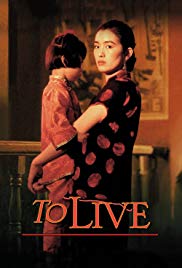

TO LIVE

(In Chinese with English Subtitles)

SUBJECTS — World/China;

SOCIAL-EMOTIONAL LEARNING — Surviving; Grieving; Gambling Addiction;

MORAL-ETHICAL EMPHASIS — Fairness.

AGE: 14+; No MPAA Rating;

Drama; 1994; 125 minutes; Color.

There is NO AI content on this website. All content on TeachWithMovies.org has been written by human beings.

(In Chinese with English Subtitles)

SUBJECTS — World/China;

SOCIAL-EMOTIONAL LEARNING — Surviving; Grieving; Gambling Addiction;

MORAL-ETHICAL EMPHASIS — Fairness.

AGE: 14+; No MPAA Rating;

Drama; 1994; 125 minutes; Color.

TWM offers the following worksheets to keep students’ minds on the movie and direct them to the lessons that can be learned from the film.

Film Study Worksheet for Social Studies Classes for a Work of Historical Fiction and

Worksheet for Cinematic and Theatrical Elements and Their Effects.

Teachers can modify the movie worksheets to fit the needs of each class. See also TWM’s Historical Fiction in Film Cross-Curricular Homework Project.

This film details the life of a Chinese family from the 1940s through the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s. The movie is based on the novel, Lifetimes by Yu Hua.

Selected Awards:

1994 British Academy Awards: Best Foreign Film; 1994 Cannes Film Festival: Best Actor (You), Grand Jury Prize; 1995 Golden Globe Awards: Best Foreign Language Film.

Featured Actors:

Ge You, Gong Li, Niu Ben, Guo Tao, Jiang Wu.

Director:

Zhang Yimou.

“To Live” is a primer on the changes in China from the 1940s to the 1960s seen from the standpoint of ordinary Chinese citizens. It also exposes the evils and risks of gambling addiction. The film was banned in China and the government prohibited its director and star actor from further activity in the movie industry for two years.

MODERATE. The film, while banned in China, still suffers from the effort to get it past the Chinese government censors. Reports that we have received from American citizens born in China who returned home for visits during the period shown by this film are that the police state has made each person distrustful of others, including family members. There would be, they report to us, no conversations of any substantive matters because of this distrust. The film only hints at this.

There is some blood in this movie, but little violence. We briefly see the bloody corpse of the couple’s son after he has been run over by a car. We are shown the blood from the daughter’s hemorrhage on the hospital bed clothes but do not see the daughter in these scenes. These scenes help convey the message of the film.

Review the recent history of China for your child. See the Helpful Background section. Ask and help your child to answer the Quick Discussion Question. If your child has an analytical mind and is interested in history, ask and discuss discussion question #4.

Mao Zedong (1893 – 1976) became the leader of the Chinese Communist Party in 1942 and ruler of China from 1949 until his death. Mao was the subject of enormous veneration by the Chinese people, becoming a godlike figure. Chinese citizens were required to read and reread “Quotations of Chairman Mao” (called Mao’s Little Red Book). His writings were treated as infallible. His philosophy (called “Mao Zedong Thought”) was raised to the level of a religion.

Mao maintained his power in the same manner as any communist dictator, through repressing opposition to the Communist party and purging his opponents within the party. The political movements in China from 1950 – 1976, including “The Suppression of the Counter-Revolutionaries,” “The Great Leap Forward” and the “Cultural Revolution,” were all inspired and manipulated by Mao.

Mao’s infallibility did not last long after his death. His successor, Deng Xiaoping, while admitting that Mao had been one of the most influential men in Chinese history, criticized his mistakes in the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution. Deng Xiaoping then embarked on reforms of the Chinese economy which introduced capitalism and undid many of the changes wrought by Mao Zedong.

