THE RENAISSANCE:

The term “Renaissance” comes from the French word for “rebirth.” It refers to the flowering of art, literature, learning, and scientific inquiry that followed Europe’s rediscovery of classical Greek and Roman texts. These had fallen into disuse and had largely been forgotten during the Middle Ages. The Renaissance shifted the focus of Europe to secular pursuits. It set the stage for the scientific revolution, the Protestant Reformation, and the Age of Enlightenment.

The Renaissance began in the 1300s as a movement for educational reform in the city of Florence. The leaders of the Renaissance endorsed a “Humanist” curriculum which required students to read the secular classics of the ancient world. The goal was to enable students to learn the wisdom of the ancients directly and then to choose the right way to live. The new curriculum sought to create a well-rounded person and also included the writings of the Church Fathers, manners, dance, riding, and fencing. They held that full human development required participation in public affairs.

The focus on the direct reading of classical texts and the endorsement of Humanist education stimulated unprecedented inquiries into the nature of the Catholic Church and the authority of the papacy. The Renaissance was therefore an important precursor of the Protestant Reformation, which endorsed a direct reading of the Bible and rejected the authority of the Pope.

The scholars of the Renaissance were pious men who believed that classical learning would do more to enrich traditional religious beliefs than to undermine them. The Renaissance concept of Humanism did not mean a secular philosophy that denies an afterlife, as the term “humanism” is used today. Humanism did, however, deny to the church the right to rule civic matters. Humanist scholars were concerned with secular pursuits in addition to religious learning. These included secular art, philosophy, government, secular literature, and science, all based on the theories and discoveries of the ancients. Many areas of Renaissance scholarship, such as art, literature and philosophy, were characterized by a spirit of inquiry and experimentation. The Renaissance was a precursor of the scientific revolution and the age of Enlightenment.

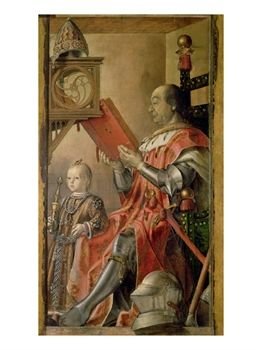

At first in Italy and then all over Europe, the aristocracy took up the humanist cause. While prowess at arms was the defining measure of aristocrats in the Middle Ages, during the Renaissance, aristocrats sought to demonstrate their superiority over the masses and over those aristocrats in competition with them not only by the power of their armed forces, but by embracing the new education and patronizing the arts. The wealth and power of a prince, king, pope, or archbishop would be established by the art that he could commission. The Humanist education of the aristocracy led to new standards of courtly behavior and commitment to elegance, taste, and refinement.

Most Italian princely courts had embraced Renaissance ideas by the mid-1400s. Aided by the invention of the printing press (1447), the Renaissance spread to most of Europe’s rulers in the 16th century. For example, King Henry VIII of England (1491 – 1547) was a poet, author, musician, composer, and sportsman, as well as a man who went through six different wives. He chose as Chancellor (and later beheaded) Sir Thomas More, one of the most remarkable men of the Renaissance, and the author of Utopia.

As the Renaissance spread to different parts of Europe, it developed characteristics particular to each country. However, humanist education covered the Greek and Roman classics wherever it was taught. The fact that all intellectual, middle, and upper class Europe was educated based on a similar humanist model meant that Europeans shared a fundamental cultural unity. Humanism brought a change in status because people began to be famous not only because they were kings or dukes but also because they were artists, sculptors, and authors. The Humanist valued participation in civic affairs, ability in the arts, and the combination of the contemplative and active life. The aristocratic courts, including the Vatican, competed for the best poets, painters, and sculptors who were expected to immortalize their patrons through works of art and architecture.

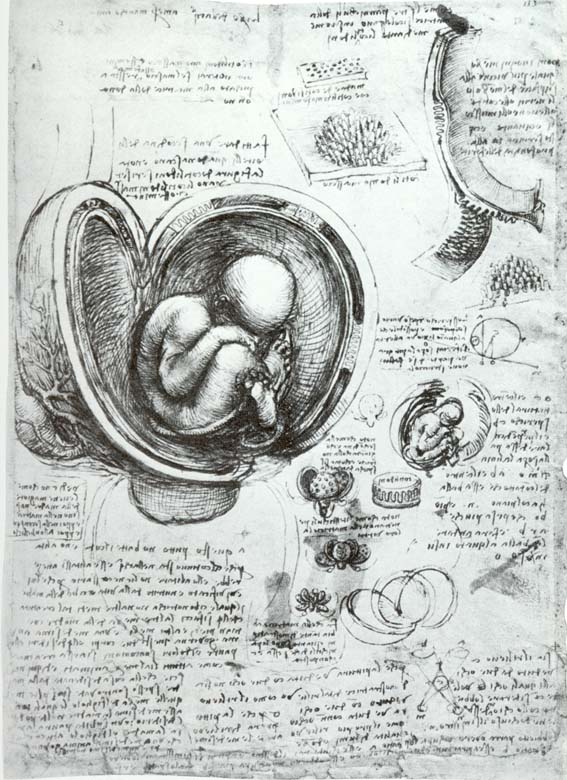

The emphasis on the secular works of the ancients led to the creation of purely secular works of art and literature in Europe. These arose alongside strong traditions of religious art and literature. Echoing the ancients’ respect for the human body, the Renaissance saw the first paintings of nude human forms since antiquity (Masaccio) and the emphasis on sculptures of idealized nude bodies (Donatello). Building techniques that had been used in antiquity but which had been lost were rediscovered. The Dome of the Florence Cathedral (1420 – 1426) was the first dome built in Italy since ancient times.

Thomas More wrote Utopia in 1515, coining the title (from outopos – Greek for “no place” and eutopos – “good place”). Utopia was an imaginary island ruled by scholars. Wealth, the nobility, private property, and money had been abolished. Cosmetics were scorned as were jewels and ostentatious clothing. Everyone worked the same number of hours and only priests and government officials were exempted from labor on a farm or in a trade. Goods were distributed equally and property was held in common. All the houses were of the same solid construction. All religions were tolerated. Euthanasia was encouraged and divorce permitted in special circumstances. Laws were brief and easy to understand. There were no lawyers. These concepts were revolutionary at the time.

The meaning of the word “utopia” has expanded to include any ideal place or society. It often has a futuristic connotation. The concept of utopia maintains a lively currency in the world today. Some scholars believe that Karl Marx, the father of communism, drew his emphasis on communal property and social equality from More’s writings. 1984 (George Orwell), Fahrenheit 451 (Ray Bradbury) and Brave New World (Aldous Huxley) are famous literary treatments of a dystopia (or anti-utopia): a nightmarish state or society. For more on Thomas More, see Learning Guide to “A Man For All Seasons”.

Sources: The Western Experience — Vol. I To the Eighteenth Century, 8th Edition by Mortimer Chambers et al., McGraw-Hill, 2003; Wikipedia articles on the Renaissance and the Renaissance in various countries; Articles on the Renaissance from Annenberg Media and Utopia by Thomas More.