubling the chance of injury and death. If they were fortunate enough to return home, men who had served in the most successful fighter squadron fielded by the United States found themselves shuttled back into “Colored Only” lines and denied access to “White Only” facilities.

The Army Air Corps favored daylight bombing in which targets on the ground could be hit with precision. The RAF (Royal Air Force) preferred nighttime bombing because, while much less precise, the bombers were safer from enemy attack. Fighter escorts were essential to protect the planes conducting a daylight bombing campaign. Before the fighter escorts were available, losses to bombers were unacceptably high and the daylight bombing campaign had to be suspended. See Learning Guide to “Twelve O’Clock High”.

Throughout the Second World War, the black community in the United States clamored for an opportunity to make a full contribution to the war effort. Before the war and during the early part of the war, the Navy restricted black sailors to the role of messmen, menial laborers, and servants for officers. During WWII black sailors sought the right to advance to other jobs, including combat positions. Black soldiers in the army asked to fight and to fly airplanes, rather than serve in simply support roles.

Despite the fact that black pilots had been flying planes for decades, many in the Army, the government, and much of the public didn’t think blacks could become competent pilots. The fight for black pilots in the military was led by newspapers serving the black community and organizations such as the NAACP. There was at least one law suit by a soldier seeking to be an army pilot. Eleanor Roosevelt, First Lady of the United States, played a pivotal role in helping the 99th to get airborne.

Because President Roosevelt was paralyzed, he had trained Mrs. Roosevelt to conduct fact finding missions on his behalf and to report her findings back to him. Mrs. Roosevelt was also a political power in her own right. She wrote a popular daily newspaper column and did not hesitate to bring political pressure to bear on government officials on issues that were important to her. Eleanor Roosevelt was the first leading white public figure who actively supported the aspirations of black Americans. Repeatedly throughout the war, and despite vilification heaped on her by racists, Mrs. Roosevelt pushed for better jobs and improved treatment for blacks in the defense industry and in the military. The Tuskegee Airmen were one focus of her efforts.

Mrs. Roosevelt knew how to muster public opinion. Her actions indicate that she set out to change the perception that blacks couldn’t fly planes and to overcome resistance by those in the Army and the government who didn’t want blacks to be military pilots. The official purpose of Mrs. Roosevelt’s visit to the Tuskegee airfield was to evaluate the potential of Tuskegee’s facilities and to meet black flyers. She arrived at the Tuskegee airstrip with an entourage of Secret Service men and at least one photographer. During the course of her visit, Mrs. Roosevelt asked Chief Anderson, a black flight instructor and an experienced pilot, “Can Negroes really fly airplanes?” His reply was, “Certainly we can; as a matter of fact, would you like to take an airplane ride?” Mrs. Roosevelt accepted. The Secret Service men forbade her to fly. Mrs. Roosevelt overruled them and proceeded toward the aircraft. The Secret Service men rushed into a nearby office and called President Roosevelt. After hearing the details of the situation, the President replied, “Well, if she wants to do it, there’s nothing we can do to stop her.”

With Mrs. Roosevelt in the back seat of his Piper J-3 Cub, Chief Anderson took a half-hour ride above the Alabama countryside. Upon landing, Mrs. Roosevelt turned to the Chief and said, “I guess Negroes can fly.” An historic photo was taken and was widely publicized. The photograph and Mrs. Roosevelt’s willingness to trust her life to a black pilot, went a long way toward convincing the public that blacks could safely fly military airplanes. This incident gave the program to train black fighter pilots a tremendous boost.

Eleanor Roosevelt did not limit herself to publicity in her efforts to get the 99th into combat. In March of 1943, Frederick Patterson, longtime President of Tuskegee Institute, wrote to her stating: “The program of preflight training is going forward but morale is disturbed by the fact that the 99th Pursuit Squadron trained for more than a year is still at Tuskegee and virtually idle.” On April 10 Mrs. Roosevelt sent a copy of Patterson’s letter to the Secretary of War with a cover note stating: “This seems to me a really crucial situation.” Five days later, on April 15, the Tuskegee Airmen boarded a ship bound for North Africa. The airmen and the black community were jubilant. (We don’t know if there was a cause and effect relationship between Eleanor Roosevelt’s letter and the troops getting on the ships. We do know that Franklin Roosevelt generally shared his wife’s desires to see improved job opportunities and treatment for black Americans and that he often worked through her on controversial issues. Other preliminary steps were being taken by the War Department at this time to end racial segregation. For example, on March 1, 1943, the War Department forbade designation of recreational facilities for particular races. We can’t believe that Secretary of War Stimson would have taken important steps on a sensitive issue, such as putting the black pilots on ships bound for North Africa, without checking with his boss.) No Ordinary Time by Doris Kearns Goodwin, 1994, Simon & Schuster, New York, see e.g., pp. 246 – 253 and 421 – 424 as to Mrs. Roosevelt’s efforts on behalf of blacks in defense industries and in the military, pp. 423 & 424 relate specifically to ER’s letter to the Secretary of War. For more information on Eleanor Roosevelt, see Learning Guide to Eleanor Roosevelt — The American Experience.

Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. was the first black American to become a General in the United States Air Force. His father had been the first black Brigadier General in the U.S. Army. When Davis attended West Point he was “silenced” for the four years until graduation, i.e., his fellow cadets would not talk to him because he was black. Despite this treatment, Davis graduated 35th in his class of 276 cadets and was commissioned a second lieutenant in 1936. When he graduated he requested Air Corps pilot training but was turned down. When the 99th Fighter Squadron was being trained at Tuskegee, Davis’ request was granted. He trained with the men and was placed in command of the squadron when it was deployed.

Comment on Historical Accuracy: The film is accurate as to the war record, and the competence and bravery of the 332nd Fighter Group. It portrays the difficulties that the airmen faced in overcoming the misperception that blacks could not handle fighter planes.

Events recounted in the film have strong parallels to what actually occurred. Examples not discussed above are:

There was a report circulating in the military that asserted that the black pilots “lacked discipline and motivation in the air.” This report, called “the Momyer Report,” was based on false and misleading descriptions of the record of the black fighter pilots. It was endorsed by the Commander of the Army Air Corps and reached the desk of the Assistant Secretary of War. It was also leaked to the press and resulted in an inaccurate and damaging story appearing in Time magazine. Benjamin Davis, Jr., at that time a Lieutenant Colonel, had to take vigorous action to counteract it. He was called to testify before a committee established by the War Department to evaluate the performance of black soldiers. We are not aware of whether the controversy reached the U.S. Senate or if there were disputes on the Senatorial level over the fate of the 99th Fighter Squadron, but certainly this occurred within the Army. One of the incidents in the report, mischaracterized as demonstrating cowardice by a black fighter pilot, is shown in the film when Roberts breaks formation to go after a German fighter. Black Knights, pp. 101 – 105.

An incident did occur in which the black pilots came to a briefing at the appointed time only to find that the briefing was ending. The time had been changed without notice to them. This occurred at Colonel Momyer’s headquarters during the Sicilian Campaign. Black Knights, p. 104.

The 99th did sink a destroyer by strafing it and hitting the ammunition stores.

This film shows how movies can be true to the spirit of the times and the historical events but, for the purpose of telling a story, use fictional characters to represent types of people. The melding of actual and representative characters is a traditional and legitimate device of historical fiction. It has been used in novels and plays, as well as movies. Other than Mrs. Roosevelt and General Benjamin O. Davis, the characters in “The Tuskegee Airmen” are fictional. However, most characters in the film represent various types of people who affected the lives of the flyers of the 332nd Fighter Group. The character named Colonel Noel Rogers, the base commander, stands for those in the military and society who wanted blacks to succeed and to become fighter pilots. (His closest real-life counterpart was Colonel Noel F. Parrish, the third Commander of Tuskegee Army Air Field who did much to make the dreams of the black flyers come true. The identical first name of the character and his real life counterpart is no coincidence. Other base commanders were not as supportive of the black cadets.) The character of Major Joy stands for those in the military who didn’t want to see the experiment succeed. The character of the experienced black fighter pilot who provided training in fighter tactics represents the black trainers who supported the cadets. The character of the bomber pilot captain from Texas represents the members of the armed forces who grew out of their racist attitudes toward blacks when the Tuskegee Airmen began saving their lives on a regular basis. The bomber co-pilot from California depicts the white members of the armed services who were willing to accept the black pilots without resistance. The characters of the cadets represent the men who had the courage to try to buck Jim Crow attitudes and laws and become the first black fighter pilots. The Senators stand for the many people in the government who were either opposing or supporting the project.

There are references in the film to sports figures Joe Louis, Max Schmeling, and Jesse Owens. Joe Louis, called “the Brown Bomber,” was the first great black heavyweight boxing champion. He defended his title 25 times and was beaten only three times. One of those losses was in 1936 to a German national named Max Schmeling. The Nazis sought to use Schmeling’s victory as proof of their “Aryan” racial superiority. In a 1938 rematch, Louis destroyed Schmeling in one round and Americans, white and black, celebrated the victory as a triumph for democracy. Louis was, of course, a special hero of black Americans. During the Second World War, Joe Louis served in the Army helping with recruiting and giving inspirational speeches.

Despite the fact that the Nazis sought to use Schmeling as a poster boy, Schmeling himself was no Nazi. He actually hid two Jewish boys in his hotel suite on Kristallnacht and later helped spirit them out of Germany. He served as a paratrooper in the German Army during the war but engaged in no atrocities. Schmeling boxed professionally after the war and used his earnings to purchase a Coca-Cola bottling plant. As a successful businessman, Schmeling became a leading philanthropist. See e.g., Max Schmeling: The Story of A Hero. Decades later, when Louis was in financial trouble, Schmeling was one of many people who sent him money.

Jesse Owens was a great black American athlete. He won four Gold Medals in the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games, spoiling Hitler’s plans to use the event to demonstrate the superiority of “Aryan” athletes. See Jesse Owens: The Official Website.

The film is inaccurate in its portrayal of the training process as essentially adversarial. The training pilots were mostly experienced, black pilots. The training process was rigorous and the “wash out” rate for black cadets was higher than that for white cadets. However, the Tuskegee Airmen reported that almost all the trainers were supportive. In addition, Mrs. Roosevelt did not fly with a cadet, rather she went up with an experienced flyer who trained the cadets. Her action was still courageous and important to the success of the program.