THE WARS OF THE ROSES

During the “Wars of the Roses,” 1455 to 1485, two branches of the English royal family, the Lancasters and the Yorks, were fighting for the throne. The symbol of the Lancastrians was a red rose and that of the Yorkists, a white rose. Shakespeare’s play, Richard III concerns the last king produced by that conflict.

Edward IV, Richard of York’s older brother, was crowned King in 1461 after defeating the Lancastrian King Henry VI. Edward alienated his younger brother and heir apparent, George, Duke of Clarence, by favoring the relatives of his Queen, Elizabeth Woodville, and denying George a suitable marriage. Edward also quarreled with the powerful Duke of Warwick, in large part because he would not approve suitable marriages for Warwick’s daughters. Warwick and George rebelled and in 1470 drove Edward IV, accompanied by Richard, also called the Duke of Gloucester, from England. The Lancastrian, Henry VI, was then restored to the throne. But George found that he had poor prospects under Lancastrian rule because he was not heir to the throne and many of his estates had been seized from Lancastrians the decade before. With Lancastrians back in favor, there was a risk that these estates would be returned to their former owners. The next year Edward returned to England and, with Richard acting as mediator, was reconciled with George. Together, they defeated the Henry IV, the Duke of Warwick and the Lancastrians.

Richard was well rewarded for his support of the King in land and positions with the government. Soon George and Richard quarreled over lands and Richard’s desire to marry the Duke of Warwick’s younger daughter, Anne Neville. (George had married her older sister.) The King was required to intervene and impose a settlement, primarily to Richard’s advantage. George refused to fully comply with the terms of the settlement. The King charged him with treason in 1478 and George was executed privately in the Tower of London. Many think that the Queen and her relatives were the driving force behind the execution. Others blame the King. Richard may have had a hand in the death of his brother. He appears to have condoned it and he certainly benefitted from George’s downfall.

Edward IV’s major failing as a ruler was that he allowed the Woodvilles, the family of the queen, to amass power and wealth at the expense of other powerful forces in the land. The Queen was highly unpopular. Before he died, Edward tried to reconcile the parties and Shakespeare has transmuted that effort into the reconciliation scene in Richard III. The King died while his oldest son was still a young child and the parties struggled for control of the new child-King. The Woodvilles knew that because of their unpopularity, their only protection lay in him. Moreover, because of the untimely death of several men, the country did not have any respected and experienced men of power able to insist on an orderly dynastic succession.

Edward IV died in April of 1483. Richard, because of his loyalty to Edward IV and his leadership in suppressing a rebellion in Scotland was well regarded by large sections of the nobility. He was able to manipulate the deep divisions among the royalty and claim the kingship for himself. By the end of June, the strongest members of the Woodville family, except for the Queen, had been imprisoned or executed. Other opponents of Richard, such as Lord Hastings, had met the same fate. Edward’s son Henry, heir to the throne, had been imprisoned in the Tower along with his younger brother. Both children had been branded bastards and unfit to inherit the throne due to the alleged invalidity of the marriage of their parents. With the heirs of Edward IV eliminated from the line of succession, Richard became the “legitimate” heir to the throne. However, it was Richard’s own power and his alliance with members of the nobility that allowed him to ascend the throne.

Modern scholars do not agree with Tudor historians that Richard had been planning to seek the throne from before the death of Edward IV. They point out, for example, that the early moves in the struggle were made by Richard’s opponents, the Woodville family, which tried to seize the treasury and bring the young King to London at the head of an army they controlled. These actions would have had dire consequences for Richard had he not countered them.

Richard reigned for two years (1483 – 1485) before being defeated in battle by Henry Bosworth, later Henry VII, who established the Tudor line. England was ruled by Tudors for 118 years, until the death of Elizabeth I in 1603.

The play “Richard III” was written during the reign of the Tudor queen, Elizabeth I. It was therefore politically correct to denigrate Richard III, whose defeat had been necessary for the Tudor line to ascend the throne. Historians assert that Richard III was not a bad king. He promoted domestic reforms and furthered English interests in France. While Richard did usurp the throne, there is no hard evidence that he conspired in the murders of his brother Edward or of his young nephews. His evil has been exaggerated by Tudor historians. Tudor playwrights, including Shakespeare, turned him into the personification of evil.