The Great Leap Forward began in 1958, after the success of China’s first five-year plan. The effort was to speed up industrialization at all costs. Poorly planned and poorly administered, the program collapsed. Chinese industrial production dropped as much as 50% between 1959 and 1962.

The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution was launched by Mao and his supporters in 1966. Their purpose was to eradicate any remaining bourgeois influence and to recapture the zeal of the revolution. Mao also wanted to weaken his political opponents within the party and to destroy entrenched privilege in the party bureaucracy. Groups of students and workers organized themselves into the Red Guards, targeting anyone of privilege or accomplishment, including intellectuals, bureaucrats, party officials, urban workers, teachers, doctors etc. Tens of millions of people died. There was bloody fighting among various Red Guard factions and between Maoists and anti-Maoists. The economy was disrupted and education halted.

Arthur Miller, the great American playwright, wrote The Crucible about the Salem Witchcraft trials and, by analogy, the Red Scares of the late 1940s and early 1950s. An interesting parallel between this period of Chinese history and those periods of U.S. history is provided by this comment in Miller’s autobiography:

In Shanghai in 1980, [“The Crucible”] served as a metaphor for life under Mao and the Cultural Revolution, decades when accusation and enforced guilt ruled China and all but destroyed the last signs of intelligent life. The writer Nien Cheng, who had spent six and a half years in solitary confinement and whose daughter was murdered by the Red Guards, could not believe that a non-Chinese had written the play. “Some of the interrogations,” she said, “were precisely the same ones used on us in the Cultural Revolution.” It was chilling to realize what had never occurred to me until she mentioned it — that the tyranny of teenagers was almost identical in both instances. Timebends, A Life by Arthur Miller, page 348.

1. See Discussion Questions for Use With any Film that is a Work of Fiction.

2. Do you think Fugui’s daughter and her husband were well suited because of their handicaps?

3. Show The Crucible and discuss that film. Then ask: What are the parallels between the Cultural Revolution and the Salem Witchcraft Trials?

Suggested Response:

In both cases, a rigid orthodoxy that might have served well in past times was threatened by changes in circumstances; the trials of the “witches” and the Cultural Revolution were ways to purge society of those thought to be disloyal, to reestablish the purity of society and to resist the change that proved inevitable.

4. During the late 1960s in the United States, there was a national “student strike” at many of the most prestigious universities in the country. This occurred in conjunction with the massive protests against the Vietnam War. There were many differences between the actions of the Red Guards in China and the student strikers in the United States, but there were a number of very interesting similarities. For example, for several years after the strike, academic standards fell dramatically. Both involved a loss of respect for major institutions in society. One of the differences was the fact that, in the U.S., the activities of the students were not supported by the highest political authority in the land. Talk to your parents or grandparents who were students during the late 1960s and make a list of these similarities and differences. Answer the question: was it mere coincidence that there were two similar youth movements in such different cultures with such different histories at roughly the same time?

Suggested Response:

TWM has no idea of what the answer to this question is. The coincidence is intriguing.

1. Why did Fugui refuse the bank account that was offered to him by his friend?

2. In what way did Fugui’s gambling addiction save his life?

3. What were the similarities and differences between Fugui’s gambling addiction and addition to a drug?

4. How does one deal with random death from accidents and carelessness, a risk for all of us?

Discussion Questions Relating to Ethical Issues will facilitate the use of this film to teach ethical principles and critical viewing. Additional questions are set out below.

(Treat others with respect; follow the Golden Rule; Be tolerant of differences; Use good manners, not bad language; Be considerate of the feelings of others; Don’t threaten, hit or hurt anyone; Deal peacefully with anger, insults, and disagreements)

1. What does this film tell you about the need for respect in society?

Books written for middle school and junior high school readers concerning life in China, include The Examination, by Malcolm Bosse, The Joy Luck Club by Amy Tan, China Under Communism by Michael Kort and China Past, China Future, by Alden Carten.

This Learning Guide was last updated on December 18, 2009.