NOTES ON THE PLAY

“Richard III” has many elements of the morality play, a medieval literary form. Morality plays have a character called “Vice” who is the embodiment of evil. But Shakespeare’s character, Richard III, is more than just a one-dimensional caricature of evil. Especially toward the end of the play, he is shown to be self-reflective and complicated. This makes his crimes all the more chilling.

Richard is not merely a villain to the characters in the play. He reaches out and manipulates the audience. In the first speech, he reveals himself as a plotter and an unfeeling criminal who has convinced one of his brothers (the King) to imprison his other brother, Edward. Later he will contrive to have the King order Edward’s execution. Richard tells us of his delight in his stratagems, enlists our appreciation for his craftiness and, with his tale of being born a cripple, appeals to our sympathy. He ridicules the King’s peaceful pursuits. In this way, he obtains our tolerance and even our admiration of his abilities as a conspirator. If we step back and look at what he is planning, we would be revolted. But it takes a while for us to realize that our sympathies have been enlisted for monstrous crimes.

Characters in the play who should be revolted by Richard’s actions react in a similar way. Lady Anne is perhaps the most obvious example. A victim of Richard’s evil, she allows herself to be seduced by his wordplay and audacity. Lord Hastings, too, is enlisted in Richard’s crimes; Richard rewards him by branding him a traitor and having him executed. Over the course of the play, it becomes apparent both to the audience and to England that Richard’s evil is deeper than a mere reaction to being born with a disability.

A Brief Introduction to Shakespeare’s Meter

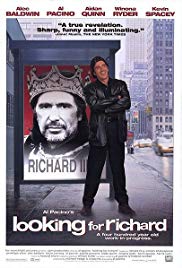

Richard’s speech at the beginning of the play is one of the most memorable in all of literature. Pacino spends a considerable amount of time on this speech. Read it out loud and discuss the meaning and the rhythm.

Now is the winter of our discontent

Made glorious summer by this sun of York;

And all the clouds that lour’d upon our house

In the deep bosom of the ocean buried.

Now are our brows bound with victorious wreaths;

Our bruised arms hung up for monuments;

Our stern alarums changed to merry meetings,

Our dreadful marches to delightful measures.

Grim-visaged war has smooth’d his wrinkled front;

And now, instead of mounting barbed steeds

To fright the souls of fearful adversaries,

He capers nimbly in a lady’s chamber

To the lascivious pleasing of a lute.

But I, that am not shaped for sportive tricks,

Nor made to court an amorous looking-glass

I, that am rudely stamp’d, and want love’s majesty

To strut before a wanton ambling nymph;

I, that am curtail’d of this fair proportion,

Cheated of feature by dissembling nature,

Deform’d, unfinish’d, sent before my time

Into this breathing world, scarce half made up,

And that so lamely and unfashionable

That dogs bark at me as I halt by them;

Why, I, in this weak and piping time of peace,

Have no delight to pass away the time,

Unless to spy my shadow in the sun

And descant on mine own deformity;

And therefore, since I cannot prove a lover,

To entertain these fair well-spoken days,

I am determined to prove a villain

And hate the idle pleasure of these days.

Plots have I laid, inductions dangerous,

By drunken prophecies, libels and dreams,

To set my brother Clarence and the king

In deadly hate the one against the other;

And if King Edward be as true and just

As I am subtle, false and treacherous,

This day should Clarence closely be mew’d up,

About a prophecy, which says that G

of Edward’s heirs the murderer shall be.

Dive, thoughts, down to my soul: here Clarence comes.

In poetry, language is used to create musical effects and to stress phrases or individual words. Meter in poetry forces each line to shape itself to the rhythmical pattern desired by the poet. While the meter of a poem is often a repeated rhythm, poets use variation to keep the language authentic and interesting. Shakespeare usually wrote his poems and plays in unrhymed iambic pentameter.

The term “foot” refers to the groups of syllables in a line of poetry. An “iamb” is a foot the contains two syllables in which the stress is on the second syllable in each pair. For example: “upon” has the stress on the second syllable, whereas “open” has the stress on the first. “Upon” is an iamb. Pentameter is a line of verse consisting of five metrical feet. Thus, Shakespeare’s dominant meter, “iambic pentameter”, has five iambs in each line. For links to websites about iambic pentameter, Click here.

Good poets rarely adhere strictly to the dominant rhythm because variations in rhythm permit them to stress certain words or phrases. In addition, a poem may become “sing-songy” if kept in a strict rhythm. Variations are supplied within the overall metrical framework through such devices as variation in stress and in the length of vowel sounds, repetition of words or syllables, and the caesura, a pause in the flow of a line of poetry. Variation is also provided by exceptions to the normal rhythmic pattern. The names given to poetic feet that are different than the iamb include the trochee, in which the stress is on the first syllable (“open”), and the spondee in which the stress is on both syllables. A dactyl is a three-syllable foot consisting of a stressed syllable followed by two unstressed syllables.

Shakespeare’s audience was accustomed to iambic pentameter in the speeches of kings, princes and aristocrats. An example is King Edward’s lament about ordering the execution of his brother, George, Duke of Clarence. In Act II, Scene One, King Edward is asked by the Earl of Derby to make a decision in the matter of the Earl’s servant who had killed one of George’s servants. (Syllables with emphasis are in bold and feet with variations from strict iambic pentameter are underlined. Note that scansion of poetry is a matter of interpretation; different actors may give various syllables different stresses.)

Have I/ a tongue/ to doom/ my bro/ther’s death,

And shall/ that tongue/ give par/don to/ a slave?

My bro/ther kill’d/ no man/ — his fault/ was thought,

And yet/ his pun/ishment/ was bit/ter death.

Who sued/ to me/ for him/? Who, in/ my wrath,

Kneel’d at/ my feet,/ and bid/ me be/ advise’d

Who spoke/ of bro/therhood/? Who spoke/ of love?

Who told/ me how/ the poor/ soul did/ forsake

The might/y War/wick and/ did fight/ for me?

Who told/ me, in/ the field/ at Tewks/ bury

When Ox/ford had/ me down/, he res/cued me

And said/ ‘Dear Bro/ther, live/, and be/ a king‘? …

Within the iambic pentameter framework, there are many phonetic events occurring in this passage. Shakespeare judiciously uses long and short vowel sounds to vary the rhythm and support meaning. The repetition of the word “who” provides emphasis. “Tongue,” used twice in the space of two lines, makes the listener/reader feel the tongue in his or her own mouth and sense the power of words spoken by a monarch. You can hear the regret, almost the sobs, in the many caesurae in this passage. And still, the iambic pentameter rhythm is strong. Of 120 feet, only six appear to vary the iambic pattern.

The phrase “poor soul” sets up a fascinating metrical analysis. It has a spondee feeling (a foot of two stressed syllables). This is because, although the words belong to two different metrical feet, they are part of one term. We have it as an iamb followed by a trochee (stress on the first syllable) or it could be part of a unique unnamed foot with four feet and two stressed syllables in the middle, a kind of monster spondee. An argument can also be made that “did” is also stressed. It is certainly more stressed than the “for” in forsake. People will differ on the analysis of the meter in this line, but most will agree that the rhythm and meaning join to make beautiful lines of poetry.

The analysis of words as either stressed or unstressed is over simplistic and misses many of the words which receive a partial stress. These are usually classed as unstressed syllables. Examples are: the “no” in “no man”, the “his” in “his fault”, the “who” in lines 5, 7, 8 and 10, and the “he” in “he rescued me.”

Iambic verse is still used today. Robert Frost’s poem “Stopping By Woods on a Snowy Evening” is a beautiful example of iambic verse, this time with four feet per line (iambic tetrameter).

Whose woods/ these are/ I think/ I know,

His house/ is in/ the vil/lage though.

He will/ not see/ me stop/ping here,

To watch/ his woods/ fill up/ with snow.

My lit/tle horse/ must think/ it queer/,

To stop/ without/ a farm/house near,

Between/ the woods/ and fro/zen lake,

The dark/est eve/ning of/ the year.

He gives/ his harn/ess bells/ a shake,

To ask/ if there/ is some/ mistake.

The on/ly o/ther sound’s/ the sweep,

Of ea/sy wind/ and down/y flake.

The woods/ are love/ly, dark/ and deep,

But I/ have prom/ises/ to keep,

And miles/ to go/ before/ I sleep,

And miles/ to go/ before/ I sleep.

Here again, the poem is dominated by iambs, with only one out of 16 lines containing a foot that is not iambic.

Frost uses variations in rhythm that don’t actually break out of the iambic pattern to keep the sound interesting and to highlight concepts. The first line stresses and repeats the word “I” despite the fact that it is the unstressed syllable in both iambic feet in which it appears. The same device is used in the gentle ending of the last two lines. In the reiterated phrase “before I sleep” the word “I” has a stress almost equal to its iambic partner, the word “sleep.” This poem is focused on the individual, his reaction to a beautiful scene in nature, the desire for reflection, the pull of obligation, the march of life toward mortality, etc. The repeated use and stress of the word “I” aids this focus. Another example of variation in rhythm is found in the 11th line which uses three long sounds (“only,” “other,” “sound’s”) to slow us down and make us listen for the “sweep,/ Of easy wind and downy flake.”

The one variation on the iambic meter is in the second line of the fourth quatrain in which none of the syllables in the foot “ises” are stressed. However, this serves meaning by highlighting the next foot, the words “to keep”; helping to bring us from the world of contemplation of nature back to the world of practicality with its “obligations.”

The opening speech of “Richard III” is an excellent example of how Shakespeare uses rhythm in the service of meaning and beauty. Note that the word “glorious” should be pronounced as having only two syllables and “alarums” was pronounced in Shakespeare’s time like the modern “alarms.”

Now is/ the win/ ter of/ our dis/content

Made glor/ious sum/mer by/ this sun/ of York;

And all/ the clouds/ that lour’d/ upon/ our house

In the/ deep bos/om of/ the oc/ean buried.

Now are/ our brows/ bound with/ victor/ious wreaths;

Our bruis/ed arms/ hung up/ for mon/uments;

Our stern/ alarums/ changed to/ merry/ meetings,

Our dread/ful march/es to/ delight/ful measures….

Stressing the first syllable in a line, a trochee, to give it added power was a standard variation in Elizabethan blank verse. Thus the first line of the play and the first line of the second sentence receive emphasis in this manner. The word “Now” captures and commands the audience’s attention, as Richard will soon ensnare the other characters in his schemes and command them.

The next line which refers to the “glorious” summer emphasizes both the sound of the word and the importance of the achievements of the House of York. The fourth line which stresses the finality of the Yorkist victory is irregular, containing eleven syllables rather than ten. Elizabethan poets often added a single unstressed syllable at the end of a line of blank verse. The reassuring alliteration of the “b” in “bosom” and “buried” adds to this effect. The last syllable of buried falls off and carries the sense of something sinking into the ocean. In this way the meter and sound are illustrative of both the security brought by Edward’s rule and the finality of that victory.

The fifth line, in addition to beginning with the stressed and repeated “now” contains two important words which begin with the consonant “b” (“brows” and “bound”). This repeats the “b” sounds of the fourth line. The irregular stresses in the feet in this and the next three lines, the words “bound”, “hung” and “changed”, are a drumbeat of increasing excitement which reaches its height in the seventh line in which three of the five feet have the stress on the first syllable.

This analysis shows how two different poets, centuries apart, use rhythm to serve the music and meaning of poetry.

RICHARD III AS A MACHIAVELLIAN

The character of Richard III in this play owes much to The Prince by Machiavelli (1469 – 1527). Published in 1532, five years after Machiavelli’s death, The Prince has become the classic description of how to obtain and maintain power by calculated, sometimes ruthless, amoral actions. It is based on the view that a ruler is exempt from the normal strictures of ethical conduct and should concern himself only with maintaining control over his subjects. Machiavelli was a diplomat and public servant for the Republic of Venice, as well as a historian. To find the means by which political power could be obtained, Machiavelli studied the practices of the rulers in Europe during his lifetime and in ancient days. The term “Machiavellian” has come to refer to the principles of power politics, expediency, deceit and cunning.

LADY ANNE

The most dated episode in the play is the seduction of Lady Anne. In order to appreciate this scene one must understand not only Richard’s evil charisma, but also relations between men and women in Shakespeare’s time. Much of this has changed and it was changing even in the sixteenth century. Especially for aristocrats and royalty, the concept that people should marry for love was only just beginning to take hold. Several of Shakespeare’s plays deal with the conflicts between love and the obligations of a child to marry the spouse selected by the family. See, for example, Romeo and Juliet. Marriages were matters of power and the aggregation of property for the family. The dependence of women on their men was complete. As the Queen said, “The loss of such a lord includes all harm” (Act I, Scene III). After her husband was killed, Lady Anne faced a bleak future until Richard took notice of her.